Exhibition Guide:

Noguchi

This exhibition explores the kaleidoscopic career of the Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988), one of the quintessential sculptors of the twentieth century.

Noguchi thought art should improve the way people live. Embracing social, environmental, and spiritual consciousness, he pioneered an expanded understanding of sculpture, which he knew could be: ‘a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness.’

The son of an Irish American mother and a Japanese father, Noguchi was born in Los Angeles, but spent his childhood in Japan. An American citizen of biracial heritage, he travelled around the world throughout his life, searching for a place where he felt he belonged: ‘With my double nationality and double upbringing, where was my home? Where my affections? Where my identity? Japan or America, either, both—or the world?’

Organised along interconnecting themes, this exhibition focuses on Noguchi as a global citizen and his risk-taking approach to sculpture as a living environment. An extraordinary range of sculptures in stone, ceramics, wood, and aluminium showcase his vast interdisciplinary output, from theatre sets to playground models, from landscape designs to furniture and lighting.

Reflecting on six decades of his practice, in which he consistently disregarded established hierarchies and the boundaries between disciplines, Noguchi stated in 1988 that ‘Art for me is something which teaches human beings how to become more human.’

Unless otherwise stated, all works are held in the collection of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York, and reproduction prints are from The Noguchi Museum Archives.

Room 1: I Became a Sculptor

Noguchi was trained in academic sculpture at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School in New York. He began his career making portrait heads. In 1926, he met Japanese dancer and choreographer Michio Itō. Noguchi designed masks for Itō’s Noh-inspired performance of At the Hawk’s Well by W.B. Yeats. Itō’s portrait in bronze commemorates Noguchi’s first performance-related commission.

A Guggenheim Fellowship paid for Noguchi to travel to Paris in 1927. His apprenticeship with modernist master-sculptor Constantin Brancusi changed Noguchi’s approach to art and introduced him to abstraction. In Brancusi’s studio, Noguchi cut wood and stone. He learnt the principle of truth to materials through the significance Brancusi attached to direct carving.

Rejecting the ideal of pure abstraction, Noguchi became interested in cellular structures, living organisms and the natural world. He experimented with metal sculpture, transforming industrial and everyday materials. Leda (1928) combined the dynamism of the Machine Age with the metamorphosis described in the Greek myth. The polished brass of Globular (1928) used reflections to expand the limits of the object.

The apprenticeship with Brancusi was to influence Noguchi throughout his career. Borrowing his Romanian mentor’s endless column motif, The Spirit’s Flight (1969) was Noguchi’s first use of post-tensioned marble. It explored the effect of the spiral on a geometrical column: ‘The result is an effect of aliveness. As is well known, all nature tends to the helix — from the flow of water, to wind, tropical storms, or the flow of blood.’

Room 2 - Sculpting Space

After Paris, Noguchi travelled to London, Moscow, Beijing, Tokyo and Kyoto between 1928 and 1931. At the British Library in London, he read up on Asian philosophies, art and religions. In 1930, Noguchi learnt traditional ink-brush technique in Beijing with Chinese painter Qi Baishi. He concluded from his experience that ‘all Japanese art has roots in China’.

He reflected on his global explorations as a process of ‘selfdiscovery’: ‘I had to know my own identity and continuity.’ Boy Looking through Legs (Morning Exercises) (1933) is a self-portrait of the artist looking at the world upside down through his translucid blue eyes. His portrait sculptures helped him to survive financially, a further aspect of his global network and an expression of his skill across a variety of sculptural media.

His unrealised New York playground Play Mountain (1933) was a first attempt to ‘break out of the categories of sculpture’. Using no apparatus, Noguchi instead shaped the ground with steps and slopes. He saw this work as ‘the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth. It is also the progenitor of playgrounds as sculptural landscapes.’ In a similar way, for Frontier (1935)—his first collaboration with choreographer Martha Graham—Noguchi hung a rope from two top corners of the stage with a fence at the centre: ‘I thought of space as a volume to be treated sculpturally and the void of theatre space as an integral part of form and action.’

Room 3 - Expanding Universe

Noguchi’s belief in the humanist value of science and technology was influenced by his encounter with architect and inventor R. Buckminster Fuller in 1929. He made a bronze bust of his new friend—plated with shiny chrome, a new material used in automobile manufacturing. One of Noguchi’s earliest commercial designs, the baby monitor Radio Nurse (1937), was made in Bakelite, the first synthetic plastic.

Noguchi shared Fuller’s ideal of the ‘American dream of material progress’. Their earliest collaboration was the model for Fuller’s Dymaxion Car (1932–33), a prototype vehicle designed to travel on land, on sea and in the air. Its aerodynamic curves recalled Noguchi’s Miss Expanding Universe (1932). Suspended from the ceiling, the cast aluminium figure seemed to soar like a plane. Inspired by Hubble’s law on the unfixed, expanding nature of the universe, the sculpture expressed Noguchi’s love for the dancer and choreographer Ruth Page. He designed a dress for her whose stretched cloth extended the sculptural possibilities of body weight, mass and gravity. Similarly, Noguchi’s Spider Dress for Martha Graham’s dance of collapse and levitation in Cave of the Heart (1946) used brass wire to expand the physical boundaries of the human body, like radiating sunbeams.

From the cosmic scale of the universe evoked by the satellite-in-orbit wall sculpture Bucky (1943) to the microscopic division of the cell depicted in Mitosis (1962), Noguchi looked to the primordial forms and geometric structures underlying nature for inspiration.

Room 4 - Political Conscience

Reflecting his continued scepticism of the idea of pure abstract sculpture, Noguchi created the anti-fascist mural History Mexico (1936) in Mexico City. He wanted to start making public work that ‘deals with today’s problems’. Set between the triumphant clenched fist of the worker and iconographic depictions of capitalism, fascism and war, Einstein’s formula E=mc2 was engraved on the mural as a symbol of scientific knowledge and hope for the future.

Reflecting his ambition to produce socially engaged work, Noguchi’s 1935 solo exhibition at the Marie Harriman Gallery presented a number of projects that engaged with American identity, labour and remembrance. Death (Lynched Figure) (1934) was based on a published photograph of the lynching of a black man named George Hughes in Sherman, Texas in 1930. Describing the work as a form of ‘social protest’, Noguchi participated in two important anti-lynching exhibitions organised to end the horrific practice.

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on 7 December 1941, American President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorising the imposition of martial law, which led to the forced imprisonment of Japanese citizens and American citizens of Japanese heritage living in the western United States. Even though Noguchi was exempt as a New York resident, he chose to enter one of the largest camps, in Poston, Arizona. There he aimed to create an arts and recreation centre with a programme intended to improve the lives of the prisoners: ‘I was no longer the sculptor alone. I was not just American but nisei. A Japanese-American.’

Room 5 - Lunar

Noguchi’s experience of voluntary internment in Poston War Relocation Center had a significant impact on much of his practice during the Second World War, particularly his series of works called ‘Lunars’. A dominant motif in these is the barren landscape of the Arizona desert, comparable to the surface of the moon, and described by Noguchi in a letter to Man Ray as ‘like in a dream’.

My Arizona (1943) conveys Noguchi’s isolation and inner turmoil, its title suggesting a subjective world with threatening protrusions and craters. The title Yellow Landscape (1943) may be a direct reference to the pervasive racist terminology and the prejudice towards Asian-Americans throughout the United States during the 1940s. Of the ‘intense dry heat’ at Poston, Noguchi said ‘maybe it’s the weather that makes everything so unreal’. His ‘Lunars’ series featured light-emitting electrical components, as seen in Lunar Infant (1944), a biomorphic form suspended within an ominous enclosure. Noguchi’s use of vivid colour in Red Lunar Fist (1944) creates a similar effect of blazing heat, and simultaneously suggests an aggressive gesture and an embrace.

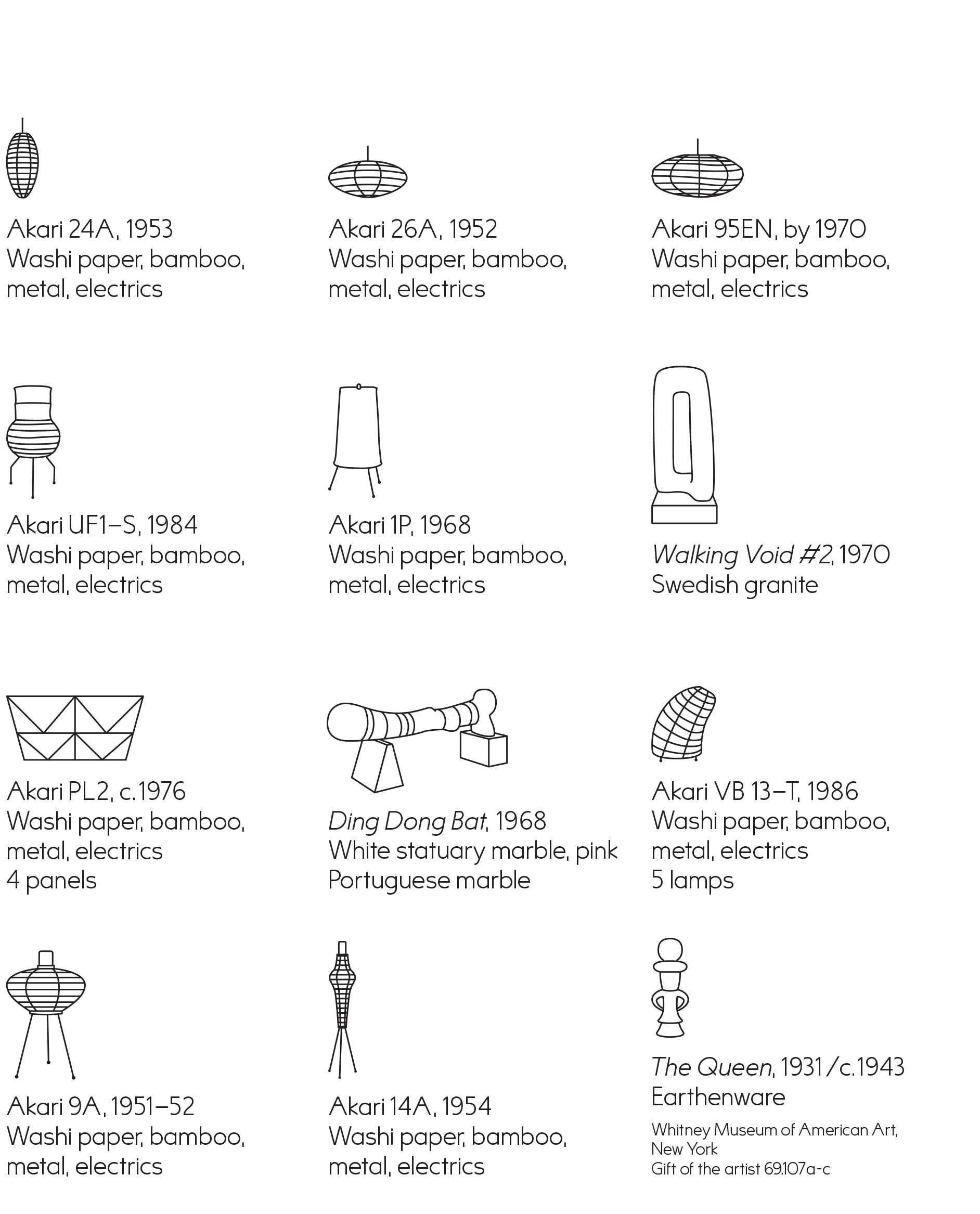

These self-illuminating works anticipate Noguchi’s creation of Akari light sculptures in 1951—akari means ‘light’ in Japanese, encompassing both illumination and weightlessness. They show his combination of tradition with modern technology, using electric bulbs, and brought sculpture to everyday households, in line with the artist’s democratic commitment to accessible public art.

Room 6 - Landscape of the Mind

Noguchi refined his interest in the lunar landscape in sculptures such as Double Red Mountain (1969), in which his use of red Persian travertine and reduced abstract forms created an evocative dream-like space: ‘My works in this vein are landscapes really, a sculpture of the whole, not an assemblage of parts or props, as with the theatre. High, low, horizontal, or vertical, they are a landscape of the mind.’ The form of Double Red Mountain recalled the mesas Noguchi had observed in the Arizona desert.

When Noguchi came back to New York, he returned to direct carving and created Time Lock (1944–45): ‘These straight carvings were to me the sure things of sculpture, long-lasting (locked against time’s erosion), sculptural sculpture.’ The white and pink veins of the Languedoc marble made it look like the planet Jupiter. Noguchi believed in sculpture’s ability to capture the geological timescale of the universe: ‘All I do is provide an invasion of a different time element into the time of nature.’ Einsteinian physics and its fluid concept of time had a profound influence on Noguchi and the Surrealists. Time Lock was exhibited in ‘Le Surréalisme en 1947’ exhibition at Galerie Maeght in Paris.

While he was in New York, Noguchi’s participation in The Imagery of Chess (1944–45), curated by Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst at Julien Levy Gallery, brought him together with a number of artists living in exile. The portable, nomadic nature of the chess set became a paradigm of wartime sculpture.

Room 7 - Skin and Bones

In a civilisation devastated by the atrocities of the Second World War, Noguchi contributed to a global reconfiguration of the role of the artist as searching for a new foundation for culture. The World is a Foxhole (1942–43) expressed his wartime anxiety: ‘ The thoughts of a soldier in a foxhole: a red rag atop a pole —a signal of hope and despair.’

Based on an image of a bomb site in the African desert and cast in bronze, This Tortured Earth (1942–43) was a precursor to the land art of the 1960s and ’70s. It offered a view of the earth from above ‘to memorialise the tragedy of war. There is injury to the earth itself. The war machine, I thought, would be excellent equipment for sculpture, to bomb it into existence.’

During the 1940s, Noguchi also created innovative interlocking sculptures made from thin slabs of stone prepared for building façades. The multiple parts were held together only by gravity, in a manner similar to the joinery techniques used in Japanese houses that Noguchi had learned in his youth. The title Humpty Dumpty (1946) evoked the nursery rhyme, with Humpty Dumpty’s ‘great fall’ serving as an existential metaphor for the war. A year later, the sensuous tonality of the thin slabs of Georgia marble in Avatar (1947) created a precarious and harmonious composition that seems both masculine and feminine, erotic and violent.

Room 8 - Gravity

Noguchi confronted the devastating impact of the atomic bomb during a visit to Hiroshima in 1951. Attempting to define the role of the artist in the Atomic Age, he questioned the social purpose of sculpture: ‘The tragic aftermath of two wars is a moral crisis from which there is no succour for the spirit… now there is only mechanisation and the concepts of power.’

An important development of Noguchi’s biomorphic interlocking sculptures, Cronos (1947) draws on classical myth, and is a highlight of his exploration of humanity’s capacity for violence and of the destruction brought by the Second World War. The multiple parts suspended in the centre of the work depict Cronos swallowing his own children. The work was completed in 1947, the year Noguchi’s father — the poet Yonejirō Noguchi — died. The suspended elements also recall — like his Mortality (1959) —a clock pendulum, and thus the idea of passing time: ‘Our pendulous and precarious existence is shaped by gravity.’

The arched form of Cronos echoed Noguchi’s unrealised 1952 design for a monument to the dead of Hiroshima, allegedly rejected in light of his American citizenship. Underneath the arch, Noguchi would have placed ‘the names of the world’s first atomic dead’. Another symbol of Hiroshima’s tragedy, the Noh-inspired mask Okame (1954) was described by the artist as ‘all bandaged up with one pathetic eye and no longer humorous’.

Room 9 - Earth

Noguchi’s unrealised land art project Sculpture to be Seen from Mars (1947) imagined a human figure drawn on the surface of the abandoned Earth so as to be seen from afar by a non-human species. This monument to extinct humanity mirrored the devastated landscapes of the post-atomic world.

The ceramics Noguchi produced on his return to Japan in 1950 demonstrated his innovative approach to craft techniques. His apparent turn back to tradition actually served as a search for a ‘common humanity’, for a future beyond nationalities: ‘An innocent synthesis must rise from the embers of the past.’ Noguchi only ever created ceramics in Japan, stating: ‘I think the earth here and the sentiment here are suited to pottery.’ The artist felt a similar impulse when making The Queen in 1931, the year he encountered Haniwa funerary figures while studying ceramics in Kyoto with Jinmatsu Uno: ‘they were in a sense modern, they spoke to me and were closer to my feeling for earth’.

Noguchi felt he belonged to the past and the future: ‘To be modern means nothing to me. Ultimately, I like to think, when you get to the furthest point of technology, when you get to outer space, what do you find to bring back? Rocks!’ He observed the placement of rocks in Japanese gardens and astronomical instruments in observatories. He made sculptures that ‘emerge from the earth’, positioning human beings in relation to the floor, which he regarded as ‘our platform to humanity, as the Japanese well know’.

Room 10 - New Nature

Named after the first nuclear test detonation, which took place in 1945 in the New Mexico desert, the multi-angled figure Trinity gets right to the heart of nuclear fission, an atom split into smaller nuclei. Over the years, Noguchi became highly critical of the impact of technological advances: ‘If the world would wait blowing up, I wanted to find out what sculpture had once been, to what purpose, to what end, to what it might again aspire to in a world in flux.’

The artist developed a deep appreciation for carving hard stone, such as basalt and granite. As with the growth of trees, Noguchi saw time as integral to the process, exploring the transformation of rock through various states. He drilled a hole into The Inner Stone (1973) using a rotating pipe, and made a modern tsukubai — a ritual waterbasin found in Japanese gardens — with power tools.

By contrast, the weightless, gravity-defying steel and glass skyscrapers of New York inspired the aluminium sculptures Noguchi made from 1958, in collaboration with the workshop of Edison Price. Without any welding or fastening techniques, aluminium sheets were bent into continuous folds, like the paper of an Akari light or of origami: ‘I wanted to deny weight and substance.’ Noguchi conceived of sculpture as an ecosystem of dynamic forces affecting each other, as in nature’s own structure: ‘opposites come together. Stone is depth, metal the mirror. They do not conflict.’

Room 11 - Civic Sculpture

Noguchi created total environments designed to enrich the lives of those who engaged with them. In his early career his ambitious public projects were often rejected, but later on he was able to produce large-scale sculptural landscapes, inspired by his travels around the world. His environments reflected the ceremonial function of sculpture in gardens he saw in Japan, and in religious and cultural sites all over the world, exploring a sense of spiritual connection between humanity and the Earth. Noguchi compared the orchestration of gardens to his experience of making stage sets for theatre: ‘I like to think of gardens as a structuring of space.’

In 1956, Noguchi created the gardens for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, transporting large stones from Shikoku and Okayama in Japan. He composed formations of rocks, ponds and plantings in dialogue with the Brutalist architecture of Marcel Breuer. For the Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, New York (1961–64) — a water garden in a circular well — he used black rocks from the Uji River, near Kyoto: ‘I considered this my Ryoanji — that most famous rock garden in Japan.’ In 1970, Noguchi collaborated with architect Shoji Sadao on large-scale futuristic fountains with cascading water for the Expo ’70 World Fair in Osaka.

Noguchi considered play a critical application of his commitment to sculpture’s social and civic role. In 1975, he completed a ‘playscape’ in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park — his first and only in the US— drawing on science and educational theory to develop play equipment that is still used by the public today.

Monitors 1-8

1: UNESCO Gardens, Paris, 1956–58

Gardens for UNESCO, Paris, France, by Arnold Eagle, c. 1970; Isamu Noguchi interviewed at Henraux in Querceta, Italy. Gardens for UNESCO, Paris, France; Isamu Noguchi documentary produced by Bruce Bassett and Whitgate Productions, 1980; Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World, 1973, by Arnold Eagle

2: The Billy Rose Art Garden, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1960–65

The Billy Rose Art Garden at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Israel, by Arnold Eagle, c. 1970; Isamu Noguchi interviewed at IBM Headquarters, Armonk, NY, by Arnold Eagle, c. 1971; Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World, 1973, by Arnold Eagle

3: Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, New York, 1961–64

Isamu Noguchi working at his studio in Mure, Japan. Red Cube. c. 1970; Isamu Noguchi documentary produced by Bruce Bassett and Whitgate Productions, 1980; Isamu Noguchi exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Footage of Red Cube, 140 Broadway, New York and Sunken Garden, Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, New York. c. 1970; Isamu Noguchi interviewed at IBM Headquarters, Armonk, NY, 1971; Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World, 1973, by Arnold Eagle

4: IBM World Headquarters, Armonk, New York, 1964

Gardens at IBM Headquarters, Armonk, NY

5: Octetra, 1965–66

Unedited footage of Isamu Noguchi in Spoleto, Italy, sent to Noguchi from Dimitri

Hadzi, 1968; Isamu Noguchi exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Footage of Red Cube, 140 Broadway, New York and Sunken Garden, Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, New York, c. 1970; Isamu Noguchi documentary produced by Bruce Bassett and Whitgate Productions, 1980; Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World, 1973, by Arnold Eagle

6: Expo ’70, Osaka, Japan, 1970

Expo ‘70 fountains at Japan’s World Fair in Suita, Osaka, Japan, 1970; Daytime footage of Expo ‘70 fountains at Japan’s World Fair in Suita, Osaka, Japan, c. 1970; Isamu Noguchi looking at his Expo ‘70 fountains with a group at Japan’s World Fair in Suita, Osaka, Japan, c. 1970; Night footage of Expo ‘70 fountains, Japan’s World Fair in Suita, Osaka, Japan, 1970; Isamu Noguchi documentary produced by Bruce Bassett and Whitgate Productions, 1980; Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World, 1973, by Arnold Eagle

7: Piedmont Park, Atlanta, Georgia, 1975–76

Isamu Noguchi documentary produced by Bruce Bassett and Whitgate Productions, 1980

8: Philip A. Hart Plaza, Detroit, Michigan, 1972–1979

Isamu Noguchi documentary produced by Bruce Bassett and Whitgate Productions, 1980

Room 12 - Citizens of Earth

In 1949 Noguchi embarked on a period of research across Europe and Asia. He began a study of ancient civilisations, visiting heritage sites in England, France, Italy, Spain, Greece and Egypt, and also travelling throughout India, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal and Japan. He took photographs of how people interacted with civic spaces and sacred sites, from the stones of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England, to the fire-lookout towers in Hiroshima, Japan. He wanted to learn how to integrate sculpture into established cultural traditions while embracing modern technology.

The architectural instruments of the eighteenth-century Jantar Mantar astronomical observatory in northern India inspired the marble sun, cube and pyramid of Noguchi’s Sunken Garden (1960–64) at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. His unrealised ‘lunar garden’ for Expo ’70 in Osaka would have included his Octetra play sculpture. Noguchi’s playground elements often refer to geometry and science, in particular triangulated structures such as the tetrahedron, which R. Buckminster Fuller conceived as ‘a minimum structural system of the Universe’.

Noguchi wanted to ‘bring sculpture into a more direct involvement with the common experience of living’. To this end, he used his collection of West African furniture to study the technology that made objects function. Inspired by a Lega market stool from what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rocking Stool in Wire Form (1954) was designed, as LIFE magazine commented at the time, to allow ‘fidgety sitters to tilt, rock back and forth, and even spin around with a fair chance of not tipping over.’

Explore Noguchi

Catalogue

A richly illustrated monograph published by Prestel, including essays by Rita Kersting, Nana Tazuke-Steiniger, Florence Ostende, Fabienne Eggelhöfer, Dakin Hart, alongside a conversation chaired by Devika Singh with Karen L. Ishizuka, Katy Siegel and Danh Vo. A fully illustrated chronology details the entirety of Noguchi’s career. Available at the Barbican Shop and online.

Discover

Learn more about Isamu Noguchi's life, work, and legacy in our online collection which will feature articles, videos, tours, and more, throughout the exhibition.

Organised and curated by Barbican (London), Museum Ludwig (Cologne) and Zentrum Paul Klee (Bern), in partnership with LaM— Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut.

This exhibition would not have been possible without the collaboration of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York.

Noguchi is curated at Barbican by Florence Ostende.