Music of conflict

Music has a unique role to play in war time. Dr Kate Kennedy looks at a number of solider-composers from World War I, from different backgrounds and nations, exploring the vital importance of music for survival.

The First World War is now remembered through its literature perhaps more than any other art form; we are all familiar with the traditional canon of war poets, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

However, we are considerably less familiar with the response of musicians to the war, both during and after the conflict. Here are a handful of composers from different sides, backgrounds and nations, who were caught up in the horror; some who survived, some who were less fortunate.

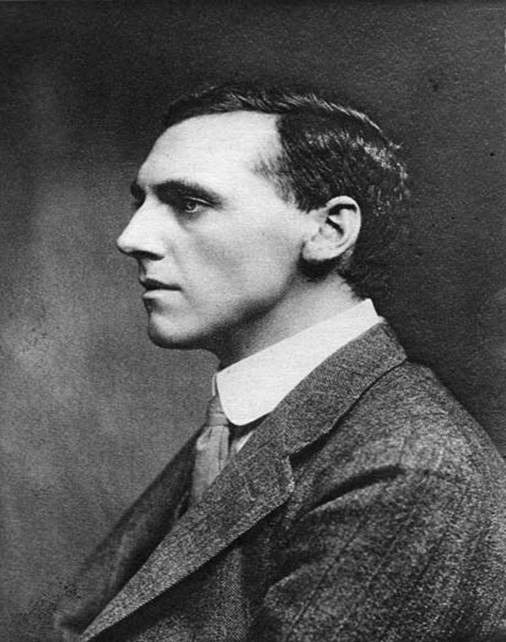

Ivor Gurney

(1890–1937)

Ivor Gurney was a student at the Royal College of Music when war broke out. He tried repeatedly to enlist, but was turned down because of his poor eye sight. However, in 1915 when the authorities had become less fussy, he joined the 2/5th Gloucesters, and after a long period of training spent 15 months in France and Belgium. He saw the very worst of the fighting around Ypres, and in the winter on the Somme.

When in trenches, it was easier to scribble down some lines of verse than it was to write a long piece of music, so he developed what would become a dual career as poet and composer, the poetry flowing ‘like buttermilk from a jug’. He did continue composing alongside his writing, and wrote a handful of songs at or near the front. All concern themselves, unsurprisingly, with death, or homesickness.

One of these, a seraphically beautiful miniature, sets his own words. It is a humble little note to the landscape of Gloucestershire that he loved dearly, not to forget him, as he fully expected not to return.

Gurney did return, gassed, and having previously been shot in the arm. His mental state was precarious, and what had been a pre-war tendency to depression and breakdown swiftly turned into something that we might now call schizophrenia or bi-polar disorder. He was incarcerated against his will in mental hospitals for fifteen years, desperately unhappy, and facing impending madness.

He continued to write, and with no future to anticipate, his verse and music returns to the trenches – he was perhaps the only war poet still writing about the minutiae of war experience well into the 1920s. His music became ever more harmonically experimental, and his music offered him an imaginative escape into a world of natural beauty that he would never see again.

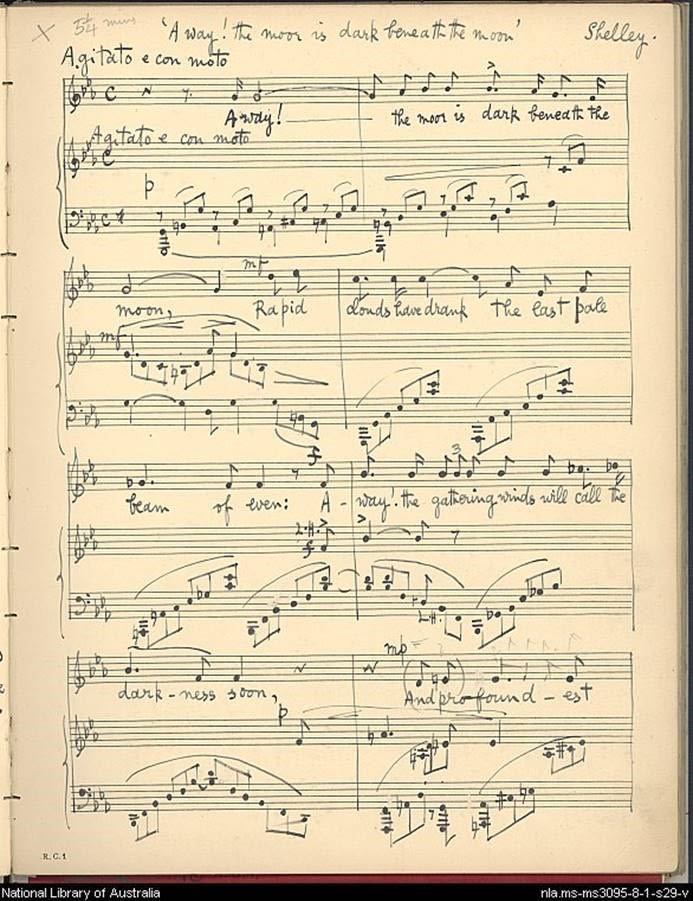

Frederick Septimus Kelly

(1881–1916)

F.S. Kelly was born to a very wealthy family in Sydney, Australia, and showed precocious musical talent from early childhood. He was sent to school at Eton, and then studied at Oxford. He was a formidably talented, driven man, who achieved near-legendary status as a rower, while also excelling as a concert pianist and composer. He won the Diamond Sculls three times and gold in the men’s eights at the London Olympics, but then decided that he would focus on his music. He studied in Frankfurt and gave recitals in Europe and Australia. His compositional style was European, with a blend of late romantic and more adventurous chromatic harmonies. His songs and piano works are dramatic, Wagnerian miniatures, powerful and craftsman-like.

Kelly was eager to volunteer when war was declared, and joined Winston Churchill’s newly formed Royal Naval Division in 1914. He travelled out to Gallipoli with a distinguished band of friends, including the composer William Denis Browne, the poet Rupert Brooke and Arthur Asquith, the Prime Minister’s son.

Rupert Brooke’s death en route moved Kelly deeply; he wrote his best-known composition Elegy for String Orchestra: In Memoriam Rupert Brooke immediately after he helped to bury his friend. Kelly went on to be wounded twice at Gallipoli and won the Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the evacuation. He sailed back alone from Gallipoli, leaving William Denis Browne lost for dead, and passing the beautiful Greek island of Skyros where the two composers had left Brooke. Kelly was killed fighting on the Somme in 1916. He left a Gallipoli violin sonata unfinished, which trails off poignantly as he ran out of time for composition. He was shot attempting to capture a machine gun emplacement.

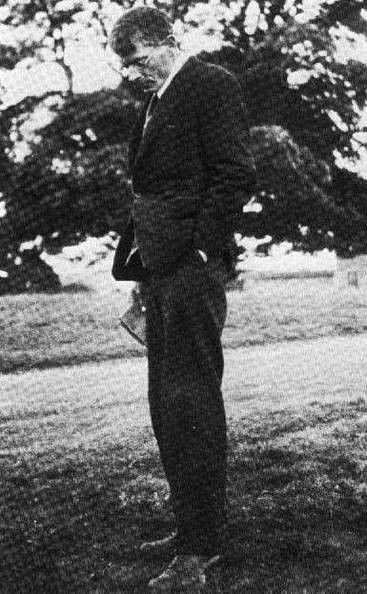

Rudi Stephan

(1887–1915)

Stephan was one of the most promising of the young generation of German composers caught up in the war. Like FS Kelly, he had also studied in Frankfurt, and then in Munich, which is where he had been living when the war broke out. In fact he was something of a parallel of Kelly’s, as both men were influenced by Stravinsky and by late romantic composers such as Richard Strauss. He wrote for orchestra and for string ensemble, works with intriguingly bland titles such as Music for Orchestra. This piece was his first real success, and his opera, Die Ersten Menschen would have been his second, had he lived to see it. He completed it just before the war began, but it was premiered in Frankfurt five years after he had died.

His music was uncompromising, and he insisted on no explanations, no stories or text being attached to his orchestral pieces. His opera, of course, has a plot; a provocative, Freudian re-telling of Biblical stories in which Eve is a nymphomaniac, and Cain’s murder an act of Oedipal jealousy. Stephan was a young man with determination and conviction, and a highly developed technical ability as a composer. He was sent to Galicia to fight on the Eastern Front, but was shot through the brain by a Russian sniper only two days after he had arrived.

He was 28 years old. Had he lived, his career would most certainly have been interesting, and uncompromising in his experimentation.

Photo: StadtWO M11270

Photo: StadtWO M11270

Photo: StadtWO M11263

Photo: StadtWO M11263

'His music was uncompromising, and he insisted on no explanations'

Ernest Macmillan

(1893–1973)

When war was declared on 4 August 1914, thousands of British men in Germany found themselves imprisoned in internment camps for the duration. Ernest Macmillan, a young student at the time, had been living in Germany, and had been imprisoned in solitary confinement. He was relieved to be moved to the Ruhleben internment camp in 1915, although the camp was never a comfortable place to be. It consisted of a hastily converted prison camp on the site of a racecourse, in the suburbs of Berlin. There was always the threat of conditions deteriorating – by 1916 the blockade of Germany was very effective, and there were calls for Germany to starve its internees to death, like hostages.

As Macmillan and other musicians waited to see what would become of them, they developed the camp into a microcosm of society – from a random collection of a few people to a fully functioning, civilised town. It had its own internationally admired postal system with its own stamps, which are now collector’s items. No work was required of the prisoners, no structure put in place – no link between them except nationality. It was a callous social experiment. Music and culture became the purpose, when there was no bigger purpose for living.

Accommodation was in horse boxes, six to a box, and in hay lofts above, with gabled roofs in which one can only stand straight in the centre. 100 men slept in each loft – luggage on feet, bodies touching at all times. Showers involved pouring icy water over oneself with a soup bowl, and in the winter it was terribly dark. Ernest Macmillan was obliged to compose clustered with the other men under the two light bulbs in the evenings.

During the four years, which, he found, did not pass quickly, Macmillan developed his skills as a conductor, with an orchestra on which he could practise daily, as well as studying composition with other more senior composers in the camp such as the Newcastle-based professor Edgar Bainton. By the end of the war he emerged with a doctorate conferred on him remotely by Oxford University for writing a large dramatic cantata that set a patriotic poem by Swinburne, England, an Ode. His career and outlook were profoundly affected by his time in the camp, and he developed his career in Canada driven by the conviction that music was essential to a civilised society’s psychological well being. His influence on Canadian music was so great that he became the only Canadian musician to be awarded a knighthood for his services to music.

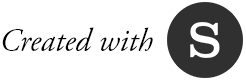

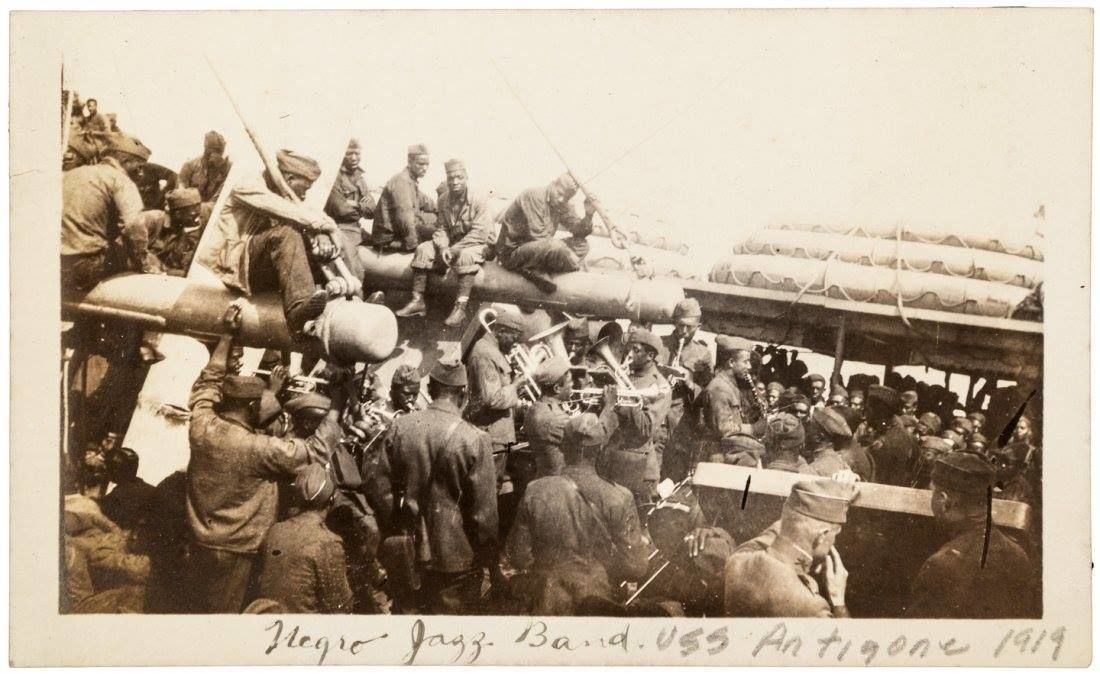

James Reese Europe

(1880–1919)

Jim Europe was an enormously influential figure, and one of the most popular bandleaders in America before the war. He was outspoken, and insisted on playing his own style of music, which shaped the early years of jazz. He said that ‘we have developed a kind of symphony music that, no matter what else you think, is different and distinctive, and that lends itself to the playing of the peculiar compositions of our race ... My success had come ... from a realisation of the advantages of sticking to the music of my own people.’

He achieved many firsts: he was the first black band leader to make recordings, and one of the first to be taken seriously as a professional musician. He was the first to perform with an African-American orchestra at the Carnegie Hall (in 1912), when the Hall had to suspend its rule of segregated seating, and he later became the first black officer to lead American soldiers into battle.

He had joined an Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard in 1916, before America had entered the war. It was a rare example of an organization in which black men could work together with white. That winter he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 15th Infantry Regiment of the National Guard, and when the US entered the war, his regiment, which was known as the Harlem Hellfighters joined one of only two black military divisions in the US Army that was allowed to fight.

Jim had trained as a machine gunner, but as he already had such a huge public following, was asked by the American Government to form a military band, which he named after his regimen. The Harlem Hellfighters regimental band travelled over 2,000 miles in France, performing for foreign dignitaries, wounded soldiers, troops on leave and French civilians. They were considered one of the best jazz bands in the world, and led the victory procession on their return to the USA after the armistice.

One of his musicians remarked: ‘who would think that little U.S.A. would ever give to the world a rhythm and melodies that, in the midst of such universal sorrow, would cause all students of music to yearn to learn how to play it? ....I sometimes think if the Kaiser ever heard a good syncopated melody he would not take himself so seriously’.

_______________________________________________________________

Jazz pianist Jason Moran explains why he’s reviving the music of Europe and his Harlem Hellfighters in his project James Reese Europe and the Absence of Ruin, culminating in a concert at the Barbican on Tuesday 30 October:

______________________________________________________________

On his return he recorded his band’s wartime hit On Parade in No Man’s Land, and began a tour of their wartime repertoire, by now the best-known African-American band master in the country. One night in May 1919, the Hellfighters performed in Boston. During a disagreement with one of his drummers in the interval, the man lunged at him with a pen knife. The cut seemed superficial, but the bleeding could not be stopped, and he died in hospital later that night. He had survived the trenches only to be killed in a scuffle in peacetime, and by a colleague. Thousands lined the streets of New York for his funeral, the first ever public funeral for an African-American.

Humanity through the arts

It is all too easy to assume that all composers involved in the war returned, if they did, to write the musical equivalent of the dissenting, officer-class poets we know so well. But not everyone’s experience of the war was characterized by the same anger and trauma that we find in poems by Owen and Sassoon. Musical responses to the war were as various as the men whom war affected. Gurney joined up hoping the routines of the army would cure his mental illness. Kelly, the consummate athlete and public school product, joined up because he was a natural army officer, bound by discipline and duty. Europe found an opportunity in enlisting to further the cause of early jazz, and raise the profile of black musicians. For Stephan it was simply a tragedy of a career cut short, but for Macmillan it was a four-year training opportunity, albeit under very difficult circumstances.

Through these men’s stories we can gain a sense of the complex relationship between war and music

Music has a unique role to play in wartime, in rallying troops, creating a sense of camaraderie and humanity in desperate circumstances, and in providing an outlet for the expression, both collective and private, of every emotion from despair to hope. Through these men’s stories we can gain a sense of the complex relationship between war and music; the vital importance of music for survival, and the reaffirming, again and again, of our humanity through the arts.

For the Fallen (4–11 Nov) looks to a future haunted and shaped by the past, with a series of concerts bridging the century between then and now.

On Spotify

About the author

Writer and broadcaster Dr Kate Kennedy is a Research Fellow at Wolfson College Oxford, and the Associate Director of the Oxford Centre for Life-writing. She has published widely on music, literature and the First World War, and is the author of the biography Ivor Gurney: Dweller in Shadows (forthcoming), editor of Literary Britten, and of The Silent Morning: Culture and the Armistice, 1918. She is the author of the play The Fateful Voyage, dramatising the story of Kelly, Browne and Brooke.