Everything You Wanted to Know About Barbican Architecture

Few people know their way around better than our assistant curator in architecture and design, Jon Astbury, who’s here with some of his favourite facts and photos to inspire your next visit.

Was the Barbican deliberately designed to be hard to navigate?

Not quite. The Barbican’s nature as an elevated island is due in part to the scrapped Pedways scheme, an initiative that once planned to cover the entire City with an incredible network of raised walkways for the Barbican to plug into. With the Barbican’s empty site this was easy to create, but it proved too difficult to retrofit existing buildings with Pedway connections. Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the architects who designed the Barbican, claimed to be designing not just buildings but an entire neighbourhood, with a multitude of entrances and exits. If you have a thorough explore of the estate, you’ll discover plenty of routes through, inside and out. Many of these routes have been changed over the years. The entrance to the Art Gallery was once via the Highwalk, and the main entrance to the Centre was via the Lakeside. These were later reconfigured – while you can still access the centre via the Lakeside, a new main entrance was created on Silk Street to make it far more accessible.

'If you have a thorough explore of the estate, you’ll discover plenty of routes through, inside and out'

Was the Barbican conservatory really built to hide the Theatre fly tower?

Yes - one of the main drivers for the Conservatory’s location was to conceal the concrete stump of the fly tower used by the Theatre below, which was considered to be unattractive for the residents in the neighbouring Cromwell Tower. In early plans, this conservatory space was envisioned inside a giant glass pyramid on the lake.

'In early plans, this conservatory space was envisioned inside a giant glass pyramid on the lake'

How was there such a large site in the middle of the City on which to build the Barbican Estate?

Projects at the scale of the Barbican in such a central location happen so rarely for the simple reason of space. Some more extreme Modern architects thought this space should be created by wiping away old cities - the Swiss Architect Le Corbusier, for example, had plans to entirely rebuild Paris. But for the City and the Barbican’s site, the Blitz had already wiped away most of the area once home to London’s cloth trade. So extensive was the destruction that by 1951 just 48 people were registered as living in the Cripplegate Ward.

Was the Barbican always meant to be made entirely of concrete?

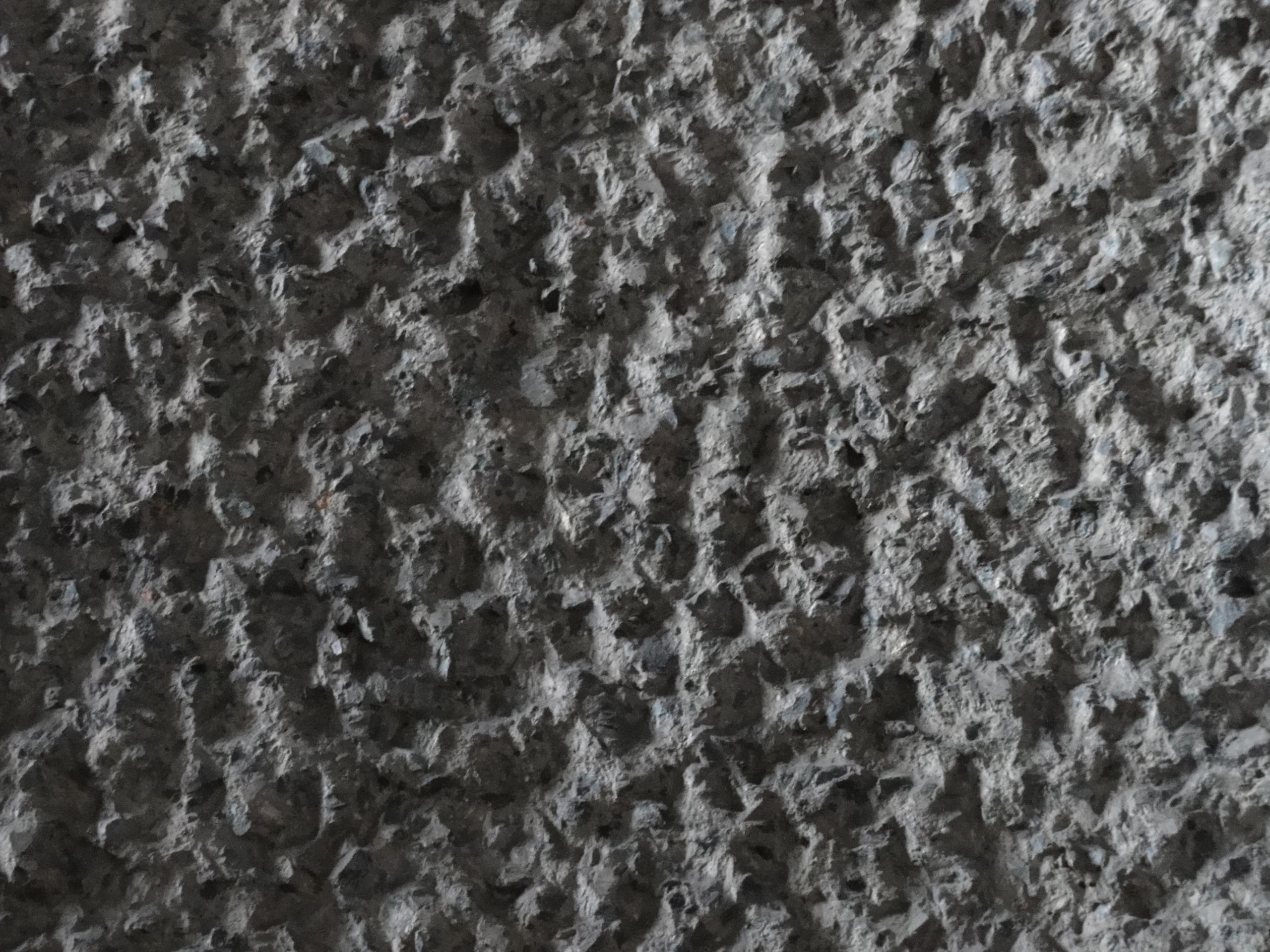

Throughout the various phases of its planning, the Barbican’s appearance went through many iterations that would’ve completely altered its appearance from the rough concrete finish that it’s now famous for.

Originally, Chamberlin, Powell and Bon intended the Barbican to look similar to their designs for the neighbouring Golden Lane Estate, with coloured panels and more delicate detailing. In a 1959 report, the architects outlined plans for the terrace blocks to be covered with white marble, the towers to be coated with highly polished concrete, and columns to be finished in smooth, coloured concrete. It was even proposed that the balconies be surfaced with mosaic tiles.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this rather lavish and costly selection of materials was turned down by the City of London, resulting in the cheaper - although incredibly labour intensive - hammered concrete finish we know and love.

'The architects outlined plans for the terrace blocks to be covered with white marble...'

Was the estate originally built as council housing?

Not in the conventional sense, although the Barbican’s flats were originally leased by the City of London Corporation. Almost all of them became privately-owned when Right to Buy was introduced in 1980. While the neighbouring Golden Lane Estate, also designed by Barbican Architects Chamberlin Powell and Bon, was conceived as council housing, the Barbican was always intended for a different audience, described by the architects as “… young professionals, likely to have a taste for Mediterranean holidays, French food and Scandinavian design.”

The estate was a means of attracting them back into what had become a rather deserted City after the war - and its design was intended as a large part of this draw.

A home for...

'Young professionals, likely to have a taste for Mediterranean holidays, French food and Scandinavian design.'

Why are there no sculptures in the Sculpture Court?

Originally, the Art Gallery opened out onto the sculpture court through a set of doors that are now on the gallery’s side, allowing for movement between indoor and outdoor exhibitions.

The sculpture court’s current condition as a green oasis with curiously few sculptures is mainly due to two factors. When the gallery was upgraded to meet the modern, climate-controlled standards allowing it to borrow and display artworks, the connection to the outside had to be closed. The surrounding Frobisher Crescent, while originally built as offices, was also partially converted into residential flats, with the new planting and decking providing an outlook for residents. There may be no sculptures, but the space is still occasionally used for outdoor artworks and performances.

'Originally, the Art Gallery opened out onto the sculpture court through a set of doors that are now on the gallery’s side'

Who designed the signage, and why are there little castles everywhere?

It was important to the architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon that the large estate and centre were tied together with visual motifs. Text played an important part in this, and they enlisted Herbert Spencer to design the font and signage around the estate.

The little castle that appears around the estate is a depiction of the Roman watchtower or ‘Barbican’ on the site that inspired the area’s name and design. It was used as the original logo for the estate and is still used in some places today.

'The little castle that appears around the estate is a depiction of the Roman watchtower or ‘Barbican’'

Where do the estate’s blocks take their names from?

The estate is made up of three tower blocks, thirteen terrace blocks, two mews, and two blocks of townhouses. The towers sport perhaps the most well-known names, with Shakespeare and Cromwell Towers named after William and Oliver respectively. Many others are named after notable figures who lived in or close to Cripplegate Ward, including Robinson Crusoe author Daniel Defoe (Defoe House), author of The Pilgrim’s Progress John Bunyan (Bunyan Court) and the poet and writer Nicholas Breton (Breton House).

Was it always the plan to have an arts centre within the estate?

The Arts Centre was always planned as one of the many amenities on the doorstep of Barbican residents, along with shops, restaurants, pubs, schools and even a church in the form of the existing St Giles. How much did it cost? The housing estate, which was completed in 1974 cost £156m, while the arts centre (opened in 1982) cost £161m. That’s equivalent of about £500m today.

'Three tower blocks, thirteen terrace blocks, two mews, and two blocks of townhouses (and an arts centre)'

Why do you dye the water in the lakes?

Because the water is very shallow, if it wasn’t dyed, you’d be able to see reflections of the grey buildings surrounding it, which could give away the illusion of depth. And if you were wondering why you can’t swim in the lake, it’s for the same reason – it’s just too shallow. That’s because the Circle Line is directly underneath it, so it couldn’t be dug any deeper.

'If you were wondering why you can’t swim in the lake, it’s for the same reason – it’s just too shallow'

Is the Barbican haunted?

We’ll let you be the judge of this, but several Barbican staff members working late shifts have reported strange sightings and goings-on, with some refusing to work on Level -2 after sightings of ghostly Centurions lingering where the Roman fort once stood.

As well as its Roman foundations, the site of the Barbican is also close to sites used as plague pits during the Black Death.

Guide to Brutalism

We break down some of the history behind the architectural style, Brutalism.

Why is it called Brutalism?

The word came from Swiss Modernist Le Corbusier’s description of the material used for his housing development in Marseille - ‘beton brut’, meaning raw concrete – and was then popularised by the critic Reyner Banham.

But why would a building want to look ‘brutal’ on purpose?

Brutalism’s core idea was one of honesty, that a building should not hide what it is made of or how it is put together.

Brutalism’s followers saw beauty in this honesty. For some, it even became a moral or philosophical issue.

Just as we may not enjoy people being brutally honest with us, this revealing of a building’s ‘truth’ was not to everybody’s tastes, and it has remained a polarising style ever since.

Why were Brutalists obsessed with concrete?

Brutalism does not require concrete - some of the early examples were built using wood and steel - but the style has become synonymous with concrete due to its wide availability and cheapness in the 60s and 70s.

But the Barbican still has its ornamental, shapely elements. Does this still count as Brutalism?

The Barbican’s architects, Chamberlin Powell and Bon, never explicitly called themselves Brutalists. They drew inspiration from a large range of styles, and the Barbican does contain some contradictions. It was once planned to be far more decorative, covered with marble, colour and mosaic.

Are Brutalist buildings still being designed today?

While Brutalism doesn’t have the avid proponents it once had, many contemporary structures would be grouped into its style.

Explore the Barbican Archive

Want to learn more about the Barbican? From the history and construction of the Barbican, to our programme and design, we are developing an archive to tell the story of the Barbican and Guildhall School of Music & Drama ahead of our 40th anniversary in 2022.