‘Some martians landed in Central Park today,’ Johnny Carson quipped on his television show in 1972. ‘They were mugged.’ The comedian’s joke about soaring crime rates in the five boroughs - from a talk show that had once been based in New York - was more than a little bit damning for the inhabitants of the cash-strapped city.

By the late ‘70s, New York City was reeling from near-bankruptcy, serial killers on the prowl, and a blackout that had, with subsequent looting, led to an estimated $300 million dollars in damage. But beyond financial struggles, the city was also suffering from a loss of morale. Once the most celebrated and gleaming metropolis in the nation - a beacon of American innovation - it was now crumbling and derelict, with fires breaking out in abandoned buildings and a murder rate that had doubled in a decade. Such was the sense of danger, vigilantes, youth gangs, and even local patrols of armed civilians (like The Guardian Angels) could be found roaming the city streets.

These were the Carter administration’s ‘malaise’ years - and the spirit of a city in disintegration couldn’t help but to seep into the various artistic enclaves there. In New York’s independent film world, which had been riotously bursting to prominence since the sixties, new guerilla filmmakers armed with Super-8 cameras were on the prowl. Many borrowed from the same casts and crews, utilising tiny budgets and the favours of friends to capture the vibrant chaos of the city around them. This came to be known as the no-wave movement, a loose, mixed bag of diverse filmmakers from Susan Seidelman to Abel Ferrara.

Mirroring the grimy, ad-hoc aesthetic of DIY punk bands and visual street artists of the time, the no wave film movement was not one of strict manifestos. In fact, Pitchfork writer Marc Masters rightly refers to the spirit of no wave as defined by a lack of dogma; a ‘philosophy of rejection’. Whether it be the luridly violent output of Scott and Beth B or the taste-pushing sexual transgressions of Richard Kern, the films were less stylistically coherent than they were bound together by a shared locality and scene. Downtown personalities like Nan Goldin, Lydia Lunch, or Richard Hell appear frequently, and impromptu screenings were held at now iconic music venues like Max’s Kansas City or the Mudd Club, where Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat famously hung out. What no wave films did share was a cheap and cheerful approach and a real sense of the aggression of city living - bolstered by the music that underpinned the movement.

‘You painted, you were in a band, you made films, you wrote songs'

Seizing on the lowbrow, the taboo, and the scruffy cool of the surrounding music and art scene, disciplines were often mixed. As Lydia Lunch says, ‘You painted, you were in a band, you made films, you wrote songs. It was just all so interconnected. We were all friends and freak-by-nature outsider artists. I think it was just the freak nature of our base elements that brought us together.’

Fittingly, a noisy, resentful style of music was also gestating in lower Manhattan in the late ‘70s. The era was the harbinger of punk and no-wave, and among New York’s leading proponents were Television, Suicide, Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers, Richard Hell, Patti Smith, and Blondie. All of these groups found their members wandering the environs of New York’s Lower East Side, swapping booze, instruments, and most likely spit at the same grimy downtown music venues.

One of the most legendary of those venues, CBGB’s, became the focal point for film recordings of those musicians and their performances. The Blank Generation, one of the earliest ‘home movies’ from the club, features a roughly-edited collection of musical performances that capture the propulsive energy of foot-stomping punk from bands like The Ramones.

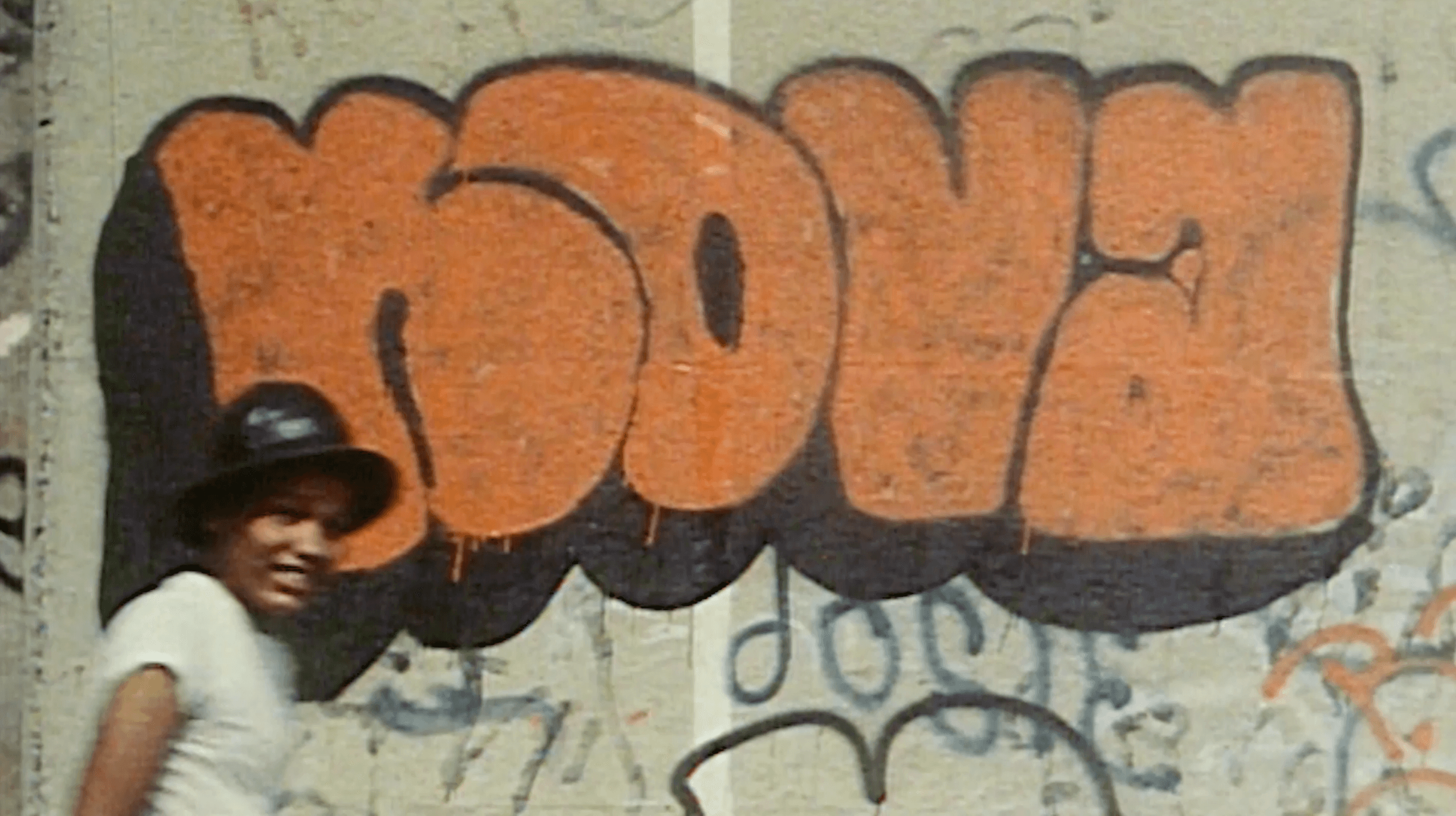

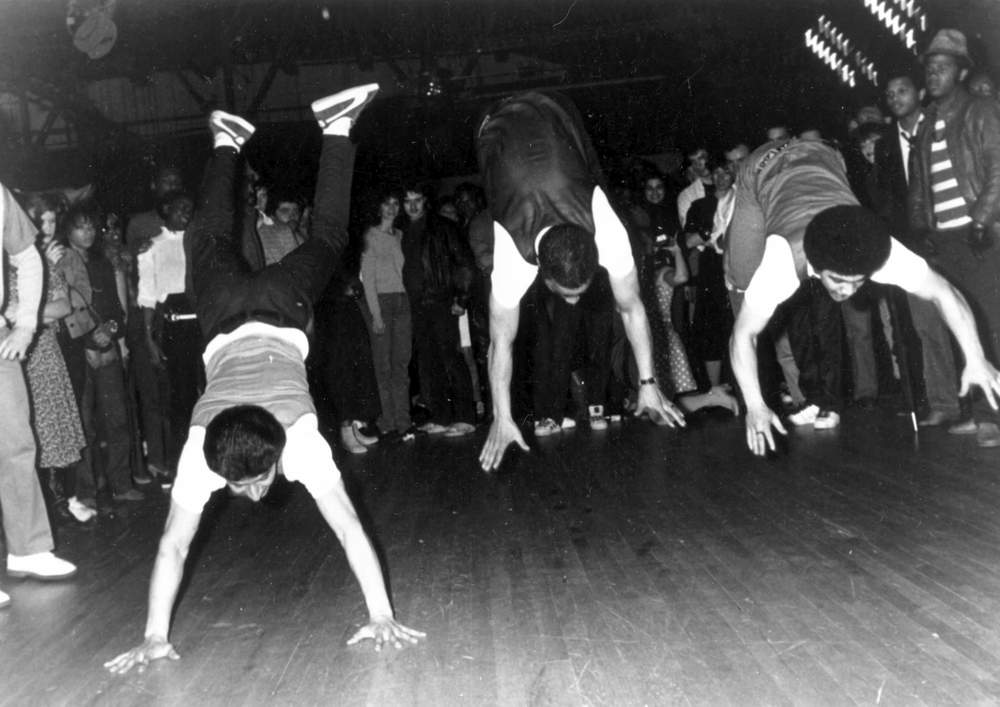

Music seemed to be a guiding force for the no wave filmmakers, who were often interested in recording and sharing the internal workings of their subculture with a wider audience (and for posterity.) This was as much the case with hip-hop as it was with punk. Iconic docu-fiction Wild Style was filmed over the course of three years by Charlie Ahearn. Inspired by conversations with pioneering rapper Fab 5 Freddy, who appears in the film, the film is one of the very first to depict the seedling musical activities of the black community in the Bronx. Breakdancing, graffiti art, emceeing and turntabling all feature heavily in Wild Style, and the focus is much more on the realities of outlaw street artists than on its loose semblance of plot.

Trailer for Wild Style (1983)

In actuality, Ahearn used the thin veneer of fiction to get his film into the biggest Times Square/42nd Street cinemas - knowing they didn’t typically screen documentaries. The legendary status of the film - and the seminal figures who appear in it, including Grandmaster Flash - have led to portions of it being sampled across a selection of great hip-hop records. Nas, A Tribe Called Quest, MF Doom and others have all paid homage to the influential power of Wild Style.

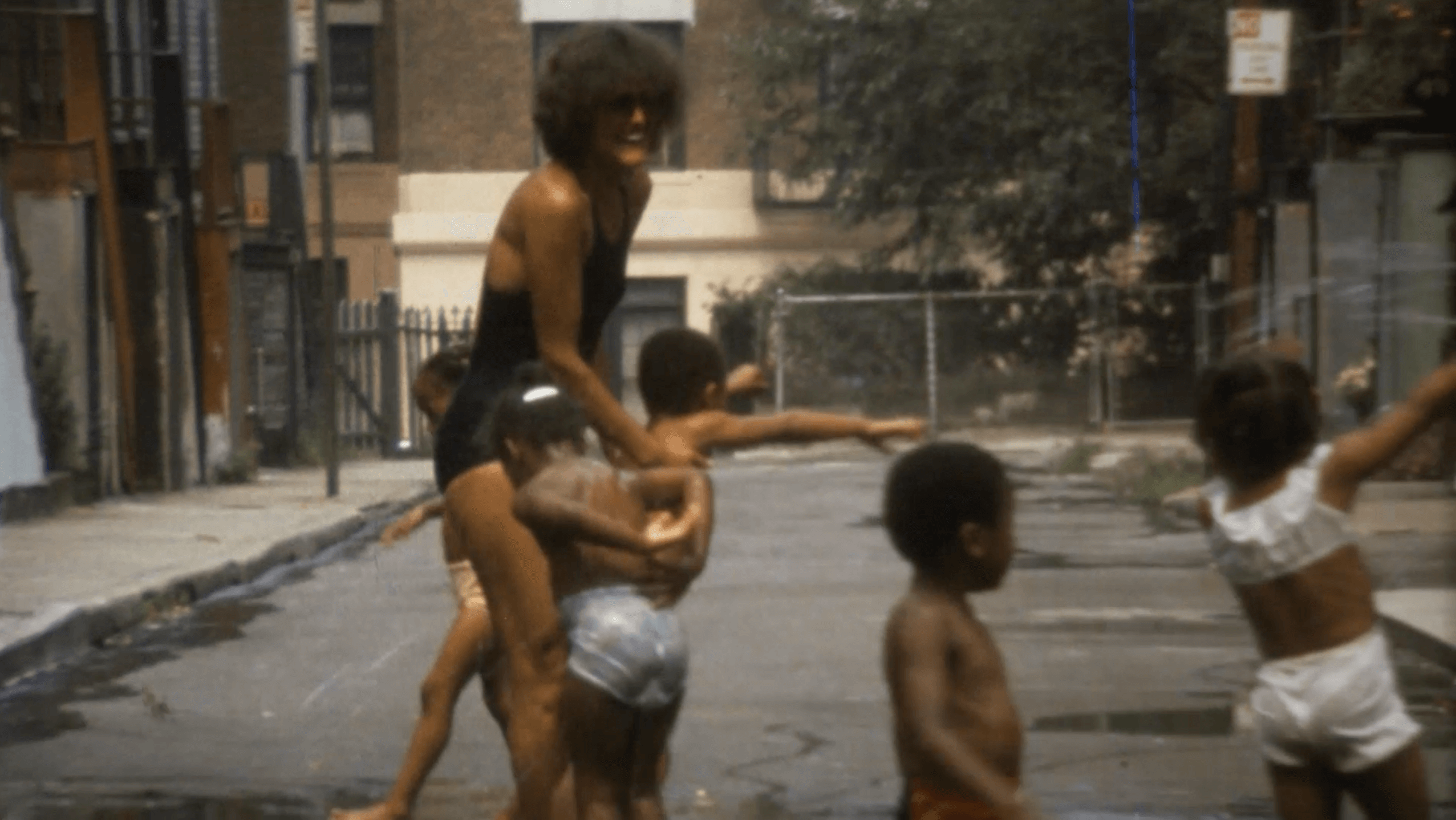

Still from Wild Style (1982)

By the early 1980’s, the areas around the Lower East Side became well-known neighborhoods for outsiders and artists to live affordably. In spite of the crack dens and junkies who roamed the streets at night, it was also a place where creative people from all over could reinvent themselves. People flocked to downtown, creating a lively community of cheap dive bars and street art galleries.

Perhaps one of the greatest illustrations of this mecca for weirdos is Jim Jarmusch’s debut feature from 1980, Permanent Vacation.With his already-recognisable deadpan approach, Jarmusch shot the meandering film on 16mm and with help from longtime collaborator and actor John Lurie. In it, the lead (Chris Parker) meets a rogue’s gallery of eccentrics as he wanders through the East Village, with Jarmusch’s bumpy tracking shots guiding us through the strange rubble of vacant lots and abandoned buildings. Jarmusch has had a long career in making films about foreigners who feel like Americans and Americans who feel like foreigners - and Permanent Vacation, along with Stranger than Paradise, both revel in this feeling.

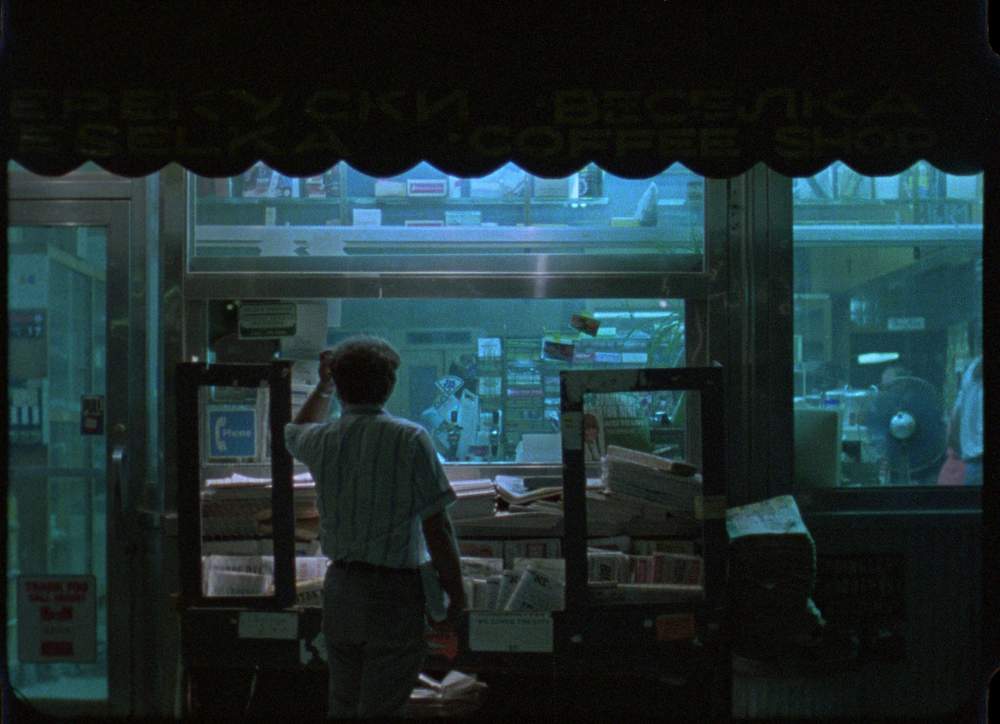

That sense of urban loneliness is shared by Chantal Akerman, perhaps one of the most far-flung of filmmakers to capture No Wave New York. The Belgian director made her brief, poetic News from Home while wandering the city streets with her handheld Bolex camera. All her lingering shots of the city are external; no warm interiors are to be found Though she captures the alienation of expat life, Akerman still finds a melancholy beauty in the city. In voiceover, the director shares snippets of phone calls with her mother back in Europe. ‘Be careful going out alone at night. New York is dangerous.’ Akerman is warned.

Blondie’s Debbie Harry could certainly attest to that - the risks of living in squatter’s digs and trawling around downtown neighborhoods were not to be understated. This is often lost in the heady nostalgia of it all, but for Harry, it was a distinct reality. She once hitched a ride with notorious serial killer Ted Bundy - before jumping out of his car in terror and likely escaping with her life.

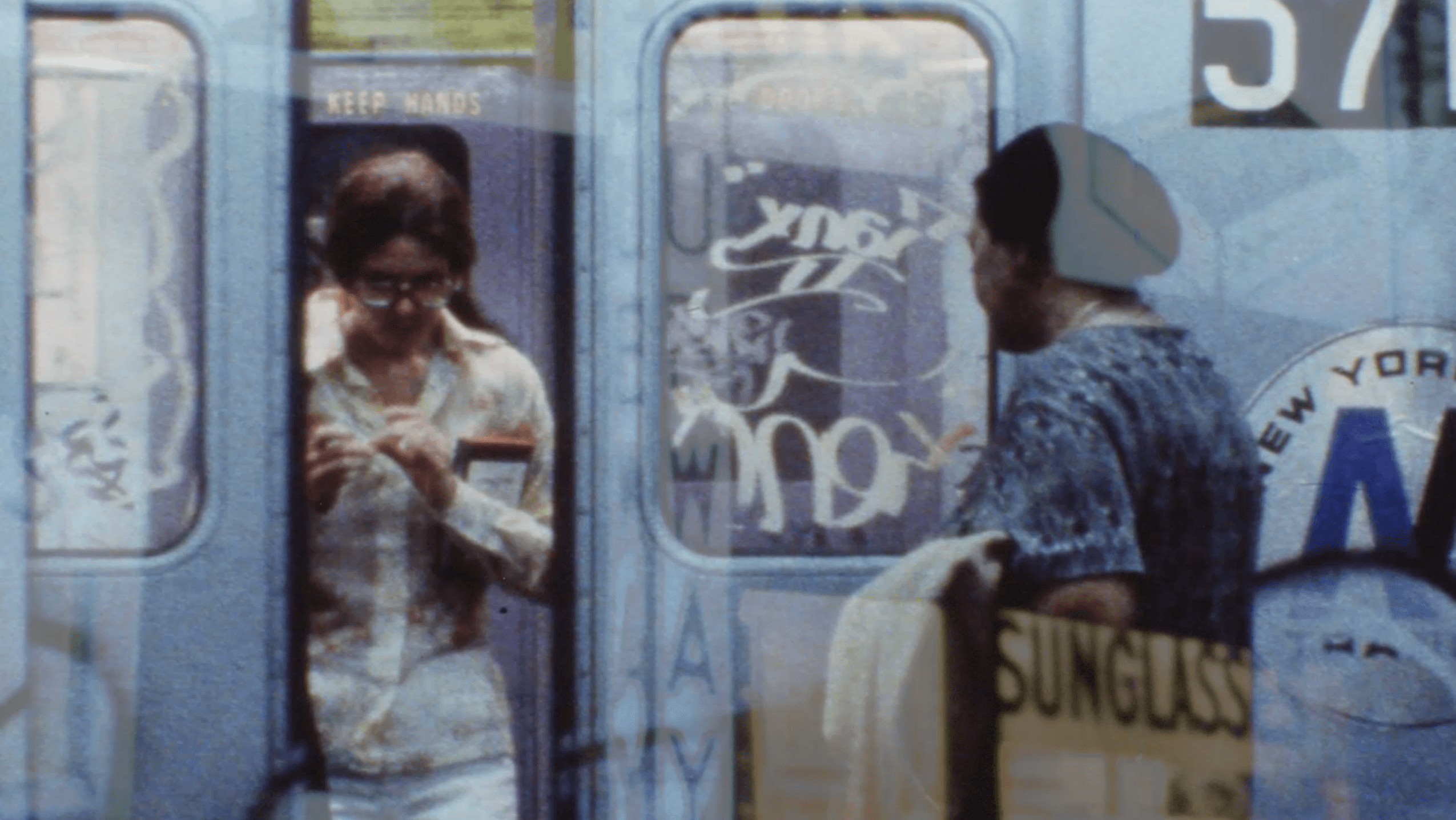

Still from News From Home (1977)

Female protagonists in no wave films of the eighties are surprisingly omnipresent. This was in no small part due to the abundance of women writers and filmmakers active at the time. Female directors like Bette Gordon, Susan Seidelman, and Lizzie Borden were key players of the New York independent scene at a time when mainstream Hollywood was still sorely lacking in those perspectives. Beyond merely portraying women against the backdrop of downtown Manhattan, many of these films were caught up in ideas of female identity, sexuality, sexual subversion, and a feminist compulsion to kick Reaganite values in the teeth.

As Susan Seidelman points out: ‘Being an 'indie' filmmaker meant that you are not just the director, but often the producer, editor, screenwriter, casting director, music supervisor and location scout, rolled into one. As a result, these films all had a very personal vision. It was an opportunity for a new generation of women, who had been excluded from mainstream film production, to make their own kind of movies — and on their own terms.’

Trailer for Smithereens (1985)

Seidelman also made her debut feature in the milieu of the no wave, with her small-budget dark comedy Smithereens (1982). Starring Sandy Berman as a New Jersey girl who comes to Manhattan in the hopes of living a glamorous punk lifestyle, Seidelman vibrantly captured the trendy sleaziness of the era. Her protagonist is often unlikeable, with a winking eye toward the posers and hangers-on that had flooded the scene.

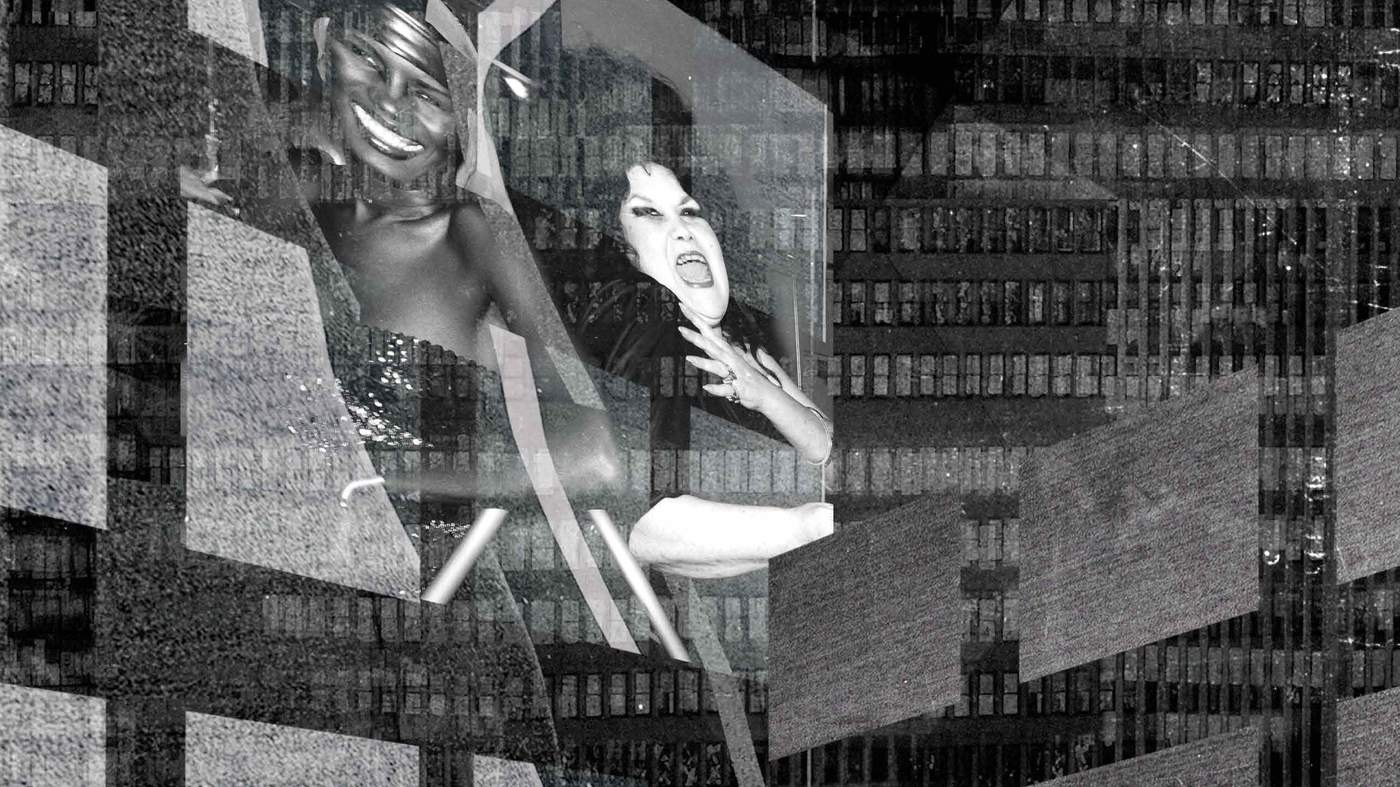

Still from Smithereens (1982)

Seidelman suddenly found herself in receipt of a $4.5 million budget for her next film, Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), and cast a fresh-faced, barely-famous Madonna in the outspoken lead role. Both of Seidelman’s films are markedly more optimistic than Ferrara’s when it comes to the striving young women of New York. In Seidelman’s vision, even if they are far from perfect, these women are free to change their style, attitudes, and identities in any way they wish, away from the judgement of more staid suburban locales.

Trailer for Desperately Seeking Susan (1985)

In hindsight, there’s a deep cultural cache around those precarious years of New York’s squalor and creativity. From the burning tenements of the South Bronx where hip hop was born to the pornography theatres of Times Square where Travis Bickle decries the filth of the city (and the female protagonist of Bette Gordon’s Variety happily works), the era has become a flashpoint of subsequent attention and glorification.

It must seem strange to the varied collection of squatters and avant-garde dabblers who peopled CBGB’s and the Mudd Club at the time.

But seen now - through the prism of Donald Trump’s sterile dominion of Manhattan real estate - the last pre-gentrification gasps of grimy New York seem more inspiring by the day.

About The Grime and The Glamour: NYC 1976–90

Get a taste of the scuzzy and blisteringly creative streets of late 1970s and 80s New York City, with films by Susan Seidelman, Chantal Akerman, Jim Jarmusch and Bette Gordon

The season took place from 29 Sep-5 Oct 2017

About Basquiat: Boom For Real

Basquiat: Boom for Real is the first large-scale exhibition in the UK of the work of American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960—1988). Drawing from international museums and private collections, Basquiat: Boom for Real brings together an outstanding selection of more than 100 works, many never before seen in the UK.

The exhibition took place in the Barbican Art Gallery from 21 Sep 2017-28 Jan 2018.

Archive footage courtesy of Kinolibrary