Carolee Schneemann

Find out more about the radical artist and her fascinating life

Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics

Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019) was a trailblazer, whose experimental work defies easy categorisation. Across six decades, from the late 1950s onwards, she experimented with paint, found objects, her own body, text, performance, film, and multimedia installations. She explored her own sexual expression, the objectification and oppression of women, human-animal relationships, war, cancer, mortality, and more. For Schneemann, the personal was political, and she boldly addressed persistent taboos in the world around her.

Untitled (Blue Self-portrait), 1959. Graphite, coloured pencil and pastel on paper. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Untitled (Blue Self-portrait), 1959. Graphite, coloured pencil and pastel on paper. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Beginnings

Schneemann was born in Fox Chase, Pennsylvania to a rural physician father and a homemaker mother. As a child, she assisted with treating patients, recalling that, ‘people would come to the house with bloody limbs in their arms […] I had a Gray’s Anatomy to look at, and it gave me a peculiar sense, an inside/out visual vocabulary.’

From her earliest drawings made aged four, she was preoccupied with an instinct for collage and a fascination for how an image could exist not just in space but across time: ‘I became obsessed with the image as something fractured in time, so that each page was treated as a moment and it would take five or ten pages before the image came together.’ This obsession expanded to her Life Books, a decades-long project which collated the ephemera of her life — photographs of herself and loved ones, notes, phone numbers, receipts, exhibition reviews, and flyers — into sketchbooks. She saved everything, including childhood drawings, one later becoming the cover of her artist’s book Cézanne, She Was A Great Painter (1975).

In 1952, the same year that avant-garde composer John Cage premiered his ground-breaking piece 4’33”, Schneemann enrolled at Bard College, in upstate New York, on a full scholarship. Two years later, she was suspended for ‘moral turpitude’. Schneemann suspected this was for painting her own naked body due to the lack of life models at the college. In Untitled (Self-Portrait with Kitch) (1957), Schneemann depicts herself nude with a third arm blurred as if in the process of sketching, life model and artist in one.

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Kitch), 10 August 1957. Coloured pencil and pastel on paper. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Kitch), 10 August 1957. Coloured pencil and pastel on paper. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann, c. October 1939. From Life Book 1, c. 1920s–50s. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann, c. October 1939. From Life Book 1, c. 1920s–50s. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Life Book 2, c.1960s–70s. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Life Book 2, c.1960s–70s. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Life Book 2, c.1960s – 70s. Sketchbook, pp. 69 – 70, 42 x 65 cm. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Life Book 2, c.1960s – 70s. Sketchbook, pp. 69 – 70, 42 x 65 cm. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Breaking the Frame

Personae: J.T. and Three Kitchs, 1957. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee SchneemannPersonae: J.T. and Three Kitchs, 1957 Oil on canvas 80.6 x 123.2 cm. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Schneemann transferred her studies to Columbia University. While there, she met James Tenney, a music student at The Juilliard School. Tenney and Schneemann became lovers, entering a deeply equitable relationship of collaboration and artistic exchange. Her opening words to Tenney — ‘I’m a painter and I treat space as if it’s time’ — are exemplified in her portrait of him, Personae: J.T. and Three Kitchs (1957). Tenney, reclining on a sofa, is surrounded by multiples of Kitch the cat who appears as a fizzing, flying bundle of loose brushstrokes. The work nods to Schneemann’s desire to make paintings which were events. It also subtly inverts presupposed gender dynamics; she later commented that the work caused a stir as its depiction of Tenney, in repose with his genitals on show, was considered emasculating by peers.

Kitch, the other star of the painting, was a crucial third presence in Schneemann and Tenney’s domestic arrangement. Throughout her life, the cats which lived with Schneemann were her closest companions. She refused to call them by possessive pronouns; Kitch, Cluny, Vesper, Treasure, and La Niña were cohabitors, friends, and artistic collaborators.

‘Kitch-frighty example of Kitchhood: fearsome warringer, Sphinx of the bent knee and curly lap, conqueress of hairy summits, naily peaks, and pitfall valleys. Guardian of the sleepers, gong and scratch of the morning. Moth snatcher, egg lapper, cat napper, wood tapper, eyed latcher, neat crapper. Fluff ball. Din and Gammon. Furr purr fuss buzz.’

Carolee Schneemann and Kitch, 1959. From Life Book 2, 1960s–70s. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann and Kitch, 1959. From Life Book 2, 1960s–70s. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Aria Duetto (Cantata No. 78): Yellow Ladies, 1957. Oil on canvas. Collection of KAWS. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Aria Duetto (Cantata No. 78): Yellow Ladies, 1957. Oil on canvas. Collection of KAWS. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Colorado House, 1962. Wood, stretchers, wire, fur, strips of painted canvas, bottles, broom handle, glass shards, flag, photograph and plywood base. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Colorado House, 1962. Wood, stretchers, wire, fur, strips of painted canvas, bottles, broom handle, glass shards, flag, photograph and plywood base. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann, James Tenney and Kitch, 1957. From Life Book 1, c. 1920s–50s. Sketchbook, p. 89. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann, James Tenney and Kitch, 1957. From Life Book 1, c. 1920s–50s. Sketchbook, p. 89. Carolee Schneemann Papers, Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries (M1892). © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann Infinity Kisses (I), 1981–87 Xerox ink on linen. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Accessions Committee Fund purchase: gift of Collectors' Forum, Christine and Pierre Lamond, Modern Art Council, and Norah and Norman Stone. Photo: Ben Blackwell. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Carolee Schneemann Infinity Kisses (I), 1981–87 Xerox ink on linen. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Accessions Committee Fund purchase: gift of Collectors' Forum, Christine and Pierre Lamond, Modern Art Council, and Norah and Norman Stone. Photo: Ben Blackwell. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

The Downtown Scene

After an interlude spent studying in Illinois and living in New Jersey, Schneemann returned in 1961 to Manhattan, New York and became enmeshed in the art scene there. Amongst throwing huge parties for crowds of ‘100 sweating rocking streaming rapturous stamping flying artists’, participating in Claes Oldenburg’s happening Store Days I (1962), and frequenting the studios of Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, Schneemann was creating works which pushed the boundaries of painting ever further. She salvaged tin cans, magazine cuttings, and even Tenney’s underpants, incorporating them into the pictorial surface.

Like her contemporaries, Schneemann merged detritus and art, so-called ‘low’ and ‘high’ culture, to convey the rushing immediacy of her surroundings. However, in an environment dominated by men with larger-than-life personalities, she took things a step further: ‘The one thing the guys haven't done at this time in 1962 is to motorize, to take the energy of the pictorial surface into actual literal movement.’ She had moved toward animation with Pin Wheel in 1957, which could be spun by the viewer, but with Fur Wheel was a spinning, clanking assemblage made using scraps of fur sourced from her New York loft, a former furrier’s studio. As well as embodying her concept of ‘kinetic painting’, the fur was ‘primitive, dark, mysterious’, an animistic and feminine object.

In the same year she made Fur Wheel, Schneemann became an inaugurating member of Judson Dance Theater, which brought together choreographers, dancers, musicians, composers, visual artists, and filmmakers (among them John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and dancer Yvonne Rainer) to realise experimental performances. Taking inspiration from gestures and materials from everyday life, these events which Schneemann called ‘kinetic theatre’ were highly collaborative works. Her work with group performance reached its pinnacle in Meat Joy (1964) which she described as ‘flesh jubilation’, the performers’ bodies tangling together with raw fish, chickens, paper, hot dogs, and paint.

‘I did want to make it clear that I was the first painter to choreograph for the Judson Dancers; that my contribution to performance art is based on an extended painters' vocabulary of forms in motion.’

Meat Joy, 16 and 18 November 1964 Judson Dance Theater, Judson Memorial Church, New York. Photograph by Al Giese. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo © Al Giese / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022.

Meat Joy, 16 and 18 November 1964 Judson Dance Theater, Judson Memorial Church, New York. Photograph by Al Giese. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo © Al Giese / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022.

Tenebration, 1961 Oil paint on canvas, paper, wood, fabric, metal pins, wire mesh and gelatin silver prints (Wanda Landowska, Johannes Brahms and Ludwig van Beethoven) mounted on wooden board. Private Collection, London. Photograph by JSP Art Photography. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Tenebration, 1961 Oil paint on canvas, paper, wood, fabric, metal pins, wire mesh and gelatin silver prints (Wanda Landowska, Johannes Brahms and Ludwig van Beethoven) mounted on wooden board. Private Collection, London. Photograph by JSP Art Photography. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Fur Wheel, 1962 Oil paint, fur, tin cans, mirrors and glass construction on lamp shade base, mounted on turning wheel, 48.5 × 48.5 × 29.3 cm Generali Foundation Collection—Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg. © Generali Foundation, Photo:Rainer Iglar. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Fur Wheel, 1962 Oil paint, fur, tin cans, mirrors and glass construction on lamp shade base, mounted on turning wheel, 48.5 × 48.5 × 29.3 cm Generali Foundation Collection—Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg. © Generali Foundation, Photo:Rainer Iglar. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Newspaper Event, 1963. Photograph by Robert McElroy. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © 2022 Estate of Robert R. McElroy / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Newspaper Event, 1963. Photograph by Robert McElroy. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © 2022 Estate of Robert R. McElroy / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Meat Joy, 16 and 18 November 1964. Judson Dance Theater, Judson Memorial Church, New York. Photograph by Al Giese. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo © Al Giese / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022.

Meat Joy, 16 and 18 November 1964. Judson Dance Theater, Judson Memorial Church, New York. Photograph by Al Giese. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo © Al Giese / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022.

Transformative Actions

Meanwhile in her studio, Schneemann staged a solo performance: Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera (1962). She harnessed the power of photographic documentation, as with all her performances, in order to ask: ‘Can I be both an image and an image maker?’ Posing amongst her own works, transformed by body paint, covered in serpents, she asserted herself as both subject and artist and, in the process, became almost mythological, calling on ancient iconographies of divine femininity.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, December 1963. Gelatin silver print, printed 2005. Photograph by Erró. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Erró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, December 1963. Gelatin silver print, printed 2005. Photograph by Erró. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Erró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

The urgency of Schneemann’s question was made clear by her own participation in Robert Morris’s 1964 performance, Site, in which she portrayed the character of Edouard Manet’s Olympia. Later, she would comment: ‘I saw only deformation, distortion, projection, imposition and cutting away what my real occupancy of the space was about. Here we were again, and of course I was historicized and immobilized.’

Schneemann’s determination to claim agency and celebrate bodily autonomy underpinned much of her work. In Fuses (1964–67), an experimental film documenting her erotic relationship with Tenney, Schneemann foregrounded her own sexual pleasure.

The backdrop for this work was Schneemann’s Huguenot house in New Paltz, a few hours north of New York City, which she would inhabit for the rest of her life. To this day, it remains a repository for her extensive self-archiving efforts.

Carolee Schneemann and Anthony McCall at 437 Springtown Road, New Paltz, New York, 1973. Photograph by Anthony McCall. Photo © Anthony McCall.

Carolee Schneemann and Anthony McCall at 437 Springtown Road, New Paltz, New York, 1973. Photograph by Anthony McCall. Photo © Anthony McCall.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, December 1963. Gelatin silver print, printed 2005. Photograph by Erró. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Erró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, December 1963. Gelatin silver print, printed 2005. Photograph by Erró. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Erró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, December 1963. Gelatin silver print, printed 2005. Photograph by Erró. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Erró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022.

Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, December 1963. Gelatin silver print, printed 2005. Photograph by Erró. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Erró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Film stills from Fuses, 1964–67. 16 mm film transferred to HD video, colour, silent, 29:51 min. Original film burned with fire and acid, painted and collaged. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Feminism and missing precedents

Schneemann’scommitment to championing women’s intellect and creativity was lifelong. In the back pages of her copy of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), she pencilled a long list of women’s names: writers, poets, artists, saints, and monarchs. Her furious determination in retrieving an overlooked history expanded to her research of feminine deities and symbols associated with fertility, knowledge which she referred to as ‘vulvic space’.

Interior Scroll, 1975. Women Artists Here and Now, East Hampton, NY. Photograph by Anthony McCall. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Anthony McCall.

Interior Scroll, 1975. Women Artists Here and Now, East Hampton, NY. Photograph by Anthony McCall. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: © Anthony McCall.

Schneemann contested the idea that the mind and body are divided. Her art concerned knowledge received ‘from and in the body’, a concept literalised in her work Interior Scroll (1975–77). The solo performance began with a series of exaggerated life model poses, which recalled the circumstances of her expulsion from Bard College and the ever present-question of being both image and image-maker. She then unwound a tightly-folded scroll from her vagina and read from its text. In a 1977 performance protesting the sexist title – The Erotic Woman – of a film festival she’d been invited to participate in, this text relayed a conversation with a structuralist filmmaker. The filmmaker criticised her films for their ‘personal clutter’, ‘persistence of feelings’, and ‘painterly mess’. Schneemann’s performance highlighted the sharp contrast between the social construction of men’s intellect as rational and of women’s bodies as abject and disorderly.

Sexual Parameters Chart II, 1969–75 Pen on monoprint (xerox). Lonti Ebers, New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Sexual Parameters Chart II, 1969–75 Pen on monoprint (xerox). Lonti Ebers, New York. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Cézanne, She Was a Great Painter (Unbroken Words to Women – Sexuality Creativity Language Art Istory), 1975. Artist’s book. Printed in three editions: January 1975, June 1975 and 1976 Published by Tresspuss Press, New Paltz, NY. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Cézanne, She Was a Great Painter (Unbroken Words to Women – Sexuality Creativity Language Art Istory), 1975. Artist’s book. Printed in three editions: January 1975, June 1975 and 1976 Published by Tresspuss Press, New Paltz, NY. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Activism

Schneemann’s awareness of her body’s position in society was coupled with the feeling of her own inextricability from global politics. One of her earliest films, Viet-Flakes (1962–67), protests the brutality of American military intervention in the Vietnam War. With a 35mm camera, she zoomed in and out on ‘Vietnam atrocity images’ which she had collected from newspapers and magazines. Viet-Flakes confronts the viewer with the devastating consequences of war. In it, and in the political film works that followed, Schneemann sought to combat the way in which Western media reportage allowed its audience to feel detached from global injustices.

As with her paintings, Schneemann’s films fracture time. Both audio and moving image are jumping, juddering, and disjointed. In her politically activist films, this effect takes on an especially jarring quality. Devour, a film installation from 2003–04, juxtaposes three seconds of footage from Schneemann’s personal life — an intimate kiss, a cat meowing, a morning shave — with three seconds of film appropriated from conflict zones in the Balkans, Caribbean, and Middle East. By bringing the pleasurable everyday into close contact with military violence, Schneemann suggests we are all implicated in the social power structures which create war.

‘We never stopped blowing up these other people and our own selves and lying about it. And towards the end of the ’60s, our major political figures had been assassinated.’

The Lebanon Series, 1983. Artist’s book, photocopied paper. Published on the occasion of Carolee Schneemann: New work: Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints, Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York, 10 September–8 October 1983. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

The Lebanon Series, 1983. Artist’s book, photocopied paper. Published on the occasion of Carolee Schneemann: New work: Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints, Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York, 10 September–8 October 1983. © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

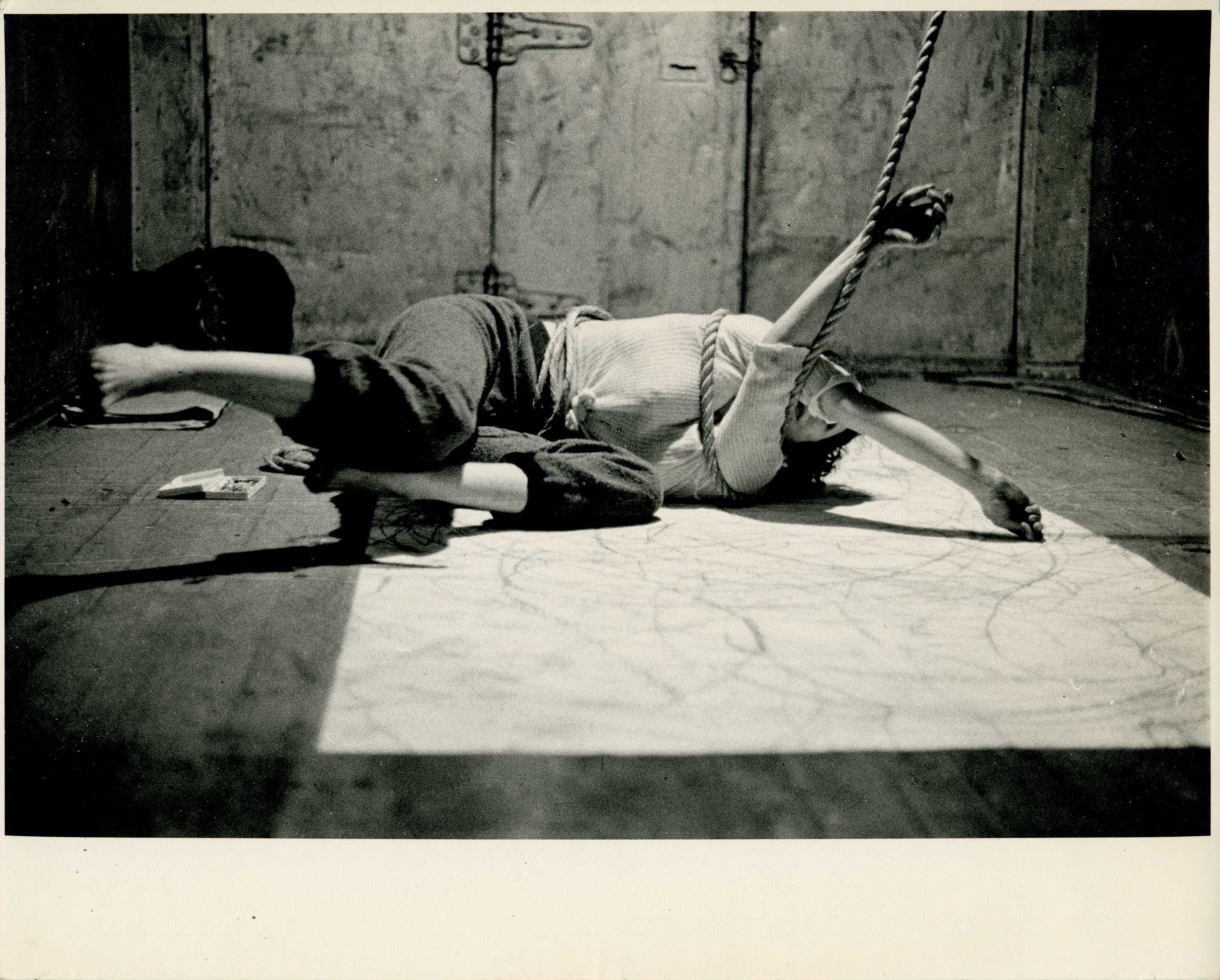

main image credit: Snows, 1967. Photograph by Charlotte Victoria. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Mortal Coils

In both her life and her art, Schneemann was deeply compassionate. In the mid-1990s, she lost several close friends including filmmaker Derek Jarman and artist Hannah Wilke to causes such as AIDS-related illness and cancer. Mortal Coils (1994–95), an installation which brings together projected portraits with winding ropes and newspaper obituaries, was her response: both a tribute to her loved ones and a poignant reflection on grief itself.

In 1995, Schneemann herself was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and breast cancer. She would battle with cancer for the last two decades of her life. Schneemann resisted clinical advice to proceed with a mastectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy, concerned that they would strip away the forms of erotic, bodily pleasure so central to her life, as well as her ability to work. Instead, she sought alternative treatment. She stated: ‘I am alive because a Pollock-Krasner Grant enabled me to undertake alternative therapy in Mexico while at the same time I was able to concentrate on creating an installation.’ Always transparent about the precarities she faced as a woman artist, Schneemann did not find steady commercial gallery support until after 1996.

Mortal Coils, 1994–95. Installation view at The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, 1997. Four projectors with motorised mirror systems, motorised manila ropes, ‘In Memoriam’ wall scroll texts, binders, lightbulbs, and sand. Photograph by Melissa Moreton. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Mortal Coils, 1994–95. Installation view at The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, 1997. Four projectors with motorised mirror systems, motorised manila ropes, ‘In Memoriam’ wall scroll texts, binders, lightbulbs, and sand. Photograph by Melissa Moreton. Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P·P·O·W New York and © 2022 Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London.

Legacy

Widespread critical recognition came late in Schneemann’s career, but she was unwavering in her knowledge of the value of her own work. In her studio, she kept an archive of images which tracked visual similarities between her art, advertising and pop cultural imagery, and works by other artists. As Schneemann took inspiration from those who came before her — her ‘missing precedents’ — countless artists today look to Schneemann and the force with which she expressed herself through art.

Image credit: Carolee Schneemann at her home in New Paltz, NY, 1996. Photograph by Joan Barker. Photo © Joan Barker