Introducing:

Jean Dubuffet

A key figure in postwar modern art, Dubuffet tried to capture the poetry of everyday life in a gritty, more authentic way. Camille Houzé looks back through his life, works and legacy.

Early Life

Jean Dubuffet was born on 31 July 1901 in the city of Le Havre, France. The elder son of a wealthy family of wine merchants, he grew up under the watchful eye of his authoritative father, Georges, who expected him to excel at school. The young Dubuffet found solace in the family’s extensive library, stealing books and reading them at night by torchlight. His passion for reading was overtaken at the age of seven, when he saw a woman painting landscapes by the roadside. He started making little paintings in secret which he hid in a briefcase and then destroyed – ‘fearful of being deceived by the admiration I had for them’.

Dubuffet’s imagination became a source of escape and he started collecting unusual objects and materials such as fossils, beetles, cassava roots and sandalwood, which he displayed in his ‘museum’ – a wardrobe he had converted for this purpose.

At school, Dubuffet met the future Surrealist writer Georges Limbour, who would become his closest friend and the first critic of his work. Excelling in his classes, Dubuffet developed an interest in philosophy and literature, reading the works of Schopenhauer, Dostoevsky and Baudelaire. His true love, however, remained the visual arts and, in 1916, he started taking night classes in drawing and painting at the School of Fine Arts in Le Havre, which cemented his desire to become a professional artist. Two years later, after protracted negotiations with his sceptical father, Dubuffet enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris.

Dubuffet and Limbour rented a room in the bohemian Latin Quarter of Paris but he became quickly disenchanted with the teaching at the Academy – which he deemed pretentious and superficial – and decided to leave after six months.

'It didn’t take me long to realize that no education was provided in this academy … We were chasing girls, wearing black hats and our hair long … badges of artistic honour. After a few months this spirit changed. Influenced by exhibitions of avant-garde paintings and modernist writings, I became convinced that artistic creation had to be anchored in everyday life – the black hat was replaced by a populist cap.'

This criticism foreshadowed a lifelong revolution against established academic traditions and made him realize that he would do better to create his own syllabus of favourite subjects, which included philosophy, literature and ethnography. While toying with the idea of becoming a writer, he stayed connected to the art world, and befriended a group of older artists including the painter Suzanne Valadon and the poet Max Jacob. He and Limbour would also visit the studio of artist André Masson, whose practice inspired Dubuffet to begin a new series of paintings. However, these were soon halted when, in 1923, he ‘reluctantly’ carried out his military service.

Dubuffet aged four, Le Havre, 1905 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Dubuffet aged four, Le Havre, 1905 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Jean Dubuffet aged 18 or 19, c. 1919–20 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Jean Dubuffet aged 18 or 19, c. 1919–20 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Dubuffet during his military service playing with Jeanne Léger’s monkey, Fontenay-aux-Roses, 1924 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Dubuffet during his military service playing with Jeanne Léger’s monkey, Fontenay-aux-Roses, 1924 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

An altered vision

After a few months stationed in a fort he was moved to the Meteorological Office in the Eiffel Tower, where he found a sketchbook belonging to the visionary Clémentine Ripoche. Dubuffet was fascinated by her drawings of scenes amidst the clouds and he went to visit her on the outskirts of Paris, enlivened by this remarkable discovery. The following year, he was introduced to a book which would alter his entire artistic vision: Hans Prinzhorn’s Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Published in 1922, Prinzhorn’s text was a ground-breaking study into the relationship between mental illness and creativity and it received a great deal of attention from avant-garde artists including Max Ernst and Paul Klee. Dubuffet was awe-struck by the artworks in the book and later recounted that ‘I realized that millions of possibilities of expression were available outside of the accepted cultural avenues’.

While this encounter with these works was revelatory, it made him question his own artistic potential, and the purpose of art altogether. Dubuffet destroyed most of his work and decided to travel to Buenos Aires – he would not create another painting for the next nine years.

By the time he went back to making art in 1933, Dubuffet had established his own wine business in Paris, married Pauline Bret – the daughter of a company client –, who gave birth to their daughter Isalmina in 1929. The success of his business enabled him to rent a studio in Montparnasse, where he started painting again with renewed dedication and excitement. Spending every afternoon at his studio, his absence caused a rift with his wife and they decided to divorce in 1934. While affected by the breakdown of his marriage, Dubuffet seized the opportunity to delegate his business commitments to an associate and start making art again. He devoted himself to his practice fully, later recalling:

‘Disaster! Here it goes again... I did not want to hear about anything, I was doing my painting: everything around me could scream, catch on fire, collapse! What a breather, what joy!’

The following three years were celebratory. Dubuffet met Émilie Carlu (known as Lili) in a café in Montparnasse and the two quickly fell in love. Dubuffet adored their bohemian lifestyle and they transformed their home into a theatre where he played the accordion, sculpted and painted. In 1937, however, Dubuffet’s world changed when he learned that his wine company was on the brink of bankruptcy, forcing him to abandon art for the second time. Following the outbreak of the Second World War two years later, Dubuffet was drafted into military service, only returning to Paris in 1940. He started illegally transporting wine from the Free Zone to Paris and the monetary success of this operation allowed him to pay off the entirety of his company’s debts within the next two years. Dubuffet could finally devote himself to painting and he gave himself ‘carte blanche’ to ‘paint freely and quickly… experimenting in all directions and even preferably [rejecting] common sense’.

Dubuffet and Lili, 1935 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Dubuffet and Lili, 1935 © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris

Jean Dubuffet, Wall with Inscriptions (Mur aux inscriptions), April 1945, The Museum of Modern Art, New York © The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

Jean Dubuffet, Wall with Inscriptions (Mur aux inscriptions), April 1945, The Museum of Modern Art, New York © The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

Rehabilitation of scorned values

The desolation of the war accentuated Dubuffet’s contempt for conventional ideas of beauty and aesthetic refinement. He was interested in the grittier textures of everyday life: the uninhibited drawings of children, the graffiti on the walls of Paris and the recently discovered paintings in the Lascaux caves in Southern France. In his creative output, he chose to celebrate everyday life by focusing on commonplace things: shop signs and building facades, figures performing daily tasks, the bustling Parisian Metro, and the materiality of graffitied walls. Dubuffet was striving to create art that spoke to who he called ‘the common man’, which would resonate with the broadest demographic of people – far from the elitism of the Academy. ‘Don’t cut art off from the world and lock it up in a Trappist monastery’, he declared:

‘I want painting that smells of all those things – decorations, distempers, signs, placards, and outlines drawn in the earth by heels. Those are primal soils of origin’.

His studio on rue Lhomond began attracting numerous visitors, including literary figures such as Paul Éluard, Francis Ponge, and Jean Paulhan, the influential writer and former editor of the Nouvelle Revue Française. The latter introduced his work to the gallerist René Drouin, who organized Dubuffet’s first solo exhibition in October 1944. He gained an immediate reputation as a rebellious figure whose work divided the opinions of his audience. Visitors were often shocked by the childlike rendering of his figures and the heavy materiality of his paintings, which in the postwar context re-energized moral tensions around ideas of purity and defilement – in 1946, a critic famously declared: ‘after Dadaism, here is Cacaism’.

Art Brut

Although deliberately avoiding any political commentary or affiliation, Dubuffet positioned himself as the avenger of scorned values, celebrating instinctual modes of creation over Western notions of reason, beauty and logic. It was in this spirit that he conceived the concept of ‘Art Brut’. Literally translating to ‘raw’ art, the term ‘Art Brut’ was developed after a trip to Switzerland where he visited several psychiatric hospitals to meet with patients and doctors and view their collections of artworks. He was rendered ‘speechless in front of these exceptional creations’ and this trip marked the beginning of his collection of works by those he viewed as ‘untouched by artistic culture’, including psychiatric patients, tattooists, spiritualists, self-taught artists, and incarcerated individuals.

In 1947, Dubuffet created the Foyer de l’Art Brut in the basement of the René Drouin gallery, where he began exhibiting works from his collection. The following year he co-founded, with writer André Breton, Paulhan, and art critic Michel Tapié, the Compagnie de l’Art Brut, which would collect more than 1200 works during its three-year existence. In 1951, however, Dubuffet dissolved the company, complaining about the lack of support from other members. He arranged for the works and all his research files to be sent to the United States, where the artist Alfonso Ossorio had offered to house the collection in his mansion in Long Island, New York. The collection would remain there for ten years.

Anticultural positions

Dubuffet used this opportunity to travel to the US, where he was the subject of an exhibition at the Arts Club of Chicago and delivered his famous lecture Anticultural Positions. He had already attracted the attention of major American artists and critics since 1947, when Pierre Matisse began exhibiting his work in his gallery in New York; Jackson Pollock was an admirer, and Clement Greenberg called Dubuffet ‘the most original painter to have come out of the school of Paris since Miró’. However, his lecture at the Arts Club, in which he described Western culture as ‘a dead language’ and called for an art ‘directly plugged into our current life’, confirmed Dubuffet as one of the most provocative voices in postwar modernism – Keith Haring, for instance, would declare in 1977 that ‘few [texts] have had such simple, profound effect’ on his practice.

Jean Dubuffet, Garden with Melitaea (Jardin aux Mélitées), 4 September 1955, Collection Fondation Dubuffet, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London

Jean Dubuffet, Garden with Melitaea (Jardin aux Mélitées), 4 September 1955, Collection Fondation Dubuffet, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London

For Dubuffet, being ‘anticultural’ meant drawing the viewer’s attention to the materiality of paint itself and advocating for a closeness to raw matter and organic forms. ‘Look at what lies at your feet!’, he wrote, ‘a crack in the ground, sparkling gravel, a tuft of grass, some crushed debris offer equally worthy subjects for your applause and admiration.’

Whether painting female nudes or landscapes, he treated the canvas as a visceral object, conceiving his painting recipes as concoctions of living matter.

Let the Material Speak for Itself was the appropriate title of a text written by Limbour in the catalogue of Dubuffet’s exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, in 1955.

Cosmic Ground

During the 1950s, this philosophy translated into successive series of works celebrating soil and earth, where Dubuffet saw a relationship between the ground beneath our feet and the inner textures of the mind. From 1953, he became increasingly interested in organic materials, creating assemblages with butterfly wings, as well as characters and landscapes using botanical elements. At the same time, he salvaged all sort of refuse materials – sponges, clinker, charcoal, car debris – to create the Little Statues of Precarious Life, a carnival of extravagant characters through which he investigated the vitalism of inert matter. In Vence, a city in Southern France where he moved in 1955 to find a better climate for Lili’s ailing health, Dubuffet explored derelict gardens and country roads, using aerial dripping techniques to recreate the surface of pavements in which he saw expressions of an infinitely expanding cosmos.

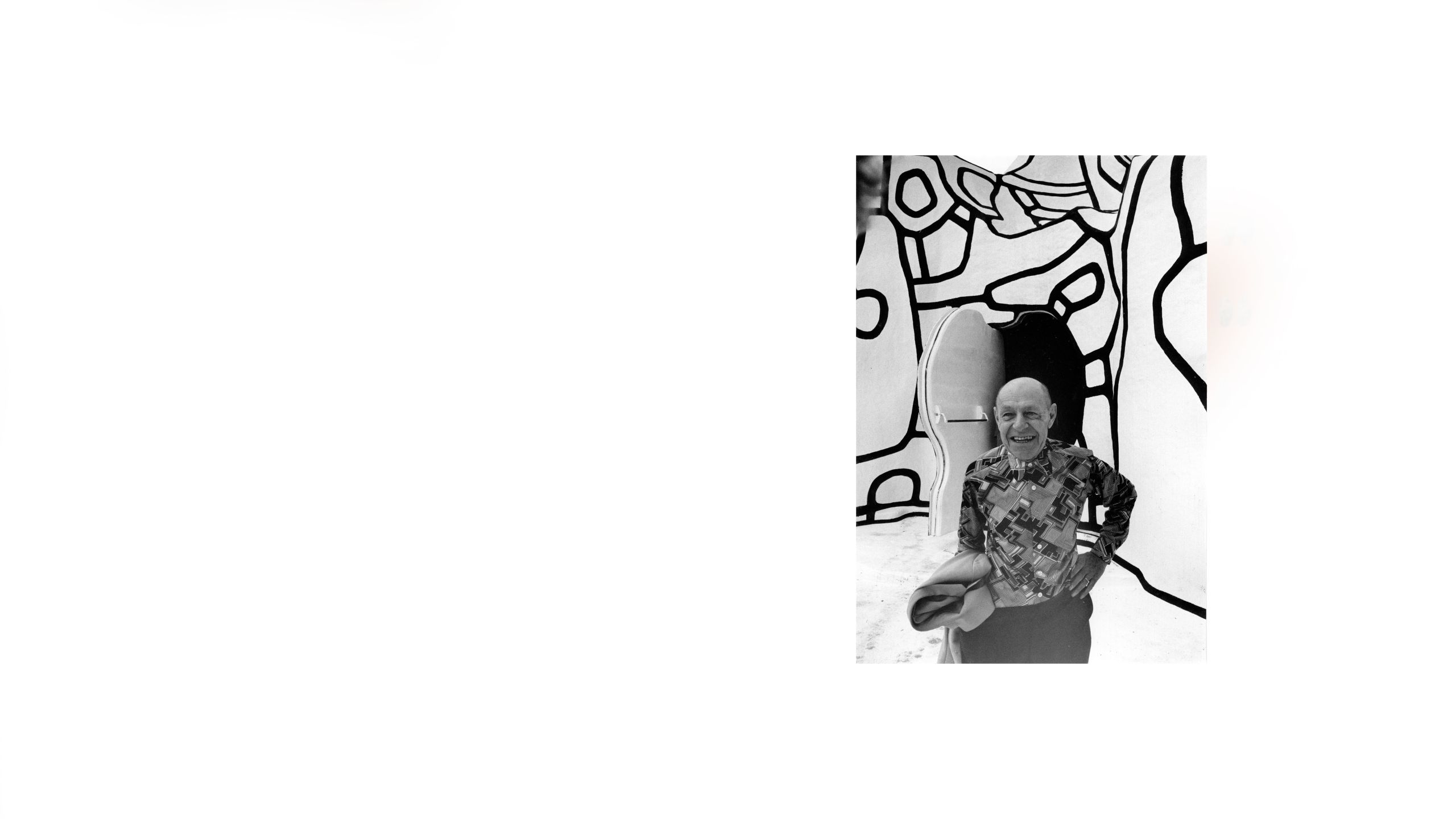

Dubuffet in Paris, 1964. Photograph by Ida Kar © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Ida Kar, National Portrait Gallery, London

Dubuffet in Paris, 1964. Photograph by Ida Kar © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Ida Kar, National Portrait Gallery, London

Dubuffet in Paris, 1964. Photograph by Ida Kar © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Ida Kar, National Portrait Gallery, London

Dubuffet in Paris, 1964. Photograph by Ida Kar © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Ida Kar, National Portrait Gallery, London

Dubuffet in Paris, 1964. Photograph by Ida Kar © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Ida Kar, National Portrait Gallery, London

Dubuffet in Paris, 1964. Photograph by Ida Kar © Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / © Ida Kar, National Portrait Gallery, London

Meandering lines of flight

The 1960s were radically different. His return to Paris in December 1960, where his first retrospective in a French museum opened at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, prompted an abrupt shift in subject matter. Inspired by the city’s intense urban activity, he created a series called Paris Circus, which comprised paintings and gouaches depicting frenzied street scenes through an explosion of colours and dense puzzles of pedestrians, buses, and shopping centres. In 1962, Dubuffet’s collection of Art Brut was returned after its stay with Ossorio. He bought a property on the rue de Sèvres in Paris where he created gallery spaces to display the collection and established a second Compagnie de l’Art Brut.

Jean Dubuffet, Caught in the Act (La Main dans le sac), 24–25 September 1961, Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Jean Dubuffet, Caught in the Act (La Main dans le sac), 24–25 September 1961, Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London © Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

The return of his beloved collection had a significant impact on his practice and ignited Dubuffet’s desire to create ‘a phantasmagorical parallel universe’ of his own. As he wrote to Paulhan, ‘the lesson I drew from Art Brut is that real creation begins only at this stage of homogeneous and uninterrupted production… the art that I aim for consists of developing a uniform project, an element without beginning or end, without limits or centre, like the high seas.’ These ideas materialized in L’Hourloupe, a cycle of work including paintings, sculptures, architectural environments and theatrical performances which would occupy Dubuffet for twelve years.

With a palette reduced almost exclusively to red, white and blue, he created an infinitely proliferating visual language based on an unbroken, meandering line through which he attempted to convey the feeling of a continuity between all things.

He painted his figures, objects, and places in such a way that they seem to constantly appear and disappear, plunging the viewer into a dense web where distinctions between the real and the imaginary no longer apply. As he explained, ‘L’Hourloupe’ has the possibility of ‘introducing a doubt about the true materiality of the everyday world [which may also] be a mental construct.’

Jean Dubuffet, Nunc Stans, 16 May – 5 June 1965, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Jean Dubuffet, Nunc Stans, 16 May – 5 June 1965, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Naming the unnamable

This philosophical reflection would define Dubuffet’s late artistic period. His previous focus on worldly matter had now been replaced by a desire for lightness and artificiality. He abandoned heavy mixtures of paint for synthetic materials including vinyl, polystyrene, polyester and Styrofoam, which he used to create expanded sculptural environments such as the Villa Falbala and the adjoining Closerie (1971–73), realizing his dream to create a habitat secluded from the world. The titles of his major late series – Theatres of Memory (1975–78); Mires (1983–84); and Non-Places (1984) – demonstrate an increasing interrogation of the nature of reality and existence.

‘If I should decide whether or not there is a reality’, he wrote, ‘I doubt the validity of both the notion of reality and the notion of existence. It is not only that I doubt it, I am convinced that these notions, which nevertheless form the basis of our thinking, are devoid of any foundation’.

Physically weakened by years of intensive work, Dubuffet nevertheless continued to produce relentlessly, making almost an artwork a day until his death. He made paintings that measured more than eight metres in length, such as the epic Le Cours des choses (The Way Things Go) in 1983, which was presented in the French pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1984. Increasingly abstract (although he always rejected this term), his works no longer contained any recognisable figures or objects, only intensive webs of twisting lines that referenced his continued fascination with graffiti – which harnessed the admiration of a younger generation of artists, including Jean-Michel Basquiat who regularly visited the Pace gallery in New York to see his work.

Jean Dubuffet, Mire G 177 (Bolero), 28 December 1983, Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

Jean Dubuffet, Mire G 177 (Bolero), 28 December 1983, Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

The last few months before his death in May 1985 were spent writing his autobiography – an ironic decision for an artist who instructed viewers to ‘trust my painting and not my writing’ while compiling a remarkable collection of instructions and directions on how to interpret his work. This paradox was at the heart of Dubuffet’s varied and revelatory career – that of an ‘amateur’ who became one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, notably by attempting to elevate and give a voice to materials and forms of art that had no name.

As he once said: 'For man, art is a great enchantment. Man's need for art is a totally primordial need, as much as and perhaps more so than his need for bread. Without bread, man dies of hunger, but without art he dies of boredom… However, think particularly about the arts that have no name: the art of speaking, the art of walking, the art of blowing cigarette-smoke gracefully or in an off-hand manner. The art of seduction. The art of dancing the waltz, the art of roasting a chicken.'

About

Jean Dubuffet : Brutal Beauty (17 May–22 Aug)

An exhibition celebrating French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), one of the most singular and provocative voices in postwar modern art.

Listen to our playlist