From Art Brut to Outsider Art:

A Little History of Art Beyond the (So-Called) Mainstream

Curatorial Assistant Charlotte Flint explores the origins of Jean Dubuffet’s phrase ‘Art Brut’, its impact on art history, some of the different artists whose work he collected, alongside the importance of ‘Art Brut’ in a contemporary context.

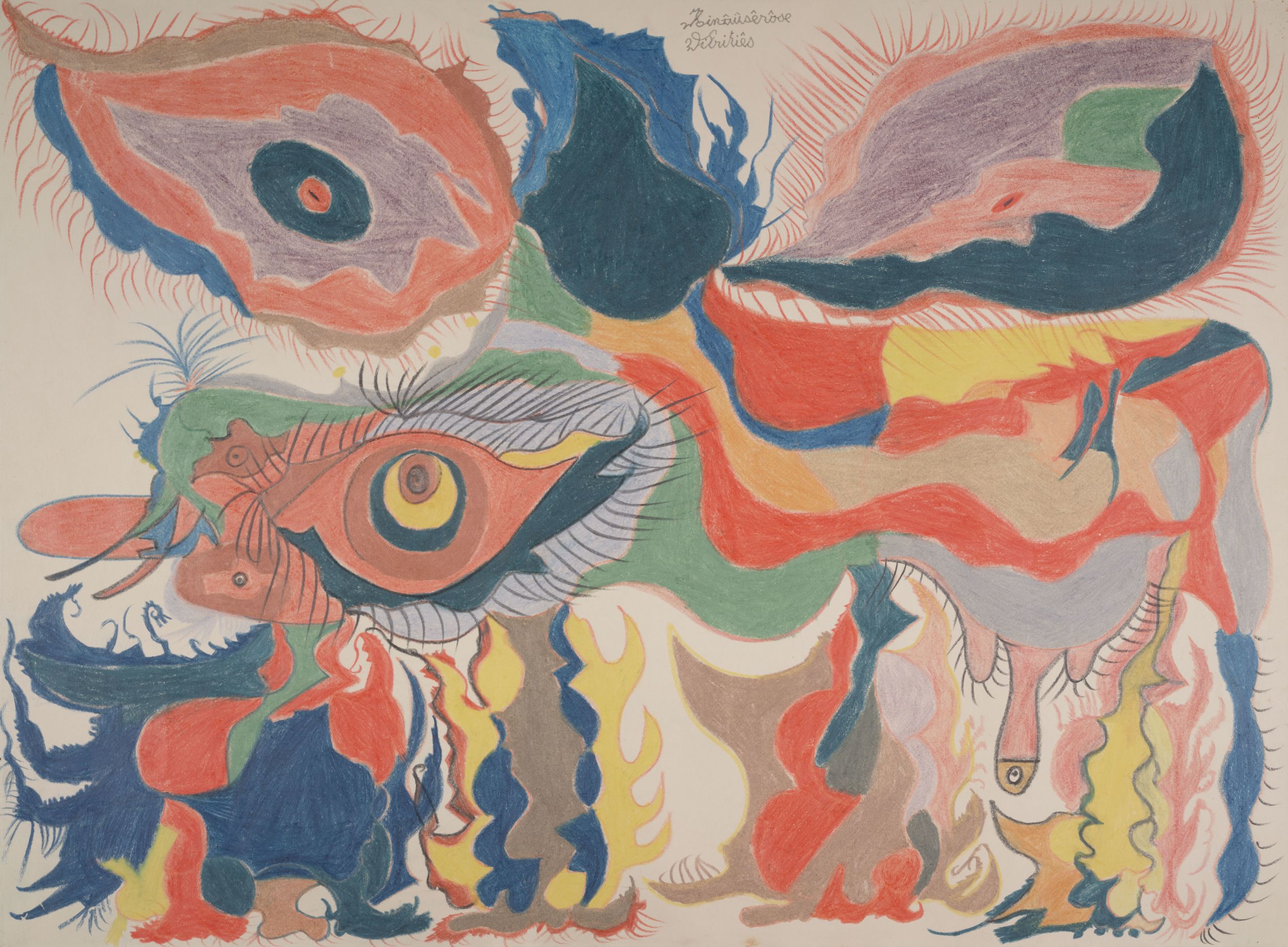

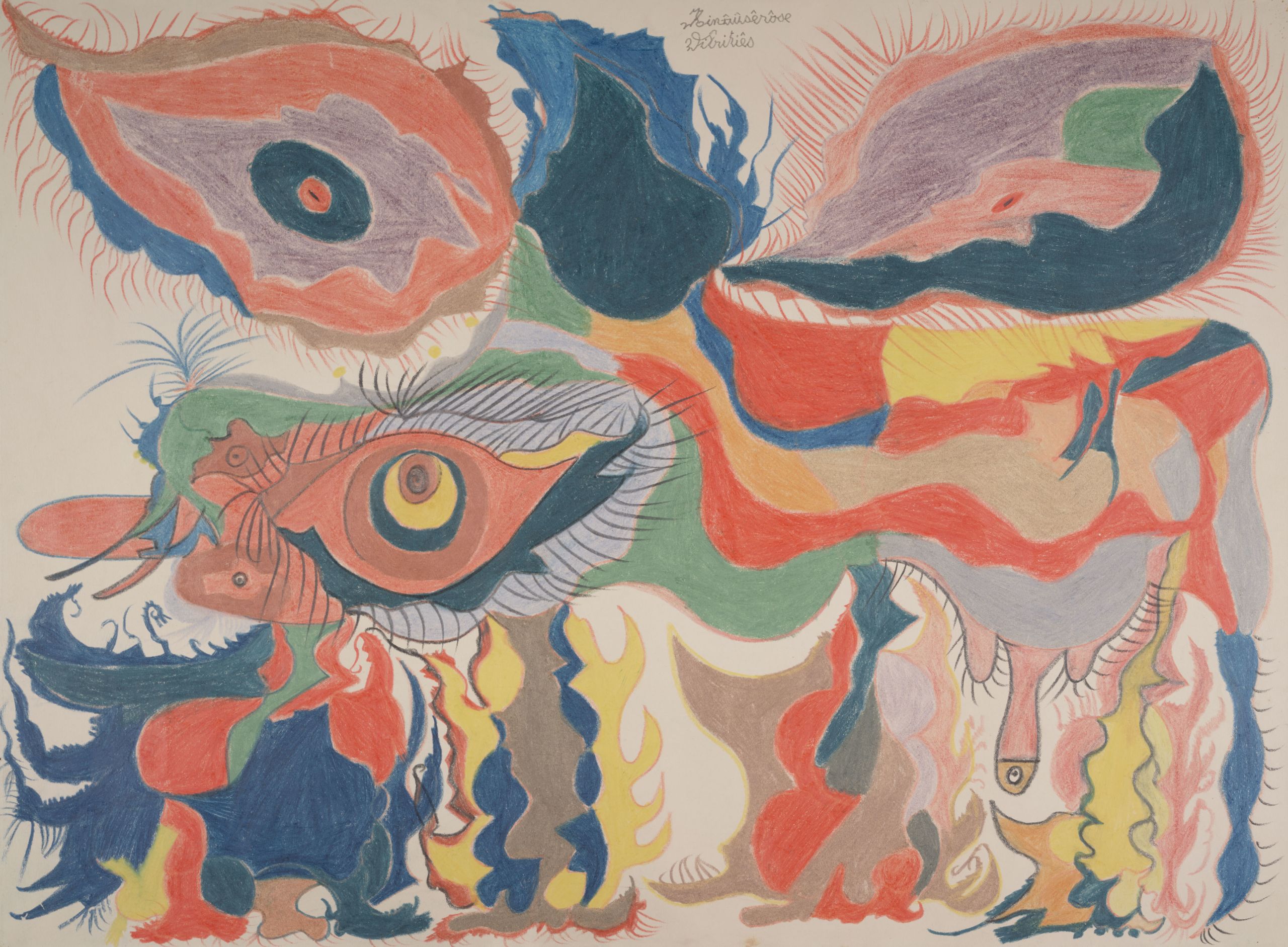

‘Art Brut’ is a term that was coined in 1945 by the French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-85) to refer to art made by individuals working outside of the established cultural mainstream. In English, it tends to be translated as ‘Outsider Art’, which is the phrase Roger Cardinal used for his book on the topic in 1972. But since Dubuffet fought against established cultural norms and was critical of labelling anyone an ‘outsider’, we’ve decided to keep his original term throughout our discussions of this work.

By the end of his life, Dubuffet had collected more than 5,000 artworks by these artists who were a powerful source of inspiration for him. Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty features the work of sixteen Art Brut artists alongside his own work, demonstrating the important role they played in shaping his thinking on what art could be. Dubuffet was the first to admit that Art Brut was a slippery term to define and the concept shifted over the course of his lifetime. In this essay, we explore the history of the term within art history and through the lens of Dubuffet’s work.

‘Naturally, Art Brut is very difficult to define without getting confused… But there is no reason for saying that something does not exist because it is elusive and indefinable’

Dubuffet quoted in Lucienne Peiry, Art Brut: The Origins of Outsider Art

After briefly studying at the Académie Julian in Paris aged 18, Dubuffet grew frustrated with the academic traditions of the ‘Beaux Arts’. He abandoned his training and decided to pursue what he considered to be a more ‘authentic’ artistic language. Drawn to the work of self-taught artists, which he felt was ‘more alive and passionate than any of the boring art that has been officially catalogued’, he became interested in art made by graffitists, tattooists, spiritualists, incarcerated people, and individuals in psychiatric care. Between 1945 and 1971, he collected more than 5,000 artworks by 133 creators; he called this work ‘Art Brut’, which literally means ‘raw’ or ‘crude’ art.

Early inspirations

While doing his military service in 1923, Dubuffet came across the sketchbooks of the psychic Clémentine Ripoche who drew imaginary scenes unfolding amid clouds which captured his interest and prompted further exploration of the work of untrained artists – these drawings were Dubuffet’s first encounter with what he would later term Art Brut.

Dubuffet’s relationship with Art Brut was like an enduring but volatile love affair. He built a thriving network of artists, curators, historians, writers, and doctors who assisted him in his mission to uncover the work of remarkable, largely unknown, artists. But over the years he became mired in complexities of his own making. In a 1977 interview with the art historian Michael Peppiatt, Dubuffet said:

‘I’ve always thought that the most powerful and vital art – like Art Brut – is the one society has the most trouble in accepting. Well, my success has put me in an uncomfortable position’.

To understand better the contradictions of Dubuffet’s concept of Art Brut, it’s useful to address a longer history of art from beyond the cultural mainstream.

First use...

The term ‘Art Brut’ was first used in a letter written by Dubuffet to his friend René Auberjonois on 28 August 1945 following a visit to Switzerland to see the work of artists marginalised from mainstream culture, including patients in psychiatric care.

‘We mean by that term works done by people uncontaminated by artistic culture, works in which the sense of mimicry, contrary to what happens among intellectuals, plays little or no part, with the result that their makers draw all… from their own being and not from hangovers of classical or fashionable art’.

‘Millions of expressive directions were available outside the avenues of patented culture…’

Dubuffet in Peiry, 'Art Brut'

In 1922, the German psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn published Artistry of the Mentally Ill – a ground-breaking book that explored the relationship between mental health and creativity. Prinzhorn began working at the Heidelberg Psychiatric Clinic in 1919 and started collecting work made by patients in a clinical context, amassing more than 5000 drawings, paintings, and carvings from hospitals across Germany and Switzerland. Prinzhorn was captivated by these artworks, and this intense period of research and collecting formed the basis of Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Prinzhorn described his collection as ‘consist(ing) mainly of spontaneously created pictures by untrained mental patients’. Some medical colleagues were dubious, but the book, with its rich illustrations of 180 works, was enthusiastically received by artistic avant-garde circles at the time.

In Paris, Prinzhorn’s book was pored over by artists who found in its pages a more honest form of expression than the fashionable French art of the time. The German artist Max Ernst had a pre-existing interest in the art of psychiatric patients; after reading the book, he lent his copy to his friend, the poet Paul Éluard. Subsequently, it was passed to the artistic couple Jean and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the writer and co-founder of Surrealism André Breton and, in 1924, to Dubuffet, who was astonished by it. Although he could not read the German text, he later recalled in an interview in 1975, that the ‘illustrations made a profound impression on me… they offered me a new direction that was truly liberating for me. I realised that anything was allowed, everything was possible’.

The discovery of Prinzhorn’s text and the art of patients was transformative for Dubuffet – so much so that he doubted his own capacity for creativity after the encounter and didn’t produce a single work for nearly a decade.

An energy for collecting

Throughout his life, Dubuffet poured a phenomenal amount of time, energy, and money into collecting and researching Art Brut, and took advantage of his own acclaim to foreground the work of these lesser-known artists. It was a labour of love that was fuelled by his unwavering belief in the importance of these artworks.

One donor to Dubuffet’s collection recalled: ‘It was astonishing to see how much satisfaction (the artworks) gave him… he became feverish. It was truly the greatest pleasure one could have granted him: to bring in new things, new creations’.

Installation view of Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty. Barbican Art Gallery, 17 May – 22 August 2021. Photo: Marcus Leith

Installation view of Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty. Barbican Art Gallery, 17 May – 22 August 2021. Photo: Marcus Leith

The Art Brut Journey

In 1945, Dubuffet travelled to Switzerland with his friend Jean Paulhan and the architect Le Corbusier to learn more about artists marginalised from mainstream culture, including patients in psychiatric care. Dubuffet undertook more than twenty interviews while in Switzerland with publishers, doctors, curators and writers, and this trip formalised the idea of ‘Art Brut’.

‘I preferred ‘Art Brut’ instead of ‘Art Obscur’ [Obscure Art], because professional art does not seem to me any more visionary or lucid; rather the contrary. It would add to the confusion… Why then do you write that gold in its raw state is more fake than imitation gold? I like it better as a nugget than as a watchcase’.

Dubuffet returned to Paris with two suitcases full of artwork and a mind overflowing with ideas: his aim was to write and illustrate sixteen short journals to draw attention to these artists. He embarked on a period of energetic research and collecting, forming a notable network of contacts across Europe who would assist his search. Dubuffet simultaneously worked to define his criteria; while he had collected many examples of art made in psychiatric hospitals, Art Brut was by no means a shorthand for art made by those with mental illness. For example, some of his early acquisitions were works by the self-trained cork-carver Joaquim Vicens Gironella (1911-1997), the Spiritualist painter Fleury-Joseph Crépin (1875-1948) and an innkeeper called Henri Salingardes (1872-1947) who poured cement medallions in his garden before decorating them with paint, glass and fur.

Dubuffet proclaimed that ‘Art Brut is hidden, and help is needed to locate it’ and set about this task with verve. He formed a committee of like-minded individuals to assist him in his mission, he opened a devoted exhibition space and organised radical displays – French critic Michel Ragon recalled ‘the shocking effect that (the) exhibitions had on me… There was indeed something new there and far more exciting than most art by “artists”’ – and wrote texts about Art Brut and its creators. This frenzied period of activity lasted for several years but it had begun to test Dubuffet’s patience – he felt Art Brut was distracting him from his own work.

In 1951, Dubuffet decided to send his entire collection to the home of artist Alfonso Ossorio in East Hampton, New York, where he had offered to take care of it. In December, 1,200 artworks by 120 artists and the accompanying filing cabinets filled with documentation were shipped from Paris to America, where they remained for almost ten years. Ossorio displayed the artworks prominently within his home where it attracted attention from artists including Marcel Duchamp, Barnett Newman, and Claes Oldenburg, as well as the director of The Museum of Modern Art, Alfred Barr. Dubuffet’s decision to relocate the collection to the United States gave him the opportunity to focus on his own practice, and the following years were prolific. However, despite the physical distance between him and the artworks, they were never far from his mind.

A phantom organisation

In January 1952, Dubuffet disbanded the Compagnie de l’Art Brut (a committee of like-minded individuals he had brought together to further his Art Brut endeavours) due to his anger that:

‘Nobody helps me with the work and research… the members do absolutely nothing… they are phantom members and it’s a phantom organisation’

‘Art Brut has been dormant during this vacation… but I am on the lookout’

Jean Dubuffet, letter to Dr R. Gentis, Le Touquet, 23 August 1963, Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut

In 1961, after an impassioned correspondence with Ossorio, the collection was returned to Dubuffet in Paris. He’d renovated a mansion on the rue de Sèvres into six exhibition galleries, accompanied by archives, study spaces and offices, which became the collection’s new home. Dubuffet installed some of his earliest acquisitions alongside new finds by artists including Laure Pigeon, Madge Gill and Émile Ratier, and the dynamic displays were praised by visitors, including the writer Pierre Bettencourt, who described it as ‘a delicious little museum with… so many marvels’. Unlike the earlier exhibition spaces, the site at the rue de Sèvres could only be visited by appointment and Dubuffet referred to it as a ‘laboratory for study and research’, ensuring it was ‘padlocked and reserved for true friends’. This shift from the public facing nature of the early exhibitions to a research facility demonstrates the change in Dubuffet’s attitude towards Art Brut – he moved from being more of a champion and spokesman, to a curator who was mindful about the legacy and historical significance of his collection.

An artist fee

We know that in some instances Dubuffet directly corresponded with artists and arranged to purchase a work for an agreed price. Sales for artworks bought from Miguel Hernandez (1893-1957), Pascal-Désir Maisonneuve (1863-1934), and Henri Salingardes (1872-1947) were documented in ledgers kept at the time. More frequently, artworks were gifted to him, or psychiatrists in psychiatric institutions gave him work they thought would be of interest, and that would be well cared for in his collection. In these instances, patients did not receive a fee and were not aware that their work was being shown in public. Dubuffet was known to send the artists gifts such as paint, brushes, cigarettes, and small amounts of money. Displaying the work of psychiatric patients without their knowledge raises important ethical questions about consent and medical confidentiality and we acknowledge that this is a problematic element of Dubuffet’s collecting practice. Art Brut historians similarly recognise the challenging nature of these donations but have reached a consensus that doctors at this time were acting in good faith and that many had prolonged periods of engagement with their patients and enormous admiration for their artwork.

Exhibition including works from Charles Ladame’s collection in the Foyer de l’Art Brut, in the basement of the René Drouin gallery, Paris, February 1948 . Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Exhibition including works from Charles Ladame’s collection in the Foyer de l’Art Brut, in the basement of the René Drouin gallery, Paris, February 1948 . Courtesy Archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Dubuffet’s spirited energy for Art Brut was rekindled; he exclaimed that these works were ‘representative of cerebral creation in its raw, pure state surging up in all their spontaneity’, and reactivated his network of contacts to begin researching and collecting again. By 1963 he had acquired almost 900 new works and four years later, a presentation of Dubuffet’s Art Brut works was held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. The exhibition, which ran from 7 April – 5 June 1967, included works by more than 60 artists and was visited by over 20,000 people. Presenting these artworks in a renowned institution directly contradicted Dubuffet’s anti-cultural position (he had previously referred to museums as ‘funeral homes’) and the irony was not lost on him.

‘In all honesty, at the start I wanted to introduce into the cultural milieu the idea that cultural art is ridiculous, and that a-cultural art is alone inventive, the only one that ignores the cultural milieu… I caught myself in my own trap, for I find myself today the exhibitor of Art Brut in a cultural milieu, a victim of my own original position’.

The legacy of his collection of Art Brut was at the forefront of Dubuffet’s mind and in September 1971, after several unsuccessful discussions with French institutions, he announced the donation of his entire collection to the city of Lausanne, in Switzerland.

'Outsider Art'

In 1972, art historian Roger Cardinal (who had done extensive research into Art Brut at the rue de Sèvres with Dubuffet) published a book titled Outsider Art (1972), which intended to bring the concept to an English-speaking audience. Cardinal had hoped to use the French term for the text’s title, reasoning that ‘you’ve got art nouveau and art deco, and now you’ve got art brut’ but his publishers did not agree. They eventually decided on ‘Outsider Art’, a term which Cardinal himself struggled with. It sounded as if it were pitching untrained artists against culturally ‘insider art’ and the term has been critiqued as exclusionary, falling out of usage in some contemporary critical debates.

Dubuffet’s collection travelled to Switzerland and was installed in the Château de Beaulieu in Lausanne in 1976, opening to the public on 26 February. At the time, the collection included 5,000 works by more than 133 artists, but the museum has continued to make acquisitions and they now have more than 70,000 works by 1,000 different artists. Relocating the collection to Switzerland was a poignant ode to where Dubuffet’s journey had begun: he described the city of Lausanne as ‘the point of departure for my research and the nucleus of voluntary collaborations that snowballed’. The publication of Outsider Art and the opening of the Collection de l’Art Brut brought further public attention to the work of non-mainstream artists. In May 1977, art collector Victor Musgrave approached the UK Arts Council to present an exhibition of ‘what Dubuffet calls Art Brut’.

Outsiders: An Art without Precedent or Tradition, curated by Musgrave and Cardinal opened at the Hayward Gallery, London, on 8 February 1979. The press release for the exhibition stated that: ‘Outsider art is not a movement but in each case, a highly personal creation of individuals of prodigious talent whose work and even existence is usually unknown to each other, and for the most part little known even to the “official” art world’. ‘Outsiders’ received more than 38,000 visitors but attracted mixed reviews. Musgrave’s partner and collaborator Monica Kinley recalled that ‘the critics couldn't stand it… they condemned it as being the work of mad people. Whether termed ‘Art Brut’ or ‘Outsider Art’, work by these marginalised artists started being assimilated into recognised culture, directly contradicting many of Dubuffet’s original intentions.

Now, ‘Outsider Art’ is seen as a recognisable category, with numerous museums around the world devoted to it and an annual Art Fair dedicated to ‘Self-Taught Art, Art Brut and Outsider Art’.

Who were the Art Brut artists?

The amount of information available varies from artist to artist, in some instances there is a wealth of detail and for others, there is barely anything. For artworks produced by some psychiatric patients, often very little of their biography is known. However, in the cases of Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930) and Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964), two artists who were living in psychiatric hospitals, there are much fuller historical records due to their doctors having encouraged and documented their artistic practice. Dubuffet was a prolific letter writer and his correspondence with artists has been carefully archived. For example, Dubuffet and the artist Gaston Chaissac corresponded for twenty years, sending over 440 letters to each other, and as a result, we have a much fuller account of Chaissac’s life and artistic output.

Why is Art Brut important now?

Dubuffet’s celebration of Art Brut chimes with a contemporary drive to foreground the work of artists who have been marginalised or underrepresented due to their class, race, gender, sexuality, health, or socio-political position. Important work is being done to problematise the established canon of art and to ensure that certain groups of artists are no longer ghettoized or excluded from the heralded narratives of art.

As a white, able bodied and upper-middle class man, Dubuffet acknowledged his position of privilege and never considered himself an Art Brut artist.

‘I don’t merit it. I’m not worthy. My cultural background is too extensive. I never managed to rid myself completely of the influence of cultural art’.

There is no denying that the history of Art Brut is incredibly complex, and Dubuffet’s role in it raises challenging questions: what gave Dubuffet the right to appoint himself the spokesman of this work? And does Art Brut fetishize otherness? This debate is consistently evolving as we engage with these vital questions, and our shifting definitions of art.

Although the histories of Art Brut, and subsequently ‘Outsider Art’, can be problematic, the artworks remain a revelation and we cannot deny Dubuffet’s role in their recognition and legacy. Jean Paul-Ledeur, a conservator who worked for Dubuffet, recalled:

‘When someone would touch his Art Brut objects, he was like a mother with her jars of jam. It was unbelievable! He watched over everything! … He would watch over them as if they were the blessed sacrament. I can assure you, he’s worse than a curator when someone touches the frame of the Mona Lisa’.

In Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty, we’re delighted to be exhibiting work by sixteen remarkable Art Brut artists, alongside Dubuffet’s own work, foregrounding the radical effect they had on his own practice and his understanding of what art had the potential to do.

Featured Artists in 'Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty'

Miguel Hernandez, Aloïse, Maurice Baskine, Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Joaquim Vicens Gironella, Henri Salingardes, Gaston Chaissac, Jan Krížek, Gaston Duf., Augustin Lesage, Laure Pigeon, Madge Gill, Adolf Wölfli, Auguste Forestier, Sylvain Lecocq, Scottie Wilson.

You can read their artist biographies in the Exhibition Guide.

Further Reading

If you're interested in learning more about Dubuffet and Art Brut, we recommend:

- Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art, 1972

- Carine Fol, From Art Brut to Art without Boundaries: A Century of Fascination through the Eyes of Hans Prinzhorn, Jean Dubuffet and Harald Szeemann, 2015

- David MacLagan, Outsider Art: From the Margins to the Marketplace, 2009

- John Maizels, Raw Creation: Outsider Art and Beyond, 1996

- Lucienne Peiry, Art Brut: The Origins of Outsider Art, 2006

Watch

Revisit a discussion between Sarah Lombardi, director of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne and Ben Platts-Mills, author and arts facilitator, about Martine Deyres’s documentary, Our Lucky Hours - the story of a pioneering psychiatric institution in 1930s France.

This talk took place live in March 2021, as part of our Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty free talks series.

Watch more talks including conversations with artists Rashid Johnson, Rose Wylie, Lindsey Mendick, Julie Mehretu, and Adam Green.