Exhibition Guide:

Jean Dubuffet

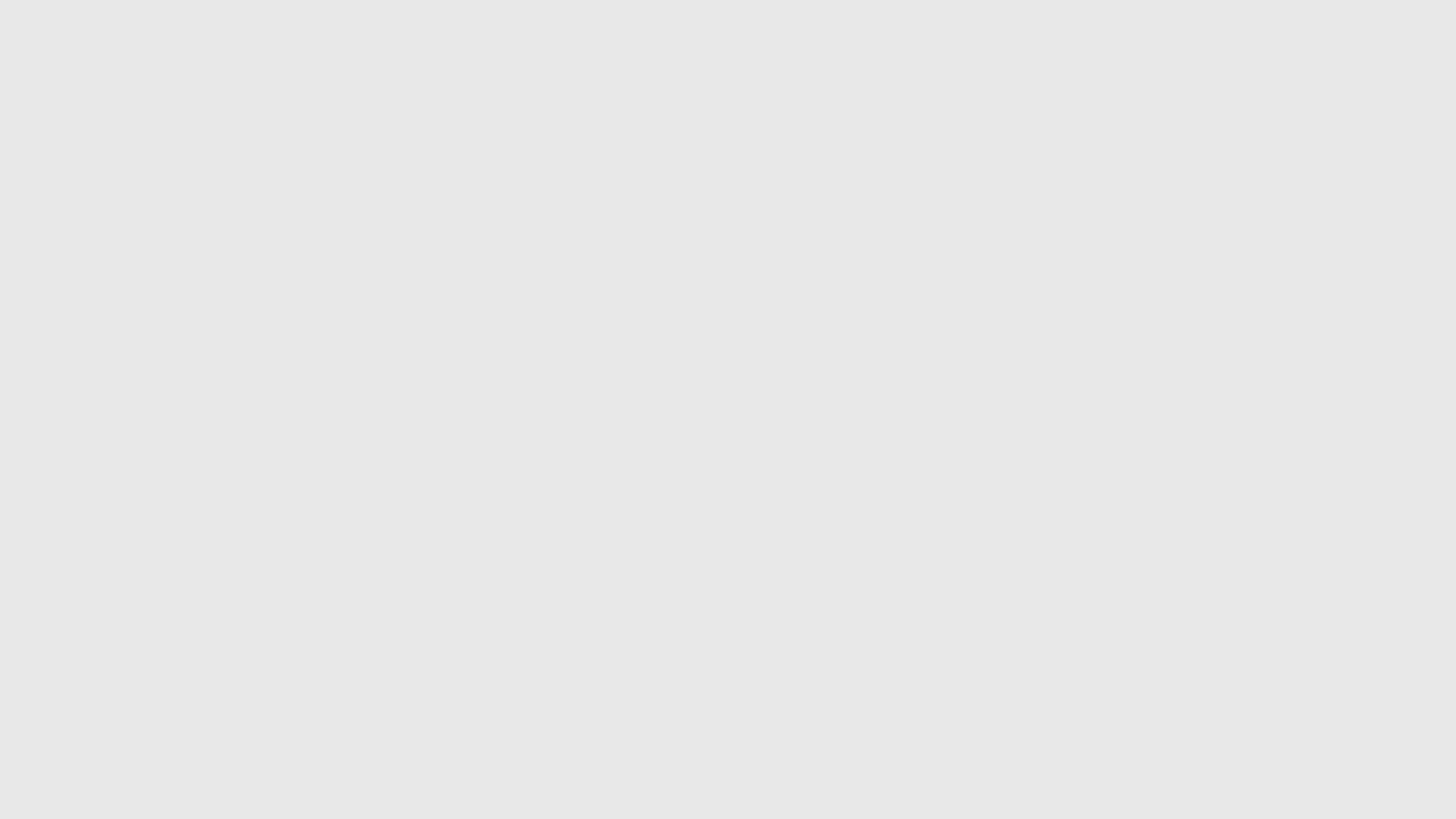

Brutal Beauty

Matter and Memory

‘I aim for an art that is directly plugged into our current life’

In June 1944, just days after American troops landed in Normandy, Dubuffet created a series in which he wrote graffiti-inspired messages onto French and German newspaper. The intimacy of these hand-written notes – ‘The key is under the shutter’; ‘I’ve been thinking of you’ – contrasts sharply with the formality of the typed news beneath. These fragile works reflect the swell of conflicting information at the time and the secret modes of communication that the Resistance fighters were forced to adopt in order to avoid persecution.

Dubuffet had long admired the photographer Brassaï, who had been documenting Parisian graffiti since the 1930s. Both were struck by the vitality of graffiti, which was anonymously authored but collectively addressed. Lithography (a type of printing based on the resistance of oil and water) was the perfect medium for the subject, as Dubuffet could attack the lithographic stone to recreate the textures of a defaced wall. The two series shown here, ‘Matter and Memory’ and ‘The Walls’ – accompanied by a text by Francis Ponge and a poem by Eugène Guillevic, respectively – give an impression of the endurance of everyday life despite the Occupation. Like Dubuffet’s paintings from this period, they speak to his belief that ‘the very basic … scribbles on a wall with a knife-point’ might have more ‘precious meaning than most … large pretentious paintings’.

Jean Dubuffet, Large Black Landscape (Grand paysage noir), September 1946, Tate © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London Photo © Tate

Jean Dubuffet, Large Black Landscape (Grand paysage noir), September 1946, Tate © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London Photo © Tate

Dubuffet at his exhibition at The Arts Club of Chicago, 27 December 1951. Photograph by Nathan Lerner © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Nathan Lerner

Dubuffet at his exhibition at The Arts Club of Chicago, 27 December 1951. Photograph by Nathan Lerner © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Nathan Lerner

True Face

‘Funny noses, big mouths, crooked teeth, hairy ears, I’m not against all that’

In the summer of 1945, Dubuffet made a number of portraits of his friend Jean Paulhan, a prominent French intellectual and former editor of the Nouvelle Revue française. Paulhan was critical in bringing Dubuffet’s revelatory work to the attention of a wider social circle in Paris – including the wealthy American expatriate Florence Gould, who hosted a weekly lunch at her home. When Dubuffet gifted her one of his Paulhan portraits, she suggested that he depict other guests from her salon; in August 1946 he wrote to her saying, ‘what an adventure you have thrown me on! Now it’s all I think about.’

With each sitter, Dubuffet spent hours just looking at them before returning to his studio to paint their portrait entirely from his recollection, creating what he called ‘a likeness burst in memory’. He made a thick paste from oil paint mixed with materials like plaster and varnish, which he would layer up and dust with sand or ash and then cut into with a scraper. Subverting the traditional genre of portraiture, Dubuffet set out to capture a kind of truth beyond resemblance. As his friend Georges Limbour described, the crudely rendered images seem ‘charged with a magical and hallucinatory secret power’. The portraits were exhibited together at the René Drouin gallery in October 1947 under the playful title People Are Much More Handsome than they Think. Long Live their True Face.

Art Brut

‘Millions of possibilities of expression exist outside the accepted cultural avenues’

In 1923, while working at the meteorological centre in the Eiffel Tower as part of his military service, Dubuffet came across drawings by the visionary Clémentine Ripoche. He was amazed by her sketchbooks, which were filled with scenes of tanks and carriages amid clouds. The following year, he discovered Hans Prinzhorn’s book Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922), but it was not until 1945 that he began actively to research ‘Art Brut’. He visited psychiatric institutions in Switzerland and France with the aim of publishing articles about artists working there. Two years later, he turned the basement of the René Drouin gallery into a ‘Foyer’ for exhibitions, and in 1948 he co-founded the Compagnie de l’Art Brut, which would collect more than 1,200 works by over 100 artists during its three-year existence.

This gallery (which is about the same size as the original Foyer) brings to life the experimental spirit of that space, featuring the work of eight artists selected by Dubuffet for a final exhibition in July 1948, which for unknown reasons never took place. By 1951, Dubuffet felt he was carrying the weight of the ‘Art Brut’ project alone. When the artist and collector Alfonso Ossorio offered to house the collection at his home on Long Island, New York, Dubuffet gratefully accepted, arranging for the precious works (and his filing cabinets of research materials) to be shipped across the Atlantic.

Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Composition No. 43, 1939, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne. Photograph by Marie Humair, Atelier de numérisation – Ville de Lausanne, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Composition No. 43, 1939, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne. Photograph by Marie Humair, Atelier de numérisation – Ville de Lausanne, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Jean Dubuffet, Lady’s Body (Corps de dame), June–December 1950, Galerie Natalie Seroussi © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London. Courtesy Galerie Natalie Seroussi, Paris

Jean Dubuffet, Lady’s Body (Corps de dame), June–December 1950, Galerie Natalie Seroussi © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London. Courtesy Galerie Natalie Seroussi, Paris

Ladies' Bodies

‘Nothing seems to be more false, more stupid, than the way students in an art class are placed in front of a completely nude woman … and stare at her for hours’

In April 1950, Dubuffet began work on a series that many considered his most controversial to date. First in paint and then using ink, he depicted female bodies that appear to have collapsed into a visceral landscape of flesh. He acknowledged that his imagery was violent but was clear that his attack was intended not at women but at the Western tradition of the female nude. In a catalogue text written for the Pierre Matisse gallery in New York in 1952, he explained that he wanted to protest against the ‘specious notion of beauty (inherited from the Greeks and cultivated by the magazine covers)’, which he found ‘miserable and most depressing’.

He started by mixing a thick paste from zinc oxide and a viscous varnish, applying it to the canvas with a putty knife to create ‘textures calling to mind human flesh (sometimes perhaps going beyond the point of decency)’. This mixture would repel oil paint, so that when he brushed on thin layers of sensual colours they would marble into unexpected patterns, suggesting the ‘invisible world of fluids circulating in bodies’. The amorphous figures, which lack clear definition, are reminiscent of ancient fertility statues, while botanical titles such as The Tree of Fluids reflect Dubuffet’s belief that ultimately we are all made from the same organic stuff: we come from, and will return to, the earth.

Mental Landscapes

‘It’s about the universe that surrounds us, the places that confront us, all the objects that meet our gaze and occupy our thoughts’

Dubuffet’s relationship to landscape painting was just as unusual as his approach to the female nude – and his work on these two traditional subjects partly overlapped. He did not want to capture a specific site or represent an idealized place; he considered these works a journey into ‘the country of the formless’. His interest in landscape sprang from three extended trips to Algeria between 1947 and 1949, where he learned Arabic and lived with Bedouin communities in the desert. He kept small sketchbooks while he was away and after returning to Paris tried to capture the spirit (rather than the likeness) of the extreme Saharan environments he had experienced.

This gallery, which presents work from 1952–53, shows Dubuffet’s interest in the interior of the mind as a kind of landscape. He thought of the brain as populated by a ‘disorder of images, of beginnings of images, of fading images, where they cross and mingle’. In these paintings, he coated canvas or hardboard with a thick putty to create a physical, tactile relief; similarly, his works on paper used a density of ink to give the impression of a ground teeming with energy and a mind brimming with thought. Typically, Dubuffet’s landscapes have a high horizon line and only a sliver of sky at the top, encouraging the viewer to devote more attention to the world beneath the surface.

Jean Dubuffet, Dazzling Glory of Earth and Sky (Éblouissante gloire de la terre et du ciel), September 1952, Private Collection © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London. Courtesy Private Collection

Jean Dubuffet, Dazzling Glory of Earth and Sky (Éblouissante gloire de la terre et du ciel), September 1952, Private Collection © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London. Courtesy Private Collection

Jean Dubuffet, Coursegoules, November 1956, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

Jean Dubuffet, Coursegoules, November 1956, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance

The Garden

‘I was fascinated by the tiny botanical world at the foot of walls’

Dubuffet’s question of how to animate materials found a more literal answer when he began using butterfly wings in 1953. He had been on holiday in Savoie with his friend Pierre Bettencourt, who had been catching butterflies and gluing them to paper, inspiring Dubuffet to experiment with his own butterfly collages. He arranged the wings into jaunty characters and ornate landscapes, inspired by the gardens in the South of France. The colours of the butterflies were more subtle than he expected, so he stained the background page and added touches of watercolour to dramatize the lustre of their wings.

Dubuffet had previously incorporated rough elements into his paint (shards of glass, twists of string), and he regularly used unusual tools (razor blades, sandpaper), but these were his first experiments with assemblage – a term he preferred to ‘collage’. He felt excited by the new technique, not least because it gave him a great deal of flexibility. In November 1955, he began creating and then cutting up oil paintings for new works, such as Coursegoules, which is a study of greenery pushing up between cobblestones. When the writer Alexandre Vialatte visited Dubuffet in 1956, he gave a vivid account of the scene: ‘Dubuffet is there, with a flowery hat and socks with green polka dots. He no longer paints with butter, cement, bitumen, but with shoemaker’s glue.’

Precarious Life

‘My feeling is, always has been … that the world must be ruled by strange systems of which we have not the slightest inkling’

In 1954, Dubuffet took his experiments with assemblage to a new dimension with his ‘Little Statues of Precarious Life’. He made these figures out of discarded materials, ranging from steel wool to newspaper, grapevine, charcoal and lava stone. For Character with Rhinestone Eyes, which is now the earliest surviving work from this series, he used the debris of a burnt-out car that he had found in the garage of his building. He revelled in the peculiar qualities of his materials, salvaging sponge, for instance, that had been deemed too ‘grotesque’ by a wholesaler. He turned these ordinary fragments into fantastical characters and tried to minimize his interventions.

That same year, he also began using quick-drying enamel paints, perhaps inspired by the American Abstract Expressionists, whose work he had admired on recent visits to New York. He mixed the industrial paints with oil, which created a ‘lively incompatibility’, especially as he worked into each thin layer before the last was fully dry. The technique generated what he called ‘strange bewildering worlds that exercise a kind of fascination’. Titles such as The Extravagant One feel fitting for the beguiling characters – part beast, part human – who emerge from the field of paint like phantoms in a dream.

Jean Dubuffet, The Extravagant One (L'Extravagante), July 1954, Private Collection, © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London. Photograph by Joseph Coscia Jr, courtesy Pace Gallery

Jean Dubuffet, The Extravagant One (L'Extravagante), July 1954, Private Collection, © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London. Photograph by Joseph Coscia Jr, courtesy Pace Gallery

Jean Dubuffet, Texturology XLVI (with ochre flashes) (Texturologie XLVI [aux clartés ocrées]), 30 May 1958. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2020, photograph courtesy Jean Tholance

Jean Dubuffet, Texturology XLVI (with ochre flashes) (Texturologie XLVI [aux clartés ocrées]), 30 May 1958. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2020, photograph courtesy Jean Tholance

Texturology

‘Teeming matter, alive and sparkling, could represent a piece of ground … but also evoke all kinds of indeterminate texture, and even galaxies and nebulae’

Dubuffet’s ‘Texturology’ paintings were inspired by the rich natural surroundings of Vence, where he moved in the hope that the fresh air would improve his wife Lili’s ailing health. Started in September 1957, they were originally intended to be cut into fragments for use in his series of ‘Topography’ assemblages. To make them, he borrowed a technique from Tyrolean stonemasons, who would shake a branch loaded with paint over fresh plaster in order to soften its colour. The delicate speckles of the ‘Texturologies’ have a spellbinding effect as they pivot between two extreme perspectives – the micro and the macro – reflecting on our place within the universe.

In 1959, the ‘Texturologies’ were exhibited at the Galerie Daniel Cordier in Paris under the title Celebration of the Soil, reflecting Dubuffet’s fundamental belief that humble matter, such as soil or the pavement, is worthy of our contemplation. With titles such as The Exemplary Life of the Soil or Grey-Beige Earth Element, the paintings bring attention to the subtlest nuances of the ground, in which Dubuffet saw expressions of an infinitely expanding cosmos. Conflating views of the earth, sky and stars, making the ground philosophical and the philosophical base, the ‘Texturologies’ were considered by Dubuffet to be ‘gadgets of fascination, exaltation, revelation: sort of divine services to celebrate living matter.’

Paris Circus

‘I want my street to be crazy, my broad avenues, shops and buildings to join in a crazy dance’

When Dubuffet returned to Paris in 1961, he had been away for six years. His retrospective had just closed at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, which led him to reflect on his earliest work. He wrote to his friend Geneviève Bonnefoi: ‘I live locked up in my studio doing, guess what? Paintings in the spirit and manner of those I was making in 1943. [I have] decided to start all over again from the beginning.’ But Paris had changed dramatically: the population had swollen and the postwar period of economic expansion had created a new consumer society. Dubuffet used billboards, cars, shop windows, restaurants and bars as symbols of this capitalist spectacle he called the ‘Paris Circus’.

As the title suggests, the works feature a kaleidoscope of imagery drawn from the frenzy of street life. The philosopher Max Loreau described how ‘Dubuffet has shed his ground-worshipper tunic to make way for the playful and theatrical Janus.’ As in his early paintings, each scene appears to have been flattened, the perspective deliberately skewed between a frontal and an aerial view, as if the city were reeling or drunk. In Paris-Montparnasse, made between 5 and 21 March 1961 and Dubuffet’s first oil painting in the series, a bus navigates a sprawl of urban traffic on the famous Left Bank. In later works such as Caught in the Act, cars jostle with shop signs reading ‘scoundrel’ or ‘underground bank’, suggesting the city’s seedy underside.

Jean Dubuffet, Caught in the Act (La Main dans le sac), 24–25 September 1961, Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Jean Dubuffet, Caught in the Act (La Main dans le sac), 24–25 September 1961, Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Adolf Wolfli, Insurgency Plan of St Adolf Castle in Breslau (Plan d’insurrection du chateau de St-Adolf a Breslau), 1922, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, Photograph by Arnaud Conne, Atelier de numérisation – Ville de Lausanne. Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Adolf Wolfli, Insurgency Plan of St Adolf Castle in Breslau (Plan d’insurrection du chateau de St-Adolf a Breslau), 1922, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, Photograph by Arnaud Conne, Atelier de numérisation – Ville de Lausanne. Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

The Collection Returns

‘Art Brut has been dormant during this vacation … but I am on the lookout’

After his return to Paris, Dubuffet wrote to Alfonso Ossorio pleading for his Art Brut collection to be sent home. He had been separated from it for over a decade and was desperate to be reunited. Ossorio asked to keep one or two works and Dubuffet implored him to be modest in his selection: ‘seeing several pieces separated is a sacrifice like losing an eye.’ In the end, at least 13 works remained in Long Island, and the rest of the collection was shipped back to Paris in the spring of 1962. Dubuffet had renovated a mansion on the rue de Sèvres into six galleries, with archives and offices. He personally installed the works in dynamic arrangements of old favourites and new acquisitions, mirrored in the selection of work by the eight artists presented here.

Dubuffet’s passion for Art Brut had been reignited: he reactivated his network of contacts and began to research and collect again. By 1963 he had acquired nearly 1,000 new works. When the drawings of the spiritualist Laure Pigeon were being thrown away after her death in 1965, it was he who was telephoned to see if he might save them. The larger spaces on the rue de Sèvres also allowed him to collect more sizable works, such as Émile Ratier’s towering wooden sculptures and Madge Gill’s vast calico drawings. Dubuffet’s involvement in Art Brut during this period catalysed a dramatic shift in his own practice – he felt compelled to create a truly immersive world for himself and his viewer.

L'Hourloupe

‘It is the unreal that enchants me now’

‘Hourloupe’ is an invented word that echoes the French entourloupe (to play a kind of trick) as well as hurler (to roar), hululer (to hoot) and loup (a male wolf). Dubuffet liked the animal associations, describing his word as sounding like ‘some wonderland or grotesque object or creature’. He used it for a new cycle of works that he had begun quite by accident while doodling on the telephone in July 1962. Using a four-colour ballpoint pen, he had made a series of fluid shapes and figures, which he embellished with blue and red stripes before cutting them out and placing them against a black background. These initial drawings became the gateway to an all-consuming series of paintings, sculptures, environments and performances that would occupy him for more than 12 years.

‘L’Hourloupe’ is characterized by sinuous webs with areas hatched or coloured in, primarily in red, white and blue. Sometimes images are enmeshed within the patterning, like a figure or a typewriter, creating visual confusion. Dubuffet wanted his meandering line to transform everything into a graphic surface, in order to remind us that the distinction between the so-called real and the imaginary is arbitrary. He was also clear that his ‘renewed interest in Art Brut’s productions was not unrelated to this sudden turning point’. Being surrounded by his collection again had sparked his interest in creating a stylized world of his own – ‘a dive into fantasy … a parallel universe’.

Jean Dubuffet, Skedaddle (L’Escampette), 31 October 1964, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, photo courtesy Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Jean Dubuffet, Skedaddle (L’Escampette), 31 October 1964, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, photo courtesy Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

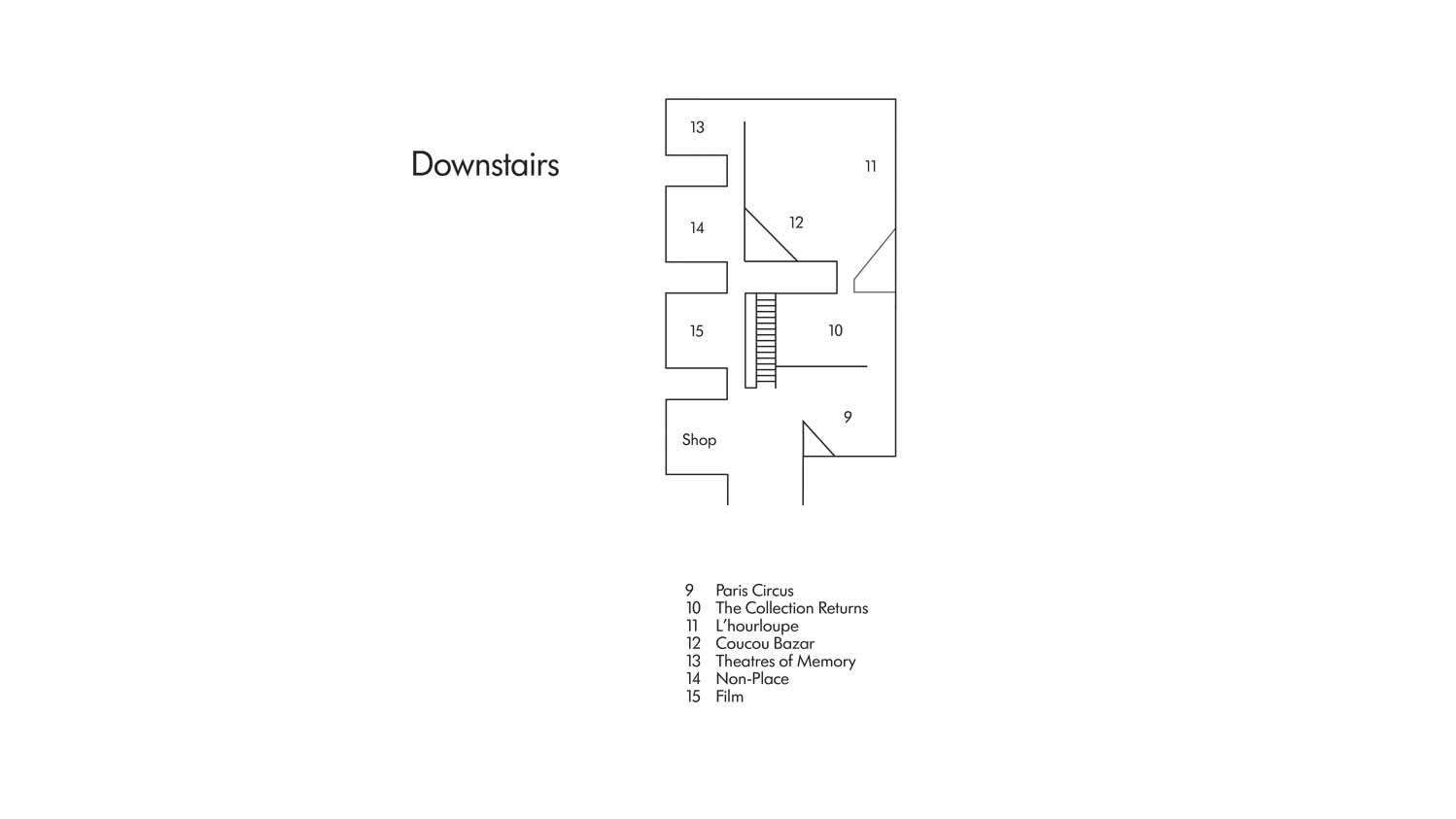

Dubuffet during rehearsals of Coucou Bazar in the auditorium of the Solomon R. Guggengeim Museum, New York, May 1973. Photograph by Robert E. Mates and Susan Lazarus © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / photograph Robert E. Mates & Susan Lazarus

Dubuffet during rehearsals of Coucou Bazar in the auditorium of the Solomon R. Guggengeim Museum, New York, May 1973. Photograph by Robert E. Mates and Susan Lazarus © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / photograph Robert E. Mates & Susan Lazarus

Coucou Bazar

‘It must not look like a theatrical production properly speaking but like a painting’

From 1971 to 1973, Dubuffet worked in a former munitions factory in Vincennes to fabricate 175 freestanding elements based on his ‘L’Hourloupe’ work. He called these ‘theatrical props’ (praticables); some were mounted on metal stands and others had electronic mechanisms to allow them to move independently. A selection of these objects, joined by dancers wearing costumes that he had also designed, featured in his performance Coucou Bazar at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1973, timed to coincide with his retrospective there.

According to the handout, the one-hour ‘spectacle’ involved 60 artworks ‘animated and articulated by various means’. The non-narrative scenes were accompanied by dramatic lighting and a musical score by the composer İlhan Mimaroğlu, which Dubuffet specified should be ‘brutally loud with abrupt interruptions of silence’. The ‘living painting’ was performed again at the Grand Palais in Paris, and in 1978 Dubuffet devised a new version for Turin, with revised choreography and his own music. The elements are now too fragile for the work to be restaged as Dubuffet originally intended, but this installation gives a sense of how intimately Coucou Bazar connected to Dubuffet’s broader ‘L’Hourloupe’ project: ‘it is a painter’s work rather than a playwright’s … Painting is its only parent.’

Theatres of Memory

‘These assemblages have mixtures of sites and scenes, which are the constituent parts of a moment of viewing … the mind recapitulates all fields, it makes them dance together’

For his ‘Theatres of Memory’, made between October 1975 and May 1979, Dubuffet returned to assemblage, layering fragments of paintings into enormous collages that evoke a mind swarming with thoughts and images. He installed metal panels in his studio so that he could arrange and rearrange the cut-out elements using small magnets before settling on a final composition. Given that he was now 75, these large-scale works were physically challenging to produce; Vicissitudes is more than 3.5 metres wide and so required ‘a good deal of gymnastic exercise on a ladder’.

The title of the series refers to The Art of Memory (1966) by Frances Yates, a book about the mnemonic techniques used by classical orators. The chaotic imagery in these panoramic ‘theatres’ reflects Dubuffet’s interest in how our imagination bleeds into our impressions of the everyday world. When they were exhibited at Pace Gallery in New York in 1979, the works attracted the attention of artists including Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The graphic black-and-white drawings that Dubuffet made using felt-tip pen in 1978–79 form a dialogue with the work of this younger generation. The name of the wider series, ‘Circumstances, Records, Rememberings’, suggests that Dubuffet was thinking of both how we remember and what kind of memory his own work might leave behind.

Jean Dubuffet, Vicissitudes (Les Vicissitudes) January 1977, Tate: Purchased 1983 © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © Tate

Jean Dubuffet, Vicissitudes (Les Vicissitudes) January 1977, Tate: Purchased 1983 © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © Tate

Jean Dubuffet, Mire G 177 (Bolero), 28 December 1983, Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London, photo courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

Jean Dubuffet, Mire G 177 (Bolero), 28 December 1983, Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London, photo courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

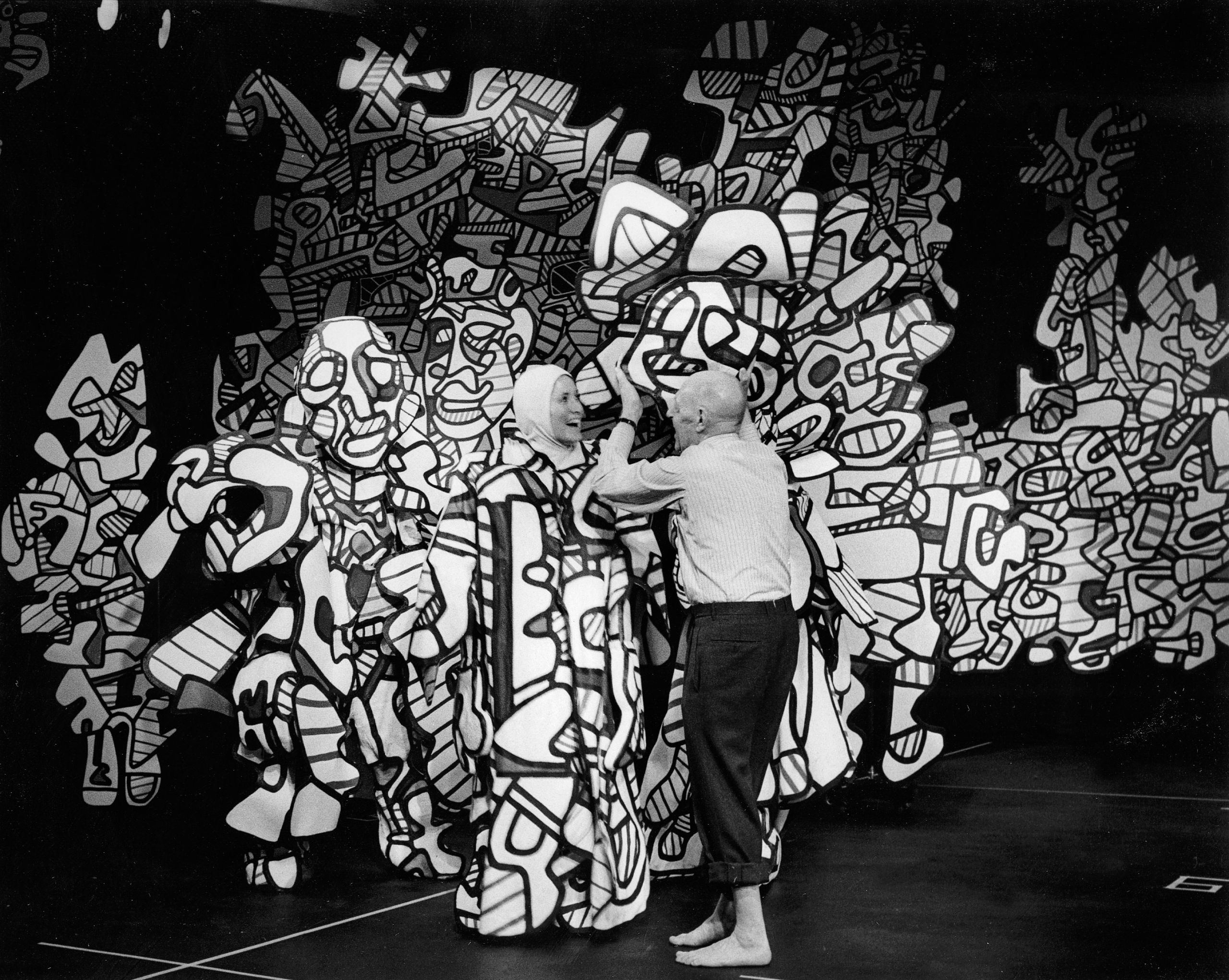

Non-place

‘I have been concerned … to represent not the objective world, but what it becomes in our thoughts’

In 1984, Dubuffet exhibited in the French pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Ever inventive, he presented a radical new series called ‘Mires’. Each work features a dense cluster of interweaving lines and shapes in primary-coloured acrylic. Sitting at a table (to give respite to his back), he painted on individual sheets of copy paper which he then tiled together into larger works, such as the epic Mire G 177 (Bolero) of 28 December 1983. Unlike his recent ‘Theatres of Memory’, the compositions featured no recognizable imagery, reflecting Dubuffet’s lifelong oscillation between the body and the landscape, figuration and abstraction. The mark-making also references his ongoing interest in graffiti, a subject that had inspired him for more than 40 years.

Dubuffet followed this series with another, titled ‘Non-Places’, which features similarly bold lattices of colour. Now aged 83, he was questioning existence with the same fervour as in his earliest philosophical musings on matter. Both of these bodies of work demonstrate Dubuffet’s commitment to exploring interior and exterior, mind and matter, as no longer distinguishable spaces. They exemplify his relentless interest in painting as a tool to interrogate reality and to propose alternative possibilities. As he wrote in a letter to Arne Glimcher, founder of Pace Gallery, he wanted ‘to challenge the objective nature of being’. The ‘Non-Places’ were to be his final series of paintings: Dubuffet died, at his desk, on 12 May 1985.

Credit: Jean Dubuffet, 'Paysage aux argus' (Landscape with Argus), 1955. Collection Fondation Dubuffet, © Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / DACS, London 2019. Image courtesy of Fondation Dubuffet, Paris.

Credit: Jean Dubuffet, 'Paysage aux argus' (Landscape with Argus), 1955. Collection Fondation Dubuffet, © Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / DACS, London 2019. Image courtesy of Fondation Dubuffet, Paris.

A Note on Art Brut

Dubuffet was engaged in radically rethinking what can be considered art and who can make it. He coined the term ‘Art Brut’ in 1945 to refer to the work of artists operating outside the professional art world, which possessed ‘a special quality for personal creation, spontaneity, and liberty’. Here, he felt, was true originality. In English ‘Art Brut’ is often called ‘Outsider Art’, but we have chosen to avoid this term since Dubuffet fought against such cultural hierarchies. Brut roughly translates as ‘raw’, which might sound harsh to our ears, although Dubuffet simply meant it in contrast to the ‘refined’ beaux-arts; as a former wine merchant, he likely also enjoyed the implication that this work was as brut (or dry) as fine champagne.

Art Brut remains contested – what gave Dubuffet the prerogative to acquire this work and to speak on the artists’ behalf? He claimed to draw inspiration from the spirit rather than the style of these artists, but might that still be considered an appropriative act? Later in life, Dubuffet also acknowledged his romanticism about the ‘pure and authentic creative impulses’ of these artists, recognizing that no one can live in complete isolation from cultural influence. The 16 artists presented in these two exhibition spaces, who have been selected in collaboration with the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, represent just a fraction of Dubuffet’s collection, yet their remarkable vitality makes clear why Dubuffet found himself so captivated and why he dedicated so much of his life’s energy to championing their work.

Photograph by John Craven © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © John Craven

Photograph by John Craven © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © John Craven

Featured Artists

Miguel Hernandez, Aloïse, Maurice Baskine, Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Joaquim Vicens Gironella, Henri Salingardes, Gaston Chaissac, Jan Krížek, Gaston Duf., Augustin Lesage, Laure Pigeon, Madge Gill, Adolf Wölfli, Auguste Forestier, Sylvain Lecocq, Scottie Wilson

Artist Biographies

Miguel Hernandez (1893–1957)

Born in Ávila, Spain, Hernandez emigrated to Brazil aged 19 to pursue his dream of becoming a coffee grower. He settled in Rio de Janeiro, where he was employed as a cook for a group of socialist revolutionaries, which inspired his future anarchist views. He returned to Europe in 1923 and later settled in Madrid. In 1936, when the Spanish Civil War broke out, he joined the Popular Front. He fled the country two years later and escaped to France, where he was interned in a refugee camp for Spanish exiles. In 1945, following the liberation of France, he moved to Paris and set up a small studio, where he created drawings and paintings. Dubuffet presented Hernandez’s work at the Foyer in 1948 and curated a solo exhibition of his artwork the following summer. Records show that Dubuffet purchased work directly from Hernandez and that the two corresponded for several years prior to the collection’s transfer to the United States.

Aloïse Corbaz, known as Aloïse (1886–1964)

Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, Aloïse dreamt of having a career as an opera singer. In 1911 she left Switzerland and worked as a governess in Germany, but the outbreak of the First World War forced Aloïse to return to Switzerland. In 1918 she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and admitted to the Cery psychiatric hospital, where, shortly after her admission, she began drawing and writing. Initially working in secret, she drew with lead pencil and ink on paper, all of which she destroyed. However, her artistic expression was noticed by the doctor Jacqueline Porret-Forel, who provided Aloïse with drawing materials to complete her brightly coloured, often figurative works. Porret-Forel introduced Dubuffet to Aloïse’s work and he visited the hospital to meet her in December 1948. He proceeded to visit her several times and remained awestruck by Aloïse’s work, praising her ‘great mastery over mise-en-page’.

Maurice Baskine (1901–1968)

Born in Kharkiv, Ukraine, Baskine moved to Paris with his family when he was four years old. In the late 1930s he discovered texts written by the seventeenth-century Scottish alchemist Alexander Seton, whose ideas inspired him to begin creating art. In May 1940, during the Second World War, Baskine entered the French army, and he was later imprisoned by the Nazis. In 1944, after escaping, he joined the French Resistance. The following year he participated in an exhibition at the Katia Granoff gallery in Paris, where he showed a series of paintings called ‘Le Temple du Mas’ (‘Farmhouse Temple’), which attracted the attention of Dubuffet. He later wrote to Baskine, introducing himself (‘Maybe you know my name? I am a painter too’) and expressing interest in co-authoring an article. Baskine replied shortly after, confirming that he would be happy to meet and have his work photographed. Although never acquired for the Art Brut collection, Baskine’s work was closely followed by Dubuffet, who planned to include him in the final exhibition at the Foyer de l’Art Brut in 1948.

Fleury-Joseph Crépin (1875–1948)

Crépin was born in Hénin-Liétard, northern France, where he later owned a plumbing and hardware store. Alongside his business, he enjoyed music and took part in several performances. In 1930 Crépin was introduced to spiritualism, which would lead to him becoming a spirit healer. Aged 64, while transcribing music, his hand began to freely trace small drawings, and a few months later he produced his first work of art. He made a series of paintings that he said were dictated to him by spirits and which he called his ‘marvellous paintings’. Crépin devoted himself fully to his creative practice, producing works featuring dreamlike temples and architectural scenes with rigorous symmetry and rendered in countless droplets of paint and varnish. Dubuffet discovered Crépin’s work in an exhibition organized by the French Spiritist Union in Paris in September 1946 and was so fascinated by it that he had it photographed for inclusion in his photo albums devoted to Art Brut.

Jan Křížek (1919–1985)

Born in a small village in the former Czechoslovakia, Krížek enrolled in the sculpture studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1938. His artistic education ended abruptly with the outbreak of the Second World War, but he continued to study independently, immersing himself in the library of the city’s Museum of Applied Arts, where he explored subjects including architecture, religious art, anatomy and molecular physics. In 1946 he visited Paris for the first time before moving there the following year. As he could not afford artistic materials, Krížek often made sculptures using the rubble from demolition sites or pre-existing clay works, which he would soak and then remodel. These small-scale sculptures, which have echoes of pre-Columbian and ancient Greek and Roman statues, attracted the attention of Michel Tapié, who featured more than 18 of them in a solo presentation at the Foyer de l’Art Brut in February 1948. Praised by critics, who described his sculptures as ‘curiously unusual’, Krížek was admired by leading cultural figures including art critic Charles Estienne, writer André Breton and artist Pablo Picasso.

Gaston Chaissac (1910–1964)

Born in Avallon, France, Chaissac left school early and worked in various odd jobs before starting an apprenticeship as a cobbler. He began making art in 1936, but his output was slowed by illness and the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1942, Chaissac moved with his wife to the Vendée region in western France, where he immersed himself in creative production. As well as poetry and drawing, he made sculptures using a diverse range of materials, including rock fragments, shells, roots, branches, brooms, old doors and planks. In 1944, Dubuffet discovered the work of Chaissac in Paris. The two began corresponding and stayed in contact until Chaissac’s death, sending more than 440 letters to one another. Despite this frenzied correspondence, their friendship was tumultuous and Dubuffet later recategorized Chaissac’s work within his collection of Art Brut, transferring it to an annexed section that included works produced.

Henri Salingardes (1872–1947)

Salingardes was born in Villefranche-de-Rouergue, France, where his parents owned and ran a small restaurant. After finishing school he worked as a hairdresser before relocating to Paris. In 1922 he bought a small inn located in the Tarn region of southern France and began buying and selling antiques in his spare time. At the age of 64 (when his children had taken over his business) he started making medallions from poured cement, featuring reliefs of strange figures, birds and animals. He enjoyed working in the garden of his inn, using ochre powders to colour the cement before decorating the surfaces with paint, glass, fur and other materials. He produced a large number of these cement works, which joined his rich assortment of antique furniture at the inn and hung from the wisteria on the terrace. In 1943, a train accident resulted in the amputation of one of his legs and brought a dramatic end to his artistic pursuits. His medallions were included in several group exhibitions at the Foyer de l’Art Brut and were some of the earliest works to enter the Art Brut collection.

Joaquim Vicens Gironella (1911–1997)

In 1948, while still working as a wine merchant, Dubuffet visited the office of René-Bernard Lajus, a cork manufacturer based in Paris. Lajus’s office was decorated with more than 30 sculptures carved in cork, and they immediately captured Dubuffet’s attention. These artworks were hand-carved by Gironella, who worked in Lajus’s cork factory in Toulouse. Born in Agullana, in the Catalan Pyrenees, he had grown up in a family of cork manufacturers, who taught him the trade. Fervently anti-fascist, he joined the Spanish army in 1936 but was forced into exile following the victory of General Franco. After escaping to France, Gironella was imprisoned in the internment camp in Aude, where he remained until the country’s liberation in 1941. After moving to Toulouse, Gironella started sculpting in clay but soon switched to cork, devoting himself fully to the material. He sometimes worked from a chalk sketch, but he usually carved freehand using a file and a pocket knife. These works, which illustrate mythological scenes, religious figures and landscapes, were presented in several exhibitions at the Foyer de l’Art Brut, including a solo presentation curated by Dubuffet in the winter of 1948.

Gaston Dufour, known as Gaston Duf. (1920–1966)

Duf. was born into a family of ten children in the mining region of Pas-de-Calais, France. After finishing school he worked as a baker and a miner but was dismissed due to alcoholism and ill health. His reliance on alcohol and his withdrawn and hostile behaviour led to him being admitted to the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu psychiatric hospital in 1940. Several years after his admission, Duf.’s doctor discovered that he had been hiding drawings in the lining of his clothes. Completed in lead pencil in the margins of newspapers, the drawings depicted imaginary creatures and monstrous-looking beasts. Following his discovery, the doctor gave Duf. paper, coloured pencils and tubes of gouache so that he could continue creating art. Dr Paul Bernard, who worked with Duf., corresponded with Dubuffet from 1948 and donated 30 of Duf.’s drawings to the Art Brut collection.

Augustin Lesage (1876–1954)

Lesage was born in Pas-de-Calais, France, to a family of coal miners and started working in the mines at an early age. In 1911, while at work, a disembodied voice told him that he would become a painter, and after conducting a series of séances he began to make drawings. Urged by spirit voices, Lesage bought paint and canvas to create an enormous work measuring 9 square metres that took more than a year to complete. Lesage said: ‘A picture comes into existence detail by detail, and nothing about it enters my mind beforehand. My guides have told me: 'Do not try and find out what you are doing.' I surrender to their prompting.’ In 1923, Lesage moved to Paris and started working exclusively as a spiritualist painter, for which he received widespread attention. In 1964, Dubuffet acquired Lesage’s First Canvas, which he described as an ‘enormous and marvellous painting’.

Laure Pigeon (1882–1965)

Pigeon had a strict upbringing in Brittany, France, where she lived with her grandmother. Against her family’s wishes, she married a dental surgeon and moved to Paris. After 22 years she separated from her husband and moved to a boarding house, where a fellow resident introduced her to spiritualism, which she began to practise in isolation. Her earliest drawings date from 1935 – intricate webs of blue and black ink that undulate across the page and contain abstract figures and messages. Pigeon produced hundreds of these drawings, which she believed were dictated to her by spirits; each was meticulously dated and categorized before being hidden from view. In spring 1963 Dubuffet visited the House of Spiritualists in Paris, and started subscribing to The Spiritualist Review (La Revue spirite). It was through these circles that he discovered Pigeon’s delicate drawings, which he greatly admired; he described how ‘the steady range of Laure’s lines is an astonishing feat in itself’. After Pigeon’s death in 1965, Dubuffet was contacted and he rescued the trove of work and writing that had been left behind, unwanted.

Madge Gill (1882–1961)

Gill was born in Walthamstow, east London. In 1900, after spending her childhood in Canada, Gill returned to London and later started working as a nurse. While her husband, Tom, was serving in the Second World War, their son Reggie died from Spanish flu related pneumonia, a loss that left Gill devastated. In early 1920 she experienced her first vision and an overwhelming need to make art, which prompted an outpouring of work: ink drawings on paper and calico, pages of writing and numerous textiles. The trauma of her son’s death paired with Gill’s severe health problems led to her being admitted to the Lady Chichester Hospital, Hove. Run by the progressive doctor Helen Boyle, the hospital encouraged Gill in her art making, and she continued producing work after she was discharged. Often rejecting authorship of her works, Gill attributed them to a spirit guide called Myrninerest: ‘Sometimes, at his dictation, I write for hours covering hundreds of postcards with a strange script.’

Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930)

Born in a village outside Bern, Switzerland, Wölfli was the youngest of seven children. He grew up in very precarious circumstances and after the death of his mother was placed with numerous foster families before finding work as a farm labourer. After a romantic rejection, he returned to Bern and led a relatively isolated life, working as a handyman. In 1890 he approached a 17-year-old girl and attempted to molest her. After spending two years in prison, his behaviour was reported as increasingly strange and he was prone to violent, explosive fits of anger. In 1895, Wölfli was arrested again and admitted to the Waldau psychiatric clinic in Bern, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. In his first years at Waldau he was extremely agitated, which changed when he began making art. A dense world began to emerge: musical notes, animals, masked faces, architectural structures and mandala-like forms, all enclosed within ornate and decorative borders. He produced an enormous body of work, including more than 25,000 pages of graphic compositions, literary works and musical scores. Dubuffet discovered Wölfli’s work on his trip to Switzerland in 1945 and was rendered ‘speechless in front of these exceptional creations’.

Auguste Forestier (1887–1958)

Forestier was born in Lozère, France, to a farming family. He was fascinated by trains; aged 27, he experimented with placing piles of stones on the railway tracks, keen to understand how the train wheels would crush the obstacle. This heap of stones derailed an oncoming train and Forestier was consequently admitted to a psychiatric hospital. There, he worked in the institution’s shop and kitchen. He drew in his spare time, working with coloured pencils on paper to make medals that he wore, and carved sculptures out of bones that he had saved from the kitchen. Forestier later built a small workshop in one of the hospital corridors, where he focused on woodcarving: using pieces of salvaged wood and a cobbler’s leather knife, he carved human figures, animals and small vehicles which he then decorated with leather, fabric, medals and string. He also made moving toys for the nurses’ children in the hospital to play with, and often displayed his works for sale on the walls of the hospital courtyard.

Sylvain Lecocq (1900–1950)

Born just outside Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, Lecocq was the son of a shoemaker. He worked as a tradesman before marrying and having three sons. After an operation on an ulcer in 1942, he had to give up work, which led him to withdraw into an imaginary world, writing countless mystical and philosophical texts. In 1947, Lecocq was admitted to the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu psychiatric hospital outside Lille, his medical file specifying ‘active delirium with mystical themes’. During his time at the hospital he started salvaging materials such as blotting paper, cardboard and brown parcel paper, which he used as supports for writing and drawing, resulting in an enormous creative output of poems, love letters, songs and drawings. Lecocq committed suicide in 1950. Two years earlier, Dubuffet had begun corresponding with Dr Paul Bernard, one of the doctors at the hospital. Bernard shared several drawings by a patient with Dubuffet, who in response sent drawing materials to the hospital for the residents to use. Dr Bernard later donated more than 100 of his patients’ works, including pieces by Lecocq, to Dubuffet.

Scottie Wilson, born Louis Freeman (1888–1972)

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, Wilson was the son of a Russian Jewish émigré. He did not go to school and was illiterate, but he defiantly rejected any suggestion that he lacked intelligence: ‘my mind is reading all the time. I don’t need papers or books. My mind is full of books.’ After serving in the army aged 16, he worked in circuses and fairgrounds before setting up a small travelling shop that he took to many of London’s markets. Aged 40, he decided to take up drawing and soon devoted himself to making art. Wilson’s drawings, executed in pen and ink and detailed with colourful cross-hatching, often feature human figures, animals and malevolent characters that he called ‘Evils’ and ‘Greedies’. Wilson began selling his drawings inexpensively and exhibiting them in a variety of settings, which drew the attention of key art world figures including the artist Roland Penrose. In the early 1950s, Wilson travelled to Paris to meet Dubuffet – who had started collecting his work after being introduced to it by Penrose and the art dealer Victor Musgrave.

Miguel Hernandez, 1951. Photograph by Robert Doisneau © Robert Doisneau / Gamma Rapho / Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Miguel Hernandez, 1951. Photograph by Robert Doisneau © Robert Doisneau / Gamma Rapho / Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Aloïse Corbaz, Cery hospital, 1948. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Aloïse Corbaz, Cery hospital, 1948. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Maurice Baskine, date unknown.

Courtesy Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain,

Cordes-sur-Ciel

Maurice Baskine, date unknown.

Courtesy Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain,

Cordes-sur-Ciel

Fleury-Joseph Crépin, c. 1946. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Fleury-Joseph Crépin, c. 1946. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Front cover of Sculptures of Krížek (Sculptures de Krížek), exhibition catalogue, 1948. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Front cover of Sculptures of Krížek (Sculptures de Krížek), exhibition catalogue, 1948. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Gaston Chaissac, August 1952. Photograph by Robert Doisneau © Robert Doisneau / Gamma-Legends via Getty Images

Gaston Chaissac, August 1952. Photograph by Robert Doisneau © Robert Doisneau / Gamma-Legends via Getty Images

Henri Salingardes, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Henri Salingardes, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Joaquim Vicens Gironella, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Joaquim Vicens Gironella, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Front cover of the fifth Art Brut Booklet (Fascicules de l’Art Brut, no. 5), Compagnie de L’Art Brut, Paris, 1965. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Front cover of the fifth Art Brut Booklet (Fascicules de l’Art Brut, no. 5), Compagnie de L’Art Brut, Paris, 1965. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Augustin Lesage, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Augustin Lesage, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Laure Pigeon, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Laure Pigeon, date unknown. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Madge Gill working on a large work on fabric at her home in East Ham, London, 19 August 1947. Photograph by Paul Popper © Paul Popper / Popperfoto via Getty Images

Madge Gill working on a large work on fabric at her home in East Ham, London, 19 August 1947. Photograph by Paul Popper © Paul Popper / Popperfoto via Getty Images

Adolf Wölfli, c. 1920. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Adolf Wölfli, c. 1920. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Gérard Vulliamy, Auguste Forestier, 18 July 1945. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Gérard Vulliamy, Auguste Forestier, 18 July 1945. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Cover of Five Little Painting Inventors (Cinq petits inventeurs de la peinture), exhibition catalogue, 1951. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Cover of Five Little Painting Inventors (Cinq petits inventeurs de la peinture), exhibition catalogue, 1951. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Scottie Wilson, 1967. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Scottie Wilson, 1967. Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Listen to the Jean Dubuffet playlist

Shop the exhibition

This fully illustrated book is published by Prestel and designed by the Bon Ton. An introductory text is written by the curator, Eleanor Nairne, alongside rich and insightful thematic essays by Kent Mitchell Minturn, Rachel E. Perry, Sarah Wilson, Sarah Lombardi, Sophie Berrebi and Camille Houzé.

Prints from the exhibition are also available to purchase in the Art Gallery Shop or online.

Explore Brutal Beauty

Learn more about the life and work of French artist Jean Dubuffet, the subject of our summer exhibition Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty in this series of articles, videos and podcasts.