Soheila Sokhanvari:

Rebel Rebel

Exhibition Guide

Rebel Rebel

When Roohangiz Saminejad starred in The Lor Girl (1932), the first Persian ‘talkie’, the film had to be shot in Bombay because it was too controversial for an Iranian woman to appear in public without a veil. The film was a huge box office hit but Saminejad suffered terrible harassment; she later changed her name and lived the rest of her life in anonymity.

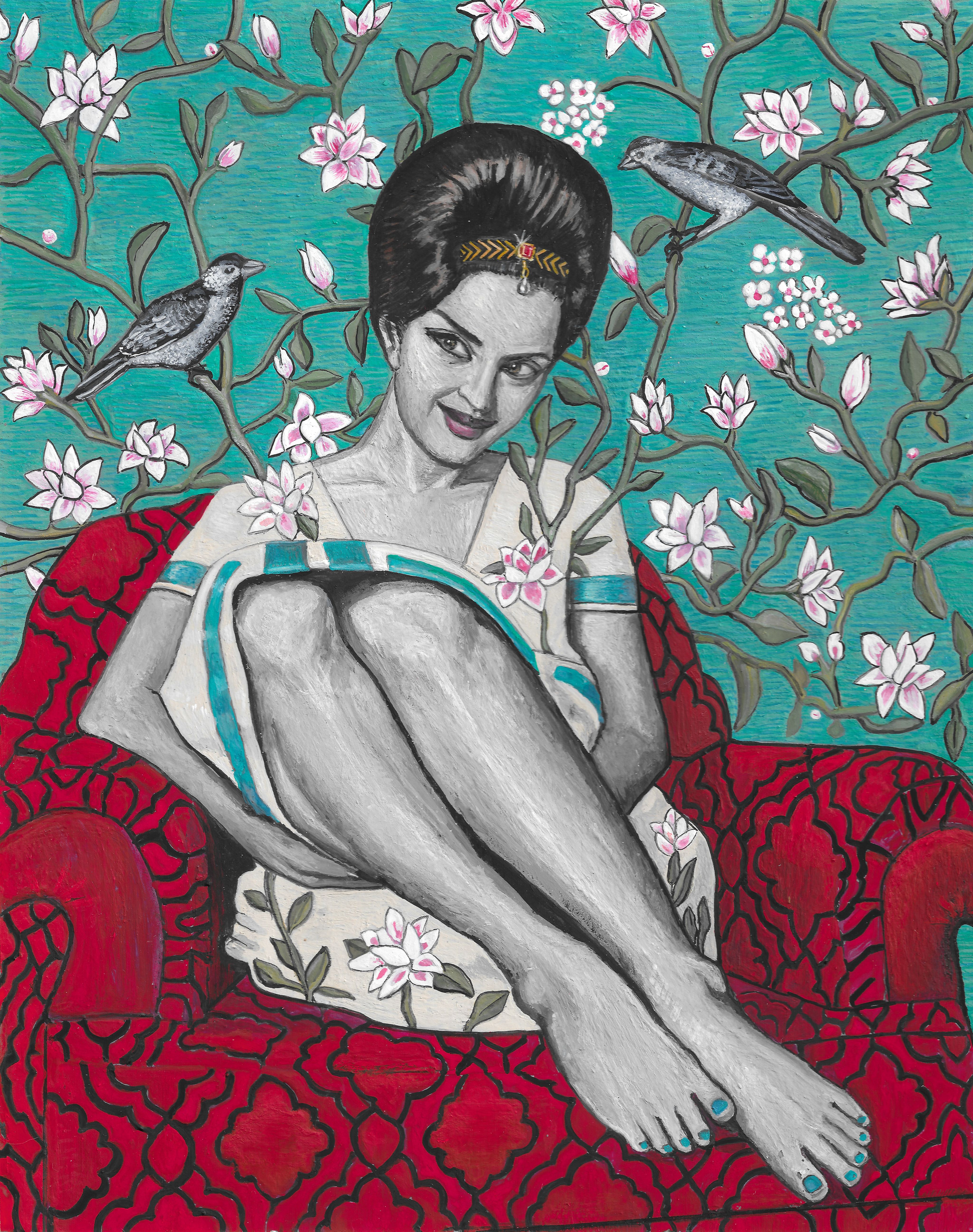

At the Barbican, she is the first of 28 women depicted by Soheila Sokhanvari in jewel-like miniatures. Each is a labour of love: painted onto calf vellum with a squirrel-hair brush, using the ancient technique of egg tempera. These works are set against epic, hand-painted murals along the 90-metre wall that reference traditional Islamic patterns, designed to dizzy the beholder so that they could contemplate the vastness of the universe and the greatness of God. As you pass Sokhanvari’s mirrored monolith, based on the mysterious form in Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi classic 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), you enter a world in which painting, sculpture and sound combine to induce an equivalent kind of feminist delirium.

Borrowing from David Bowie’s 1974 cult pop song, Rebel Rebel pays tribute to the extraordinary courage of these female stars – who pursued their careers in a culture enamoured with Western style but not its sexual freedoms – and laments their fate, after the revolution in 1979 left them with a stark choice: renounce any role in public life or be forced into exile. The soundscape, which weaves together the voices of iconic performers including Googoosh and Ramesh, is especially poignant since it remains illegal in Iran for a woman to sing in public. Sokhanvari herself fled to the UK as a child, a year before the Pahlavi regime was overthrown; now a studio artist at Wysing Arts Centre, she works every day on representing poetically the complexities of life in pre-Revolutionary Iran.

In loving memory of Ali-Mohammed Sokhanvari (1927-2021)

For more information about the women honoured in this installation, read on.

List of Works

1 Monolith, 2022, wood, metal, perspex mirrors and glitter.

2 The Lor Girl (Portrait of Roohangiz Saminejad), 2022, egg tempera on parchment.

3 Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season (Portrait of Forough Farrokhzad), 2022, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

4 Mahvash (Portrait of Mahvash), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum.

5 Only the Sound Remains (Portrait of Ramesh), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, J&A Private collection.

6 Rebel (Portrait of Zinat Moadab), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Elizabeth and Jeff Louis.

7 A Persian Requiem (Portrait of Simin Daneshvar), 2020, egg tempera on calf vellum.

8 The Beloved (Portrait of Molouk Zarabi), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

9 Cosmic Dancers I (Hologram), 2022, wood, metal, PVA, acrylic sheet, car paint, emulsion paint and electronics.

10 Wild at Heart (Portrait of Pouran Shapoori), 2019, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Marwa R. Al Khalifa.

11 She Walks in Beauty (Portrait of Shohreh Aghdashloo), 2022, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Aarti Lohi.

12 Still, I Rise (Portrait of Shahla Riahi), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

13 You Don't Own Me (Portrait of Irene Zazians), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection, Hong Kong.

14 The Love Addict (Portraits of Googoosh), 2019, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

15 Eve (Portrait of Katayoun (Amir Ebrahimi)), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

16 A Dream Deferred (Portrait of Haydeh Changizian), 2022, egg tempera, 23.5 ct gold on calf vellum, private collection.

17 The Voice Within (Portrait of Soosan), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Maren & Leonard Lansink, Berlin.

18 Cosmic Dancers II (Hologram), 2022, wood, metal, PVA, acrylic sheet, car paint, emulsion paint and electronics.

19 Desiderium (Portrait of Fakhri Khorvash), 2020, egg tempera on calf vellum.

20 Tobeh (Portrait of Zari Khoshkam), 2020, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Kristin Hjellegjerde.

21 Anarchy of Silence (Portrait of Azar Shiva), 2022, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

22 Rhapsody of Innocence (Portrait of Monir Vakili), 2022, egg tempera and 23.5 ct gold on calf vellum.

23 Without You (Portrait of Jaleh Sam), 2020, egg tempera on calf vellum, private collection.

24 The Immortal Beloved (Portrait of Pouri Banaaei), 2022, egg tempera on calf vellum.

25 Hey Baby. I'm a Star (Portrait of Forouzan), 2019, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Susan Dunn.

26 The Dancing Queen (Portrait of Jamileh), 2019, egg tempera on calf vellum, courtesy of Dangxia Foundation, China.

27 Memories of You (Portrait of Delkash), 2019, egg tempera on calf vellum.

28 Bang (Portrait of Faranak Mirghahari), 2019, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Elizabeth and Jeff Louis.

29 The Woman in the Mirror (Portrait of Fereshteh Jenabi), 2021, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of the Hundle Family.

30 Kobra (Portrait of Kobra Saeedi), 2022, egg tempera on calf vellum, collection of Jim and Irene Karp.

31 Baptism of Fire (Portrait of Nosrat Partovi), 2022, egg tempera on calf vellum.

32 The Star, 2022, perspex two-way mirrors, wood, metal, plastic and electronics.

Unless otherwise stated, all works are courtesy of the artist and Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery.

Portrait Biographies

Research by Tobi Alexandra Falade, Hilary Floe and Soheila Sokhanvari

Roohangiz Saminejad

1916-1997

2 The Lor Girl (Portrait of Roohangiz Saminejad), 2022

Saminejad was an actor who became famed as the first female lead in an Iranian ’talkie’ film, playing the role of Golnar in The Lor Girl in 1933. Still in her teens, it was filmed in Bombay (present-day Mumbai), because it was still taboo for a woman in Iran to appear without a veil in public. Saminejad’s heroic character works as a maid in a teahouse; she falls in love with a government agent, rides a horse, escapes bandits, and rescues her lover. The film was a huge success, and Saminejad went on to star in the romantic drama Shirin and Farhad the following year. However, the conservative culture of the time meant that she was harassed and excluded for her work in the film industry; to escape her notoriety, she changed her name and chose to live in anonymity for the rest of her life. 45 years after The Lor Girl, the Islamic revolution in 1979 led to a dramatic rollback of women’s legal rights under right-wing theocratic leadership. But in a late interview, Saminejad remembered that even before 1979, ‘everyone wanted to kill you because a Muslim woman didn’t have the right to act. To step out of the studio we needed three bodyguards. What can I say? That’s why I let go of acting’.

Forough Farrokhzad

1934-1967

3 Let us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season (Portrait of Forough Farrokhzad), 2022

Farrokhzad was one of Iran’s greatest modernist writers, whose poetry often dealt with the subject of female desire. She was born into a middle-class family in Tehran, shortly before the pro-Western Iranian king, Reza Shah, passed a law banning the female veil and women were allowed into schools and universities. Society, however, remained strongly patriarchal. Her poem Sin, written in 1954 at the age of nineteen, was considered scandalous for its unapologetic confession of infidelity: ‘I have sinned a rapturous sin / in a warm enflamed embrace’. When she divorced her husband, not long after publishing this poem in the periodical Roshanfekr (The Intellectual), she lost custody of their young son, Kamyar. This trauma led to a nervous breakdown and she was admitted to a psychiatric unit, where she was subjected to electroshock treatment. For Farrokhzad, writing was both personal and political: in the forward to her first poetry book in 1955, she wrote of trying to ‘break the shackles binding women’s hands and feet.’ In 1961, she became one of Iran’s first female film directors with her poetic documentary The House is Black, about Iranians with leprosy. Farrokhzad died tragically young at the age of 32 in a car accident. After the Islamic revolution in 1979, her poetry was banned for over a decade and many extracts remain censored to this day.

Mahvash

1933-1961

4 Mahvash (Portrait of Mavash), 2021

Mahvash (born Masoumeh Azizi Borujerdi) was one of the most beloved singers and cabaret performers of mid-century Iran. As a little girl, she moved to Tehran with her family, including her mother Fatemeh, who played the tar, an Iranian lute. From singing and dancing for her parents as a child, she made her way into Tehran’s cabarets and cafes. Often donning costumes in keeping with the characters she portrayed in her vibrant songs, she invited predominantly working-class audiences to sing along with her.

From 1954, Mahvash shot to national fame through cinema appearances. With her combination of sweetness and sex appeal, her song-and-dance performances were so popular that they were even introduced into Gary Cooper and John Wayne films when screened in Iran. She was also fabled for her extensive philanthropy. However, her popularity could also be used against her: in 1957 a book titled Secrets of Sexual Fulfilment was published under her name but without her consent, illustrated with pin-up-style photographs.

Mahvash died tragically young in a car accident, not yet thirty. Initially, given her career as a performer, the conservative religious authorities refused to allow her body to be buried in a Muslim cemetery. Given the scale of public grief following her death, they relented, and hundreds of thousands of mourners reportedly gathered in the streets to bid her farewell.

Ramesh

1946-2020

5 Only the Sound Remains (Portrait of Ramesh), 2021

Ramesh (born Azar Mohebbi Tehrani) was an iconic singer during the golden age of Persian pop music. Her family allowed her to pursue a career in music and in 1964, aged only 14, she performed for the first time on a classical radio programme. As her career developed, she fused Persian and Azerbaijani musical sounds with those borrowed from Western jazz and rock, producing numerous hits in the 1960s and 1970s. Ramesh left Iran after the Islamic revolution in 1979, which enforced mandatory veiling and prohibited women from singing in public in front of men. Ramesh refused to perform under these restrictions and lived the rest of her life in exile in the US, commenting that ‘if one day I return to Iran, I will sing from the bottom of my heart for my people.’ She died in Los Angeles in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Zinat Moadab

1923–

6 Rebel (Portrait of Zinat Moadab), 2021

By the time the young Zinat Moadab starred in the first ‘talkie’ made in Iran, she had already experienced hardship. Aged only fourteen, she was forced into an arranged marriage to a man 30 years her senior. She divorced at seventeen, but as a divorcee she was not considered fully respectable in polite society and was unable to return to school. When director Esmail Koushan offered her the lead role in his ground-breaking film The Storm of Life (1948), she did not tell her conservative family about her new career. The film was critical of the practice of arranged marriage and although the premiere was attended by royalty, Moadab’s family responded badly when they discovered her participation. An older half-brother, who had never met her, was so enraged by Moadab’s perceived immodesty that he made repeated attempts on her life. Undeterred, she acted in several more films but also ventured into a career at Koushan’s studio, becoming the first Iranian woman to edit films as well as doing voiceover work and studio management. She also enjoyed a seventeen-year career on the radio as a broadcaster and actor. She married the dissident journalist, writer and filmmaker Parviz Khatibi, with whom she had three children. In 1973, Moadab and her husband moved to the US in protest against the Shah’s regime. After the 1979 revolution, they created and performed in the first weekly radio program in Farsi in New York. In the US, Moadab remained active in the theatre – acting, directing, and designing sets and costumes. She lives today in Los Angeles.

Simin Daneshvar

1921-2012

7 A Persian Requiem (Portrait of Simin Daneshvar), 2020

Writer and academic Simin Daneshvar was a literary pioneer, becoming in 1948 the first female fiction writer in Iran to be published under her own name. Born to a family of middle-class intellectuals in Shiraz, she was educated by British missionaries; it was a formative exposure to Western colonialism that would shape her writing and thinking. After gaining her doctorate in 1950 at Tehran University, she spent two years in California on a Fulbright Scholarship at Stanford before returning to lecture in art history at the university until 1981. Despite her academic career and her distinguished work as a literary translator, it is her bestselling fiction for which she is largely remembered. Daneshvar’s novels and short stories addressed Iran’s turbulent recent history through a focus on the lives of women. Her most famous novel, Savushun (A Persian Requiem), 1969, depicts Shiraz in the 1940s during the devastating British occupation. Its heroine, Zari, protests against the destructive actions of the occupying army with an enduring cry: ‘I wish the world was run by women. Women who have given birth and know the value of their creation. They know the value of endurance, patience and monotony and not being able to do anything for themselves … if the world was run by women, there would be no wars.’ Daneshvar died in 2012 after a bout of influenza; she was buried in Behesht-e Zahra in Tehran after a request for burial with her husband in the Firouzabadi mosque was denied.

Molouk Zarabi

1910–1999

8 The Beloved (Portrait of Molouk Zarabi), 2021

Molouk Zarabi (born Mouluk Faršforuš Kāšāni) was a popular classical singer and tombak player. Her grandfather had been a singer at the court of the Nāṣer-al-Din Shah (1848-96) and Zarabi was musically precocious, first performing in public at the age of thirteen, despite her family’s disapproval. Her mastery of the tombak, a traditional Iranian goblet drum, led to her adopting the stage name Zarabi, derived from the word żarbi which refers to rhythmic, percussive compositions. In addition to high-profile theatre and cinema performances, she had a long association with Radio Tehran, which broadcast her voice across the country.

Music in Iran could be politically charged, and in 1927 Zarabi recorded the protest song Morgh-e Sahar (The Bird of Dawn). Its controversial lyrics, (‘Oh, caged bird / get out of the cage / And start singing for the freedom of mankind’), saw part of the song banned during the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1925-41) for fear that it might encourage dissident thinking. With her deep, mournful vocals, Zarabi’s famous rendition became a lasting symbol of resistance. Like all Iranian women, she was banned from singing after the 1979 revolution and fell silent. She died in 1999 and is buried in Tehran.

Pouran Shapoori

1934-1990

10 Wild at Heart (Portrait of Pouran Shapoori), 2019

Pouran (born Farhdokht Abbasi Taghany), one of Iran’s most famous pop stars, came from a wealthy and conservative Muslim family. Her childhood dreams of being a singer conflicted with her family’s goals for her. After moving to Tehran, she was supported by an aunt – Roohbakhsh, herself a prominent singer – and pursued musical studies. Despite her aunt’s success, her fears for her reputation as a female performer led her to appear under a series of assumed names. Rising to fame on Radio Tehran in the 1950s, she was initially known simply as ‘Anonymous Lady’. When she married musician Abbas Shapoori she appeared as ‘Lady Shapoori’, before eventually taking on the pseudonym Pouran.

In the face of her family’s disapproval, she had a glittering career, making 5 films, appearing on television and recording more than 32 hit songs. With a demure public persona – she sang, but did not dance, and her acting roles were chaste – she was at home with both pop and classical Persian music styles. After her marriage to Shapoori fell apart, she remarried and moved to the US before the revolution. Suffering from cancer, she returned to Iran in 1990 to see her grandchildren. She reconciled with Shapoori on her deathbed and is now buried in Tehran.

Shohreh Aghdashloo

1952–

11 She Walks in Beauty (Portrait of Shohreh Aghdashloo), 2022

Still working today, Shohreh Aghdashloo (born Shohreh Vaziri-Tabar) is among the most internationally celebrated Iranian-born actors. Like so many performers of her generation, her family opposed her choice of career, hoping she would become a doctor instead. Marriage aged 19 opened doors, and she shot to fame in the 1970s with major film roles in Iran. In 1979, she escaped the revolution, leaving her wealth and her husband behind to start a new life in the UK where she completed a BA in International Relations. Moving to the US, she struggled to rebuild an acting career in Hollywood as an Iranian émigré. Her breakthrough came in the early 2000s, after she was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in House of Sand and Fog (2003). In her recent work she has chosen roles which challenge stereotypes about Middle Eastern women, and she has spoken out repeatedly about human rights abuses in Iran. Of her early career, she recalls, ‘you could see patriarchy in the Iranian cinema… you’d be lucky to find a strong woman in one out of twenty scripts.’

Shahla Riahi

1927-2019

12 Still, I Rise (Portrait of Shahla Riahi), 2021

Iran’s first female film director, Shahla Riahi (born Ghodratzaman Vafadoost), was also an actor who starred in more than 70 films as well as theatre and television work. At 14 she married Ismail Riahi, a stage director and screenwriter, who took her to plays and the cinema and encouraged her dreams of acting. She began appearing on stage in 1944, aged 17, and by 1951 her first film role in The Golden Dreams launched her career. Despite the conservative roles she chose to play, she was cut out of her family and her brother threatened to kill her and her husband. In 1956, she became the first woman in Iranian history to direct a film with Marjan, based on a script written by two friends. ‘It was the time when the movies were either full of fighting or cabaret dancing. I read it and liked it,’ she later remembered. Set in a small village, it tells the tragic story of a poor girl from a Romany family. Out of ‘respect’ for her male lead, Riahi refused to be publicly listed as the film’s director and so her milestone achievement went unrecognised at the time. After the Islamic revolution, she – like many other actors – was summoned to Evin prison for interrogation. After being forced to renounce her previous career and sign a letter of repentance, she was allowed to continue working. She died in 2019, aged 92.

Irene

1927-2012

13 You Don't Own Me (Portrait of Irene Zazians), 2021

Irene Zazians, often known simply as Irene, was born into an Armenian family which had migrated to Iran after surviving genocide by the Ottoman empire. She married at 16 and moved to Tehran, determined to pursue a career on the stage. In 1949, she acted in her first play – Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan – in the Ferdowski Theatre, and from 1957 she appeared on the silver screen. She quickly became known as a sex symbol, breaking conventions around women’s representation onscreen. ‘When you’re young, you’re courageous and daring,’ she explained much later. For a seaside scene in the 1958 film The Messenger from Heaven, she decided to don a bikini. ‘I wore the very first bikini and it caused an uproar, and I didn’t care about it.’ Although Christian herself, she played a Muslim woman in the notorious 1971 comedy The Interim Husband. Directed by Nosrat Kamini, the film satirised Islamic divorce law. When after the revolution she was summoned to the Evin prison in Tehran, her interrogation focused particularly on her participation in The Interim Husband, and she was prevented from taking further acting work. She left Iran for Germany in the early 1980s, but returned two years later, missing her homeland. Both the films she made in the mid-1980s were banned in Iran. She made a final appearance on camera in 2008’s Shirin by Abbas Kiarostami, an experimental film exploring the female gaze. Irene died of lung cancer in 2012 and is buried in the Armenian cemetery in Southeast Tehran.

Googoosh

1950–

14 The Love Addict (Portraits of Googoosh), 2019

Faegheh Atashin, known as Googoosh, is perhaps the biggest star of 20th-century Iran: a true cultural icon for Iranians everywhere. The daughter of an acrobat and entertainer, she began performing aged only 3, and made her first film at the age of 7, becoming a child star. She continued acting but is best known for her prolific music-making, which took inspiration from Western pop, funk and soul. Over the 1960s and 1970s, she released more than 200 songs. She was also beloved for her fashions, popularising the miniskirt as well as a short haircut that became known as the ‘Googooshy’. At the time of the Islamic revolution she was travelling abroad, but she chose to return to Iran; she was imprisoned for a short time before being released on the condition of singing no more in public. ‘They tried hard to erase me – I mean, erase my name, erase my position, erase my songs, erase my face, erase the memory of me,’ she recalled. ‘But they couldn't’: bootlegged copies of her albums remained immensely popular, spreading her fame to new generations. In 2000, she was allowed to leave the country again for the first time and she relaunched her career with a global tour, playing to huge audiences in Europe, North America and the Middle East. Now in her 70s, she lives in Los Angeles and remains a very active performer, singing primarily in Farsi to audiences all over the world. Her latest album appeared in 2021 and she recently released her first perfume.

Katayoun

1939–

15 Eve (Portrait of Katayoun (Amir Ebrahimi), 2021

Katayoun Amir Ebrahimi, one of the most prolific and successful actors of 1960s Iran, was born in Sanandaj in the Kurdish province. Early acting work in theatre and advertisements led to her being physically beaten by her father, who recognised her face on a poster and threw her out of the house. Her first film, The Spider Web, appeared in 1963 in the year Mohammed Reza Shah launched the White Revolution. A radical program of economic and social modernisation, it transformed Iran and – among other things – gave women the right to vote for the first time. Over the following decade Katayoun made almost 50 films, including director Ali Hatami’s light-hearted Hassan the Bald (1970), the first Iranian musical.

In a recent interview, she lamented the way that the Islamic revolution in 1979 decimated the cinema industry. ‘There has been revolution in Russia, in France, but in none of those countries did they push aside artists, doctors and engineers. What sin did we commit that we could not act in movies, be comfortable and lead our lives?’ She still lives in Iran and in the early 2000s, after a long hiatus, began acting again on television.

Haydeh Changizian

1945–

16 A Dream Deferred (Portrait of Haydeh Changizian), 2022

Haydeh Changizian is the former prima ballerina of the National Ballet of Iran. Born at the end of the Second World War during Iran’s occupation by Allied forces, she trained in Germany and the Soviet Union before returning to Tehran. By 1972, she had become the lead female dancer of the National Ballet, fabled for her dramatic performances of classic roles. In 1978, she left to establish her own company, the Niavaran Cultural Dance Company, seeking to merge classical ballet with elements drawn from Persian history, literature and mythology. In collaboration with the Royal Academy of Dance in London, she also founded the Haydeh Changizian Ballet Institute. Her career was interrupted by the Islamic revolution the following year, which forbade female ballet performances. She left for the US where she continued a distinguished dance career in California and promoted Iranian arts more broadly, including founding and directing the Haydeh Changizian Dance Centre and the Anahita Arts and Dance Cultural Center. She now divides her time between Lisbon and Tehran, where she is working to create a museum of dance.

Soosan

1943-2004

17 The Voice Within (Portrait of Soosan), 2021

Soosan (born Golandam Taherkhani) was a hugely popular Iranian singer during the 1960s and 1970s. Her parents died at a young age, so she lived with an aunt, and there she met a woman called Soosan who sang in the local cabarets. When she died, Taherkhani took her name and she began performing in local clubs at only 13. Her great renown began with performances in Tehran’s leading nightclub Shekufeh No, and by 1969 she was making the first of several appearances on Iran’s cinema screens. Like Mahvash and others, she belonged to a tradition of ‘mardomi’ or street music, beloved by urban working-class audiences, and she also covered songs by performers such as Delkash, Qomar al-Muluk Vazeri and Molouk Zarabi.

Taherkhani was nicknamed ‘Soosan Kouri’ (blind Susan) due to her small eyes, which she accentuated with makeup. Extremely generous, she gave away much of her earnings, paying for girls’ educations and funding a hospital in her hometown. After the revolution, she was imprisoned for illegal singing and escaped Iran through smugglers who stole her money and valuables on the way. She eventually settled in California where she died in poverty in 2004, after complications from shoulder surgery. She is remembered not only through numerous recordings but also in the book of verse named after her by noted Iranian poet Mansour Owji. The titular poem includes the lines ‘This is Soosan who sings / shouting the nights of agitation, in the valleys of snow, and under thousands of hanging daggers’.

Fakhri Khorvash

1930–

19 Desiderium (Portrait of Fakhri Khorvash), 2020

Fakhri Khorvash (born Fakhri Asvadi) is a veteran theatre and film actor. Training initially as a doctor, she then worked as a teacher before moving onto the stage with a production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist drama Dirty Hands (1948). ‘It was an instant hit’, she remembers, and she subsequently received invitations to start acting in cinema. As so often for Iranian women of her generation, her family vehemently objected to her acting and she became estranged from her parents for 9 years. In 1971, her film Mr. Naïve won a prize at the 7th Moscow International Film Festival, and in 1976 she starred alongside Shohreh Aghdashloo in Mohammad Reza Aslani’s cult New Wave film Chess of the Wind, as a paraplegic woman whose family is struggling for control of her fortune. Politically controversial for its critique of the Pahlavi monarchy, the film was banned and believed lost for decades before recently resurfacing to critical acclaim.

Unusually, Khorvash was allowed to continue working after the 1979 revolution and made her most recent film, A Little Kiss, in 2005 at the age of 76. In recent years, she has been outspoken about the oppression of women in contemporary Iran: in a 2016 documentary, she asserts that ‘a wife has no say, she’s always a subordinate… the problem is in our laws, our traditions.’ In 2010, she was honoured for her lifetime achievement at the Iranian Film Festival in San Francisco.

Zari Khoshkam

1947–

20 Tobeh (Portrait of Zari Khoshkam), 2020

Zari Khoshkam is an actor who became a star in the vibrant world of 1970s Iranian film. She was married to the famous director and screenwriter Ali Hatami, with whom she often collaborated. After the revolution, Khoshkam was one of the first actors to be declared chaste and allowed to continue to perform – but only after changing her name to Zahra Hatami and renouncing her previous identity with a letter of repentance. Although she continued intermittently to make films, her career dwindled until a recent resurgence of activity in the last decade. Her daughter is the celebrated actor Leila Hatami.

Azar Shiva

1940–

21 Anarchy of Silence (Portrait of Azar Shiva), 2022

The actor Azar Shiva started dubbing foreign films in the late 1950s, while she was training to be a nurse. Her first film, The Song of the Village (1961) launched a glittering acting career: she took on 21 film roles over the following decade, including Mohammad Ali Fardin’s King of Hearts (1968), a romantic melodrama about a couple separated by fate. In 1970, she won a prize for best female actor at the Sepas Film Festival, but the following year, at the height of her fame, she chose to boycott her own industry. Shiva’s refusal to continue acting was a protest against Filmfarsi’s sexual and financial exploitation of female performers, who often went unpaid or were pressured into erotic scenes irrelevant to the storyline. She publicly declared that rather than take any more demeaning, objectifying roles, she would sell chewing gum – which she did, outside of the University of Tehran. Sadly, her protest went unheard, and she made no further films. Interviewed for a 2016 documentary, she commented that women ‘have always been under the weight of patriarchy. We are like a water drop, trying to bore its way through a rock.’ After the revolution in 1979, she moved to Paris with her daughter.

Monir Vakili

1923-1983

22 Rhapsody of Innocence (Portrait of Monir Vakili), 2022

Iran’s most renowned soprano, Monir Vakili, was born in Tabriz on December 19, 1924. After earning a scholarship to study voice and acting at the Conservatoire Nationale de Musique de Paris, Vakili returned to Iran and was employed as a soloist for the popular National Orchestra. Regular appearances on Sabet TV and at Tehran’s Farhang Hall made her a household name, featured on magazine covers and in editorials throughout the country. She later earned a degree in opera directing from the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

Vakili’s love of opera permeated her entire life and career. She co-founded the first opera company in 1961, appeared in numerous European operas on national tv and stage and was a major force in the completion of the Roudaki Hall, Tehran’s first opera house in 1976. She became Executive Director and Producer of the Hall’s programs for NIRTV, presenting the best of the season’s programs for the masses. She was executive producer of the first Music and Opera Festival at Roudaki Hall. Vakili was most passionate about the Academy of Voice that she founded in 1976, a state-funded boarding school in Tehran for young boys and girls to study opera and choral singing.

Vakili’s greatest gift and legacy to Iran was an award-winning album of 8 folk songs, “Les Chants Et Danses De Perse” in 1958 that became an international success, a first for an Iranian artist.

Monir Vakili was forced to escape her country after the revolution of 1978-79. Her tragic and early death in a car crash in 1983 left the Iranian people in mourning, a loss compounded by the devastating events occurring in her homeland.

Jaleh Sam

1949–

23 Without You (Portrait of Jaleh Sam), 2020

Jaleh Sam was born in Tehran to a middle-class family. After receiving her diploma at age 18, and with the support of her family, she began her acting career with the film Leyli and Majnoon in 1970. Over the next six years, during the economic boom of 1970s Iran, she appeared in nine films including key works of the Iranian New Wave movement such as The Postman (1972) and The Eighth Day of the Week (1976). The Postman was the most successful film of her career, winning major awards at the Cannes and Berlin film festivals. Its central character, the titular postman, represented the struggles of the poor against the Shah’s programme of rapid modernisation. Sam played his alluring but unfaithful wife, whom he murders at the end of the film in an expression of his misogyny and alienation. From 1976, disillusioned by the sexism of the film world, she left Iran for Paris where she pursued a career in fashion modelling and design.

Pouri Banaaei

1940–

24 The Immortal Beloved (Portrait of Pouri Banaaei), 2022

Among Iran’s most distinguished living actors, Pouri Banaaei worked prolifically in film between 1964 and 1979 – the years of the Shah’s White Revolution. Aged 24, despite having no acting experience, she secured a breakout first role in director Nosratollah Vahdat’s film comedy The Foreign Bride. Vahdat was a distant relative and Banaaei impressed him with her determination, chopping off her long hair to prove her commitment to securing the role.

Banaaei starred in many iconic works of Filmfarsi as well as classics of the Iranian New Wave, such as Masoud Qimiai’s iconic noir revenge drama Qeysar (1969), which she personally financed with a bank loan but was never reimbursed or paid for her work. In fact, she recalls that as a female actor she was frequently unpaid. After the 1979 revolution, like other Iranian actors, she was summoned to the Evin prison for interrogation and asked to sign a letter of repentance; she courageously refused, saying she had done nothing to be ashamed of. Apart from Shirin in 2008, she now chooses not to continue acting work, saying ‘My passion is to be in charitable affairs and help my compatriots’.

Forouzan

1937-2016

25 Hey Baby I'm a Star (Portrait of Forouzan), 2019

Filmfarsi superstar Forouzan was born Parvin Kheirbakhsh in the north of Iran. Starting her career dubbing foreign films, she had her first acting role in 1963. Her breakthrough came with the release of Ganje Qarun (Qarun’s Treasure, 1965): a huge commercial and popular success, it made her reputation as one of Iran’s most alluring and bankable actors. With her magnetic appeal, Forouzan was often cast as a cabaret singer or sex worker who serves as a love interest for the male lead. Although she was the best paid female perfomer in the industry, making more than 60 films in total, the degrading working conditions took a toll on her spirits. In a 1972 interview she said, ‘I am sick, sore, and exhausted. I am tired of standing in front of the camera listening to the director telling me “be a little sexier, a little more lustful, bring your skirt higher, be a little more inciting and provocative.”’

After the Islamic revolution in 1979, she remained in Iran. She was released from prison after signing a letter of repentance, but her money and property were seized by the courts. She never again gave interviews and died in obscurity in 2016.

Jamileh

1946–

26 The Dancing Queen (Portrait Jamileh), 2019

Jamileh (born Fatemeh Sadeghi) was raised by her father who worked in theatre, and by the age of six, she was joining him onstage. She was first married aged 14 and had her first daughter not long afterwards; by her late twenties she was widowed by her second husband, with two children to care for. Like other Iranian entertainers of the time, Jamileh’s talent for dance provided her the opportunity to perform onscreen. She played dance-related roles in more than 25 films and was reportedly the highest-paid cabaret actor of Iranian origin in 1974.

Jamileh’s performances and film roles popularised various folk dances in Iran: she was especially renowned for belly dance and Bandari as well as classical Persian dance. She was also the first woman to dance in the subversive, genderbending jâheli style, which involves channelling the swagger of a jâhel (a hypermasculine, tough-guy type), typically in a dark fedora hat. In 1977 Jamileh left for the US, and after the revolution was unable to return. She continued dancing in Los Angeles well into her fifties. She remains in exile.

Delkash

1925-2004

27 Memories of You (Portrait of Delkash), 2019

Before she became one of Iran’s most famous singers, Delkash (born Esmat Bagherpour Baboli) grew up in a family of ten children in Babol, known as the ‘city of orange blossoms’. She grew up listening to her mother recite verses from the Koran, and to the distinctive folk songs of her region. She was twelve when her father died and her mother sent her to live with her older sister in Tehran, where the extraordinary range and depth of her alto voice was discovered by music teachers. One of them chose for her the stage name ‘Delkash’, which translates as ‘delightful’. In 1945, she launched her singing career with an appearance on the state-sponsored Radio Tehran; she and her ensemble would go on to perform live on air every Sunday evening until 1952. With her preeminent reputation for reinterpreting Persian classical and folk music, she recorded a remarkable 370 songs over the next three decades, as well as writing music under the pen name Niloofar.

Delkash’s beauty and popularity led to a string of major film roles from the early 1950s, many of which were directed by Esmail Koushan. Controversially, in Top Dog (1958), she was the first woman to cross-dress on screen, appearing in drag as ‘Jahel’, an archetypal tough guy whose ballad became a radio hit. From the 1960s, she returned to focusing on her music until female soloists were banned from performing after the revolution. In her seventies in 1998, after a long absence from the stage, she gave a series of concerts for rapt expatriate audiences in London, New York and Canada. She died in Tehran in 2004. After her death, word spread of her extensive charity work.

Faranak Mirghahari

1942–

28 Bang (Portrait of Faranak Mirghahari), 2019

Born in the north of Iran, Faranak Mirghahari is famous for her work in 1960s Iranian cinema. As a young girl her father encouraged her participation in the arts, and at 17 she was spotted by the leading film noir director Samuel Khachikian who invited her to star in The Hill of Love (1959). Her father agreed to her participation, with the stipulation that filming would take place during the summer holidays and would not include sexualised scenes. Over the next few years she became one of the country’s most popular actors, making a remarkable seven films in 1961 alone. One of these was 1962’s The Last Hurdle, directed by Khosrow Parvizi: in contrast to the passive or manipulative roles so common for women in Filmfarsi, Mirghahari played a character who shoots her way through the patriarchy. Between 1963 and 1965 her film appearances were fewer as she started refusing roles that she found poorly written, but she otherwise remained prolific throughout the 1960s. In the early 1970s, she had a short-lived marriage to Dariush Moeeni, who prohibited her from further acting. After 1979, she left Iran for the US, where she helped to organise the first concert for exiled Iranian performers in Los Angeles. Living in the US in 1992, she reconnected with her childhood love, and they married soon after.

Fereshteh Jenabi

1948-1998

29 The Woman in the Mirror (Portrait of Fereshteh Jenabi), 2021

Iranian actor Fereshteh Jenabi was born in 1948 as Fereshteh Jenabi Namin. Few details of her life are known, but she was very successful in the 1970s, performing in 11 films between 1971 and 1978. In two of these films – Resurrection of Love (1973) and Speeding Naked Til High Noon (1976) – her character orgasms on camera, an audacious expression of female pleasure in a deeply conservative society. Following the 1979 Islamic revolution, she received a death sentence for this work. Afraid for her life, she went into hiding for nearly 20 years and became dependent on drugs. Whether it was suicide or overdose, she died aged only 50 in Tehran.

Kobra Saeedi

1946–

30 Kobra (Portrait of Kobra Saeedi), 2022

Kobra Saeedi, better known by her stage and pen name Shahrzad, was a renowned dancer, actor, filmmaker, journalist, and poet before the 1979 revolution. Growing up poor, with an abusive father, she never completed her formal education and started dancing in nightclubs as a teenager to support her younger siblings. In the late 1960s, she started appearing frequently in films – often, to her dismay, as a cabaret dancer whose seductive performances had little if any connection to the plot. In the 1970s, at the height of her fame, she moved away from these unsatisfactory roles into writing and directing. ‘I stopped dancing so that men could stop watching my body and so that they could listen to what I had to say,’ she later explained. Despite the sexist responses she encountered as a former dancer, she published three books of poetry and one of prose. She also wrote and directed the film Maryam and Mani, starring the famous film star Pouri Banaaei.

Following the Islamic revolution, Shahrzad attended a protest against mandatory female veiling on the occasion of International Women’s Day, bringing an 8 mm movie camera with her to document the event. She was arrested and sent to Evin Prison, followed by several years in psychiatric institutions. By the time she was released, all her belongings had been stolen and she was left destitute. In the mid-1980s she came to Germany as a refugee; unable to support herself, she returned to Iran where she was homeless for decades. In 2015, she was the subject of a documentary, Shahrzad’s Tale, after which she was given basic housing by her fans in Kerman, in south-central Iran.

Nosrat Partovi

1944–

31 Baptism of Fire (Portrait of Nosrat Partovi), 2022

Like so many female performers of her time, the life of actor Nosrat Partovi is poorly documented. Born in Tehran in 1944, she only ever made one film – The Deer (1974). Directed by Masoud Kimiai, the film tells a story about those pushed to the margins of Iranian society. Partovi portrays a character called Fati, a cabaret dancer who lives with a drug addict played by Behrooz Vossoughi, who was among the most famous Iranian actors of the 1970s. The Deer gives a glimpse of the fractured lower-class communities left in the wake of the sweeping modernisations initiated by Mohammed Reza Shah in the 1960s, which saw many unskilled rural workers pushed into urban destitution. In August 1978, the film took on a tragic new significance: during a screening in Abadan, the Cinema Rex was locked and set on fire, resulting in hundreds of people burning to death. This terrorist attack is usually attributed to radical Islamists who saw cinema as a symbol of Western immorality and corruption; others blamed the Shah’s secret police. The social unrest that followed the attack helped ignite the revolution, ending the Pahlavi dynasty and ushering in a new Islamic Republic within months. Partovi’s current whereabouts are unknown.

Further Resources

If you would like to learn more about these histories, then we have suggested some resources below.

Filmfarsi (2019), dir. Ehsan Khoshbakht

Razor's Edge: The Legacy of Iranian Actresses (2016), dir. Bahman Maghsoudlou

Houchang Chehabi, ‘Voices Unveiled: Women Singers in Iran’, in Rudi Matthee and Beth Baron, eds., Iran and Beyond: Essays in Middle Eastern History in Honor of Nikki R. Keddie (Costa Mesa, Cal.: Mazda, 2000), pp. 151-166

Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, volume 1 (The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941) and volume 2 (The Industrialising Years: 1941-1978), (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011)

Kamran Talattof, Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of Popular Iranian Female Artists, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011)

Because these women and their creative lives were not always valued, their stories have been difficult to trace. We have worked with Soheila, the women who are still alive, and surviving family members, to gather the information offered here. However, these narratives are very much a work in progress.

We warmly welcome any further information you might be able to share: please contact [email protected]

Eleanor Nairne, Curator;

Hilary Floe, Assistant Curator;

Tobi Alexandra Falade, Curatorial Trainee.

Historical timeline

1907

Although ruled by the Qajar kings since 1797, Iran has long been subject to political interference by foreign powers. In 1907, a treaty between Britain and Russia carves up the country into two spheres of influence.

1908

A British businessman discovers crude oil, leading to the formation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), later BP. In 1914, the British government becomes the majority shareholder, gaining direct control of – and the bulk of the profits from – the nation’s oil industry.

1921

Backed by the British government, army commander Reza Khan stages a military coup in February. The young king, Ahmad Shah, is side-lined and Reza Khan appoints an ally as prime minister.

1923-5

Reza Khan consolidates power rapidly: he is appointed prime minister in 1923 and then has himself installed as Shah in 1925, ushering in the Pahlavi dynasty. He starts to radically modernise and secularise the country’s society, economy and infrastructure, but social inequality remains rampant.

1936

Reza Shah introduces a decree which bans the traditional practice of women’s veiling, and he encourages western-style dress. The ban on veils is aggressively enforced by police and attracts great controversy.

1941

Although Iran declares neutrality in the Second World War, the country is perceived as a potential threat by the Allies. In August, British and Soviet forces invade Iran, forcing the Shah’s abdication in favour of his son Mohammed Reza Pahlavi.

1942-6

In January 1942, Britain and the Soviet Union agree to withdraw their troops within 6 months of the war’s end. Under occupation, however, Iran is devastated by economic chaos, famine, and epidemic typhus.

1949

Mohammed Reza Shah expands his powers after a failed assassination. Politician Mohammed Mossadeq rises to prominence in opposition to his rule, seeking to promote democracy and reduce foreign influence within Iran.

1951

After Mossadeq’s centre-left coalition is elected to a majority in parliament, the Shah is compelled to appoint Mossadeq as prime minister. With widespread popular support, Mossadeq nationalises the Iranian oil industry, leading to a confrontation with the British, who had long profited from Iran’s natural resources. Britain enforces an oil embargo, which devastates Iran’s economy.

1953

Backed by MI6, the CIA orchestrates a coup that topples Mossadeq’s government and restores the pro-western Shah to power.

1957

Mohammed Reza Shah forms the SAVAK intelligence service and secret police, which suppresses political opponents and censors some cultural production.

1963

The Shah launches the ‘White Revolution’, a sweeping plan of economic modernisation and compulsory education, underpinned by ambitious land reform. Nationwide protests follow, led by emerging religious figures such as Ayatollah Khomeini. For the first time, women are allowed to vote and run for elected office, but working-class deprivation and illiteracy remain prevalent.

1971

Leftist militants attack a paramilitary police station in northern Iran, setting the stage for an ongoing urban guerrilla struggle against the Shah’s regime.

1973

An oil crisis leads to sharp increases in the price of oil. The influx of ‘petrodollars’ spectacularly benefits the Iranian economy, but the new wealth is unevenly distributed.

1977

Growing anger about the Shah’s authoritarian leadership leads to open letters and demonstrations from both left-wing and right-wing communities.

1978

In August, Islamist terrorists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan during the screening of the film The Deer, and hundreds of people die. The event is one of the key flashpoints leading to the 1979 revolution, and political unrest spirals into mass protest. In September, police fire on anti-Shah protesters in Tehran in what becomes known as the ‘Black Friday’ massacre.

1979

Mohammed Reza Shah flees in January, ending Pahlavi rule, and Ayatollah Khomeini takes power. Khomeini’s fundamentalist Islamic agenda reshapes Iranian society: by 1982, women are forced to wear veils again and are prohibited from most roles in public life, restrictions that continue to this day.

Film & Music

Find out more about the sounds of Rebel Rebel

Soheila Sokhanvari: Rebel Rebel Soundscape sources:

00:00 Googoosh (singer) – extract from the song Talagh

02:41 Fakhri Khorvash (actor) – extract from the film Bi-Gharar (1973)

03:13 Ramesh (singer) – extract from the song Rood Khooneha

05:55 Molouk Zarabi (singer) – extract from the song Nazanin Gole Maryam

07:07 Mahvash (singer) – extract from the song Did Bezan

08:09 Delkash (actor/singer) – extract from the film Tomorrow is Bright (1960)

10:03 Soosan (singer) – extract from the song Dooset Daram

10:51 Forough Farrokhzad (poet/film director) – extract from the film The House is Black (1962)

11:31 Googoosh (singer) – extract from the song Khabam Ya Bidaram

13:40 Monir Vakili (opera singer) – extract from the song La Laiee

16:31 Pouran Shapoori (actor/singer) – extract from the song Molla Mammad Jaan

19:00 Forough Farrokhzad – extract from her poem Born Again with her own narration

19:44 Googoosh (singer) – extract from the song Hejrat

21:59 Forouzan (actor) – extract from the film Dayereh Mina (1978)

22:49 Ramesh (singer) – extract from the song Labe Darya

Please note that some of the audio extracts have been lightly remastered with noise-reduction for clarity purposes.

The Star (2022): Film Clips

This work includes excerpts from the following films made before the Iranian revolution in 1979, and from two later documentaries.

Forouzan in Raghaseye shahr (1970), dir. Shapoor Gharib

Katayoun Amir Ebrahimi in Dozdeh siyahpoush (1968), dir. Amir Shervan

Katayoun Amir Ebrahimi in Razor’s Edge (2016) dir. Bahman Maghsoudlou

Katayoun Amir Ebrahimi in Hassan kachal (1970), dir. Ali Hatami

Fakhri Khorvash in Bigharar (1973), dir. Iraj Ghaderi

Forouzan in Dayereh mina (1978), dir. Dariush Mehrjui

Forouzan in Dokhtare shahe parion (1968), dir. Shapoor Gharib

Ramesh in Rangarang (date and director unknown)

Soosan in Rangarang (date and director unknown)

Googoosh singing Gharibeh ashena (date and director unknown)

Googoosh singing Makhloogh in Rangarang (date and director unknown)

Shohreh Aghdashloo in Sooteh delan (1977), dir. Ali Hatami

Katayoun Amir Ebrahimi in Shahrahe zendegi (1968) dir. Iraj Ghaderi

Forouzan in Raghaseyeh shahr (1970) dir. Shapoor Gharib

Fereshteh Jenabi in Ghiyamateh eshgh (1973) dir. Houshang Hessami

Haydeh Changizian in Tehran, Balle Nadarad (2012) dir. Ali Hamedani

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Tannaz and Oranus Abbasioun, Jordan Amirkhani, Haydeh Changizian, Firoozeh Khatibi, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Bahman Maghsoudlou, Sara Makari, Siavush Randjbar-Daemi, ZaZa Saleh, Katy Shahandeh, Jonathan Sokhanvari, Soheila Sokhanvari, and Kamran Talattof for their help in the preparations of this guide.

The exhibition has been commissioned by the Barbican, and is generously supported by the Bagri Foundation, Arts Council England, and the Soheila Sokhanvari Exhibition Circle: Marie Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre (Spirit Now London), Sayeh Ghanbari, Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, Elizabeth and J. Jeffry Louis, Pat and Pierre Maugüé, Hugh Monk, and those who wish to remain anonymous. Paint courtesy of Little Greene.

You can champion work in the Curve. Donations help us to present emerging and international artists, keeping it a free space for all to discover and enjoy. Support today by visiting barbican.org.uk/donate. Thank you.

The Barbican Centre Trust Ltd, registered charity no. 294282

Barbican Centre, Silk Street, London EC2Y 8DS